Since 2001, over 2,200 U.S. soldiers have been killed occupying the country, and nearly 18,000 have been wounded. By some estimates the war has cost over $645 billion, and the cost will continue to climb for decades after the last soldier is withdrawn. And none of this holds a candle, of course, to the suffering of ordinary Afghans, who have by now endured decades of war.

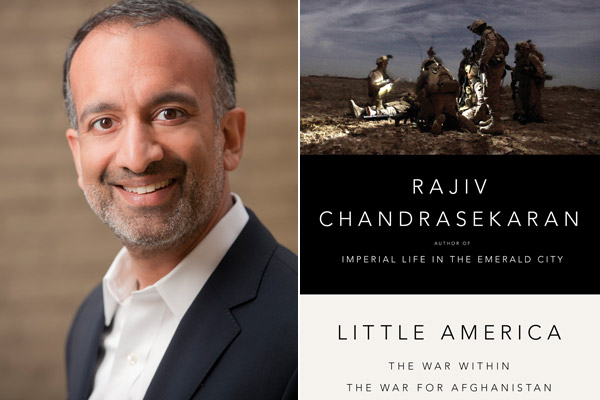

To veteran Washington Post reporter Rajiv Chandrasekaran, this all poses the question: was it worth it? Did each life lost, limb blown off, and dollar spent go toward making a better Afghanistan or a more secure United States?

That’s the question Chandrasekaran begins with, and returns to often, in his most recent book, Little America: The War within the War for Afghanistan. It’s a stirring survey of U.S. policy in Afghanistan—and the infighting surrounding it—since the 2009 troop surge.

He introduces the reader to Afghanistan through the story of Paul Jones, an engineer who was part of the American plan to bring modernization to Afghanistan. Jones found himself in what the Afghans had dubbed “Little America,” an attempted reproduction of suburban America complete with irrigation canals and western-style schools, hospitals, and factories. Unfortunately, these modern niceties never seemed to spread beyond the walls of the cushy U.S. compound. This story of big promises and investments but small accomplishments serves as an analogue for the war after the 2009 troop surge, as told by Chandrasekaran.

Although sympathetic to the effort, Chandrasekaran details how his disillusionment with the war grew as he became increasingly convinced that instead of an unsustainable troop surge, President Obama should have committed a smaller number of troops over a longer period. Afghanistan, he says, “was a marathon, not a sprint.” By the end, Chandrasekaran concludes that “the American bureaucracy had become America’s worst enemy.”

The struggles of the U.S. war effort, according to Chandrasekaran, can be attributed to policies as well as people, including generals, politicians, and bureaucrats. He critically examines the decisions to send Marines to the Helmand River Valley rather than the strategic district of Kandahar, to fund and then scrap projects to build roads and provide electricity, and to befriend some corrupt leaders like Ahmed Wali Karzai and work around others.

At the military level, Chandrasekaran observes, discord between different branches of the armed forces has contributed to operational failings as well as tension between U.S. and NATO forces. The Marines, for example, demanded independence from the Army in order to station themselves in districts of their own choosing, damaging their relationship with NATO troops already stationed there in the process.

At the bureaucratic level, Chandrasekaran criticizes Obama’s war cabinet for being “too often at war with itself,” a problem “compounded by stubbornness and incompetence at the State Department and USAID.” Lieut. Gen. Doug Lute, former ambassador to Afghanistan Karl Eikenberry, and the late Richard Holbrooke, a special adviser on Pakistan and Afghanistan, all receive praise from Chandrasekaran, but he points out over and over again they would have been able to accomplish so much more had they been focused on rebuilding Afghanistan and not outshining one another.

He also lambasts overreaching and underperforming development projects like USAID’s bid to build new power plants, an effort largely contracted out to non-governmental organizations that prioritize budget lists and deadlines over meaningful progress and hands-on involvement.

But for all the criticism that Chandrasekaran doles out, he also gives praise to the few he believes deserve it. Kael Weston, a State Department official with experience in Iraq and Afghanistan and an adviser to the top Marine commander in Afghanistan, is closest thing to a hero that this book offers. Weston believed that “Obama should have gone long, not big,” referring to the troop surge, for which Chandrasekaran lauds him as having “been right all along.” Chandrasekaran’s increasing skepticism towards the war is in direct correlation with Weston’s.

By the end of the book, Chandrasekaran is convinced that what Afghanistan needed from the United States was a president who was not afraid to stand up to his generals and forge a plan that was focused more on a partnership with the Afghan government and less on military force. Bringing in fewer troops over a longer period would have delegated more responsibility to the Afghan government and resulted in fewer Americans killed and dollars lost for something that just wasn’t worth it.

In the final pages, Chandrasekaran lays out the fundamental problems: “For all their talk about the importance of building an Afghan army, the American generals didn’t act on their words.” Pointing out the vast disconnect between U.S. forces and their purported Afghan partners, he adds, “Too few soldiers were ordered to leave their air-conditioned bases and live among the people. … Our uniformed and civilian bureaucracies were rife with internal rivalries and go-it-alone agenda. Our development experts were inept. Our leaders were distracted. For years we dwelled on the limitations of the Afghans. We should have focused on ours.”