Cross-posted from JohnFeffer.com.

In March 1990, just after the first and only democratic elections in East Germany, I visited the House of Democracy in East Berlin. In this building on Friedrichstrasse, at a prime location near Unter den Linden and the luxurious Grand Hotel, were located all of the major civic initiatives that had ushered democracy into the country. “Ushered” is the operative word here, for these groups did not play a prominent role in the ensuing drama of the elections. The primary coalition of these groups – Alliance 90 – received less than 3 percent of the vote. The Independent Women’s Association (UFV) teamed up with the Green Party and captured only 2 percent, which translated into eight seats in the parliament.

When I talked to Petra Wunderlich of the UFV on that day in March in 1990, she was not happy about the electoral turnout or the fact that the Green Party alliance partner had grabbed all eight parliamentary seats. Under East Germany’s Communist-era constitution, women enjoyed the same rights as men. Childcare was widely available, and abortion was not restricted. But the society remained traditionally patriarchal in many respects. It was hard not to see the marginalizing of the UFV in this context.

Twenty-three years later, the House of Democracy has moved to another part of Berlin and changed its name to the House of Democracy and Human Rights. It’s a large building with a tremendous variety of civic associations including the Tibet Initiative, the Bangladesh Forum, and the Anti-Discrimination Bureau. The UFV is no more, and I couldn’t track down Petra Wunderlich. Even her former colleagues were not sure where she was, though they thought that she’d perhaps left for western Germany.

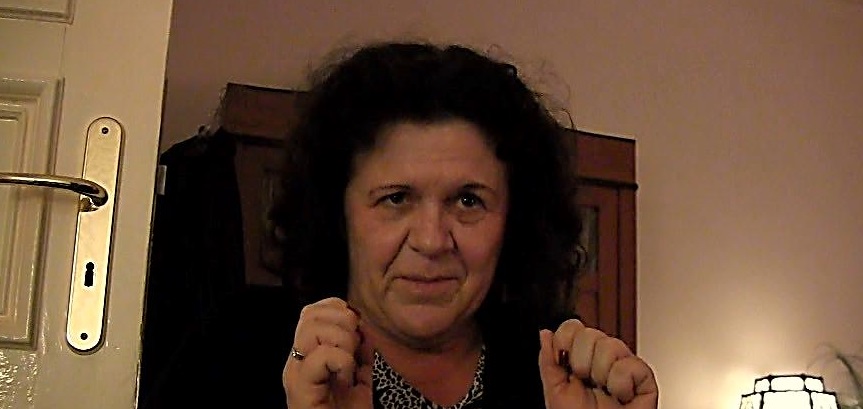

But I did have a chance to interview Tatjana Bohm, a founding member of the UFV who participated in the Round Table, where she co-authored the social charter, and served as a minister without portfolio in the second government of Hans Modrow. For the last two decades, she has worked in the Brandenburg regional government in the ministry of labor, social affairs, health, and women.

The major group inside Alliance 90 – Neues Forum – was not interested in the message of the UFV, Bohm remembered. But other influential activists were determined to ensure that she participated in the Round Table. “Our demands were not like the feminist demands in the West,” she told me. “We were not that radical. I, myself, would have been more radical, but here it was about social rights – we were all still very socialist during this autumn – and those social rights were legitimate. These social rights, like the protection of child welfare institutions, quotas, unemployment benefits, many of these have again become mainstream issues. It was all about equal rights for equal qualifications.”

It was not an easy fight – during either that brief democratic period in East Germany or in the new reunified Germany. Bohm relishes a good fight, however. “There is this saying: ‘If you don’t fight back, if you don’t resist, you will end up in the kitchen.’ By saying this we could acquire greater legitimacy for our movement: if we don’t do something now, we will lose in this process. It was also about improving childcare institutions, not closing them. It was about getting rid of the ideology within those institutions. And then when things were going really fast, there was also one issue everybody agreed on: to keep abortion rights. A big majority was in favor of keeping the provisions in East Germany.”

Childcare centers closed. A more restrictive abortion eventually went into effect (legal in the first trimester but only with counseling and not covered by public health insurance except for low-income women). But the government of Angela Merkel – one of the founding members of the East German group Democratic Awakening, which aligned with the Christian Democratic party in the 1990 elections – has revived at least one of the features of the old East German system: guaranteed childcare.

For Bohm, it is a confirmation of what she’s been saying along. “Yesterday, I was reading in the magazine Der Spiegel about the ‘German family policy,’” she related. “This is just what I’ve been saying for the last 20 years: exactly the same arguments. It seems we had to wait for such a long time before it became a public debate. The current policy includes spousal joint tax declaration and other incentives. This is what we’ve been telling them for 20 years. And finally we have a discussion about sexism, about victimization, about rape. Women are talking now. For the first time ever in Germany we have a debate about the relationship between the sexes and especially concerning the workplace, all those things that happen daily and people just say: ‘Oh, don’t take it seriously, it is not so bad after all.’”

The Interview

Do you remember where you were and what you were thinking when you heard about the fall of the Berlin Wall?

I was in this exact room. I still had a TV over there. And I was writing papers. Back then we were always writing papers for the Women’s Association. So I was sitting there, writing down some ideas and then I saw the press conference on television. I saw it live.

And what did you do?

I said: Fine, be that as it may. And then I continued my work, which was more important for me.

When did the idea of the Independent Women’s Association happen?

It was during the early autumn. There were several different groups of women: scientists, the Lila Offensive (“Purple Offensive”), Women in the Church. And our idea was that these different groups should work together. So those groups joined as one group – on the basis of who-knows-whom and who-has-already-discussed-with-whom – in September. Neues Forum had already been founded, so this was also the time when the Bürgerbewegung became organized. There was the idea that this women’s association, a civil movement, a grass roots movement should be founded on the basic foundation of women’s rights and women’s democracy: everything that concerned women.

And so you were preparing those materials on November 9?

Yes, while I was watching the press conference I was working on materials concerning questions of equality. It was Thursday in the evening. Friday I had to go to work again. Of course I saw everyone coming back on Friday in the morning. On Friday evening I also went together with my daughter and a friend. We used the crossing point at Checkpoint Charlie. We went over to see friends in West Berlin. And just when Willy Brandt and all the others arrived, we crossed the border and went to the Town Hall of Schöneberg. They all were there, singing out of tune. After that I went to my friends’ place in West Berlin. I did not return until Sunday. This second night, Friday night at the Kuhdamm, with all the people there, this whole atmosphere in West Berlin was very euphoric because the border was open and we couldn’t believe it. It was realistic as well as unrealistic at the same time … amazing!

When you came back on Sunday, did you still have this euphoria?

The euphoria was there the whole time. We did not know everything that was happening. At the end of October the danger that it would not remain peaceful had somehow passed. It was about acting then, about doing something. The euphoria to change something was even bigger for me than the euphoria about meeting my friends in West Berlin.

How did you think die Wende would affect women? Especially here in the East, in GDR?

First of all there was our message: You cannot make a state without women. This message was due to the fact that we were also academics: sociologists, philosophers, and so on. Women were active in all the groups, including those groups that didn’t specifically deal with women’s issues. Actually if you go through such a process women will create their own issues: this had been clear to us before. Such fundamental changes within a society always carry the danger that women are marginalized or that their situation deteriorates. This was the reason why we organized ourselves as a separate association of groups to focus on women’s issues, and we organized neither as a party nor a movement.

What kind of reaction did you get from groups like Neues Forum and the Greens, from the Bürgerbewegung?

Neues Forum was not interested at all. We received support for our issues from IFM (Initiative for Peace and Human Rights), from people like Reinhard Weißhuhn. Wolfgang Ullmann, who was a very important person in Demokratie Jetzt and at the Round Table, also supported us very much so that we could join the Round Table. Also Ibrahim Böhme and Gerd Poppe, important people who had been in the opposition for a long time. They supported us to participate in the Round Table.

When I talked with Petra Wunderlich 23 years ago, she used the German word Emanzen to describe a negative perception of the Independent Women’s Association as too feminist.

To me it is more a term of honor. The terms “women’s rights” and “emancipation of women” were not perceived as bad back then as they are perceived today. I would disagree with Petra on this. Our demands were not like the feminist demands in the West. We were not that radical. I, myself, would have been more radical, but here it was about social rights – we were all still very socialist during this autumn – and those social rights were legitimate. These social rights, like the protection of child welfare institutions, quotas, unemployment benefits, many of these have again become mainstream issues. It was all about equal rights for equal qualifications. Back then women here were highly qualified, just like it is nowadays for the new generation. As we grew older we realized that in the GDR to get higher professional positions, you had to meet criteria based on political attitudes as well as on gender. If you didn’t meet those criteria, you were excluded. The GDR society was a very paternalistic society.

There is this saying: “If you don’t fight back, if you don’t resist, you will end up in the kitchen.” By saying this we could acquire greater legitimacy for our movement: if we don’t do something now, we will lose in this process. It was also about improving childcare institutions, not closing them. It was about getting rid of the ideology within those institutions. And then when things were going really fast, there was also one issue everybody agreed on: to keep abortion rights. A big majority was in favor of keeping the provisions in East Germany.

During the Round Table discussion, do you feel that you as a movement were successful in raising the concerns of women and getting the government to hear you?

Yes.

Can you give me examples?

This happened during such a short time. This is the difference between us and the rest of Eastern Europe. We had to talk about women issues at the Round Table. We had to discuss schools, kindergartens, social policy, health issues. Today in Germany you cannot imagine how seriously women issues were discussed back then. And of course we were also clever. And charming.

The moderators from the Church – with the exception of the Catholic moderator — were not able to really communicate with us at the beginning. But in the end they really loved us, because of our charm and how we did not aggravate situations. The Round Table had a number of groups that worked on different issues. There was also a sub-working group on women and gender equality. But I worked in the group on the constitution and on human rights issues. I worked on the drafts of the constitution. Within this whole discussion about the constitution we treated the issue of women’s rights and democracy in a very good, very modern way. It was a really big question about how women’s issues and democracy came together. And because I knew very well how to deal with it, the atmosphere was totally different compared to later parliaments.

In general terms we made great progress with these drafts, especially when it came to human rights. The point was that human rights are women’s rights and women’s rights are human rights – it goes both ways. Article 3 was partially adopted, with small changes, and it made its way into the Grundgesetz. It was not only about preserving rights that existed before 1989. It was also about further development, about the possibility not only to elect parties but create new structures with the participation of citizens. But almost nobody remembers this today. Because of the fall of the Wall, it just happened that other things played a much bigger role, like the offer of the D-Mark, which made things complicated. And, of course, the old things: the debate about the Stasi, the SED. The economy deteriorated.

Then there was this offer to “find shelter” within the Federal Republic even though we had a big movement rejecting Article 23, which was reunification through accession. We also had Article 146 that mandated a new constitution for Germany in the case of reunification. It turned out – and this is where we were wrong – that the majority wanted something else. The final unification agreement stated that all the laws and all the structures of the Federal Republic are valid.

When I was here – and talking to Petra – she mentioned how disappointed the Association was because there was some infighting, there was some struggle within the Bürgerbewegung and how you didn’t get any representation in parliament.

Yes and no. Yes, there was a struggle in the House of Democracy. There was an election involving the coordination board, and this was … terrible. But as I also was a minister at that time, there were other things I had to do, so I was only around sometimes. Besides I was the best when it came to mediate with theBürgerbewegungen.

Anyway, nobody thought that the election would have this outcome. We were together with the Green Party. There were the others: Neues Forum, IFM, and Democracy Now. They went together, but without us. The women did not want it. They thought the others were too patriarchal. I had a different opinion, but it doesn’t matter anymore. In the eyes of the women they were not feminist enough. In terms of realpolitik, it was a mistake. We made a lot of mistakes. Also all the civil movements expected to get more votes. It was an illusion. The SPD had this same illusion. It was a totally wrong assessment of the real situation – not in Berlin but in other parts of the former GDR.

We went together with the Greens. The electoral districts were the same as the former districts of the GDR. The first candidate was always the Green candidate, then we followed as second on the list. This was also a mistake. We thought: “Second position is fine, and we will enter parliament.” But only the Greens won. Then we were fighting to see if some of them would withdraw. I was running for office in the town of Karl-Marx-Stadt — in the second position. I had more votes than Matthias Platzeck, who was in the first position in Potsdam. But I was in a different electoral district, so I did not succeed. Since then I have had this incredible connection with Wolfgang Templin. We were the celebrities that lost all the elections.

So then we fell out with the Greens and with the civil movements. I have worked with them very closely on the Round Table concerning certain issues, and I continued to work with them in the parliamentary fraction, with people like Reinhard Weißhuhn. One part of the women’s movement did not want to continue this cooperation. Another part joined the reformed Socialists. We were all very socialist back then — except Joachim Gauck. In some things he is a honorable man, but no feminist ever would have voted for him considering his views on women. To him women’s issues are as far away as the moon or even further.

In the end, did you get representation in the Volkskammer?

No. We had no representation in the Volkskammer.

How long did the Association last? Because you said that many members went off to the PDS and they were unhappy about realpolitik. Was that the end of the association?

No. A part of the activists also joined the SPD. I went to Bündnis 90/Die Grünen. The association continued to exist for some more years until the middle of the 1990s. But we had to make this decision to join political parties. It was a question of power and realpolitik and people had different opinions on this. Plus, you had to continue to earn money. You had to pay rent. Somehow you had to leave the exhilaration of revolution and go back to daily life. Besides, everything changed so much after die Wende. Many tried to just work on real problems. For instance, we were totally successful in that the unification treaty included a special arrangement concerning paragraph 218 and the preservation of abortion rights. It lasted for two years. After that, the supreme court reversed this special arrangement. There were large demonstrations against this.

Women were also very active concerning certain social rights involving the transition. It was about the generation of the elders, those who were more than 50 years old. When all the enterprises were closed, a very good transition arrangement was found in comparison to my generation. Those between the ages of 30 and 40 have been the losers of die Wende in economic terms.

They were the losers because they lost their jobs and social benefits?

Well, especially for people like me who were well qualified. It was an exchange of elites of those born between 1955 and 1965. So many academic positions were emptied out because they evaluated what we had done. Friends of mine who had studied very interesting subjects during GDR times had to leave. Or they went to the West immediately. Those who had been a critical mass in the GDR lost a lot of social benefits.

If you were lucky, you went to the West, or you were able to adapt. In the academy of science, those who were well adapted and were really doing things found jobs or consultancies. But those people who really wanted to change something, many of them, well, they have been receiving Harz 4 [minimum social benefits] or some other nonsense for years. This is a very interesting topic from a sociological point of view. The children of former party functionaries – and it was even worse in the Soviet Union – used their old connections to get places in the new economy. It wasn’t only the nomenklatura. It was also those in the second or third rank, those who knew how the nomenklatura works and accordingly could watch closely in order to adapt later on, who knew that the world has changed and this is how it works now. But those who really wanted to change something…. If you know something about revolutions this would be clear, but when you are experiencing it in reality it’s still bitter.

I am working now in the government in Potsdam. Today they would not have hired somebody like me. There were many from the second and third rank from the former state apparatus who were brought in. And those are the ones who have this incredible ability to adapt. They knew how administration and bureaucracy works and the rules of the game.

Before 1989, when did you first become politicized on women’s issues? When did you first consider yourself a feminist?

I am a natural feminist.

From the day you were born?

I think so! I am a troublemaker. I always took seriously the things that were said about women’s rights during GDR time. I was strong-willed. I was a very good student in school: very lazy but intelligent and quite funny. I would describe my family as post-war functionaries. There is a communist-socialist part to my family and, on the side of my grandmother, a bourgeois part. My mother was very well qualified. She always earned more money than my father. I grew up in a strange extended family in the midst of several generations of women. These women were totally equal and in charge. For me, this was a natural situation. My grandfather, for example, cared for my grandmother for 20 years.

During a cleanup in the SED, my mother came to the state women’s organization. She was a functionary there. This was my childhood. The Democratic Women’s Association, where my mother worked, was a mass organization. Of course I joined my mother when she was going around the country. She was agitating for a kindergarten or some other improvement for women carrying a double burden or arguing that women in the Erzgebirge region should have a job. I thought all of this was totally fine. Also that she took her job so seriously. I had a very strong mother. She was not that close to me, but she had these very clear principles.

Then I finished school. I did the A-Levels and went to Berlin. There you were often discriminated against because you were a women. And you felt bad, wondering why they were treating you like that. This affected me a lot. This is why I say that I am a genuine feminist. If you studied in Berlin and you were a person like me, then you got to know people from West Berlin. I read all the important books at the end of the 1970s and during the 1980s: Doris Lessing, Betty Friedan, Anja Meulenbelt, Shulamith Firestone. They smuggled them through for me. This influenced me politically. I also studied philosophy and sociology.

Was there a point at which you crossed the line politically during the GDR days into political action?

This is difficult because last year I read my Stasi file, and I don’t want to mix it up with how they interpreted it. It was difficult for me because I never wanted to read it ever but finally I had to read it. There were moments in 1983-84 when we had some trouble at the Academy of Science concerning issues like demography, the issue of “whether women should have more children.” This was such an ideological moment when the paternalism became so strong and yet was accepted by women, that they should have jobs and also have more children. Back then I had strong positions on these issues. At the same time the Stasi demanded my files and life became difficult for me. I did not have to go to prison, but they tried to make my life difficult. All sociological research had to be approved by the Politburo. Sometimes this was more strict, sometimes less. But I had troubles since I was not sufficiently well adapted to the scientific questions.

The second point was Gorbachev and more precisely glasnost (and not so much perestroika). And of course during the 1980s, in addition to the feminist books, I read everything about the Soviet Union and about Stalinism as well as Eugen Kogon’s Der SS-Staat (The SS-state). The first sociological empirical study of the concentration camps was published in 1948. I got all these books from my friends from West Berlin and in this way I was saying goodbye to socialism. So, during the 1990s I had no problem because I had already cried and suffered for the idea or the betrayal of the idea during the 1980s.

When I was 17 years old I’d already read a book in the basement of my parents: Protokolle über die Slánský Prozesse (Transcripts of the Slánský trials) about the Slánský trials in Prague. Show trials took place in all the European countries except for the GDR. This book was published in the GDR. Also I had a school friend who belonged to that generation of German Communists who were part of the Volga German community, which had been in the Soviet Union and returned from the camps only in 1959. Her father had One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, the first and best book of Solzhenitsyn, which we also read.

So you waited a long time to look into your file. Why did you wait so long?

Because I knew the basic issues, and I did not want to know the details. The police files don’t tell the whole story. If there hadn’t been this really stupid incident, which still has to be investigated, I would not have looked at all. It happened last year, and it really affected me. I had to read my file to defend myself. The Gauck office provided some information that was somehow not clear – later they took everything back. But still, now I am clearly a victim. So I had to read all of it. They made a real error. I’ve talked to my boss about how this could have happened. The worst thing was my helplessness.

During the Communist period, there were some idiots here in this house who wrote things about me. It was not so much about my activities in oppositional circles but simply because I was different, because I lived differently, in a more liberal way. They said I was a bad mother. They could have taken my child away. Everything was prepared. My mail was monitored until October 1989. And I had to justify myself in front of these idiots in Potsdam. What they did was more than … it was terrible. I thought that I had managed to successfully overcome everything in the GDR. I was always active. But in this new system, just because they somehow made a mistake, I had to justify myself. They invaded my life like they invaded others before. And I’ve suffered collateral damage that goes deep into my private well being after 23 years. It really hurt me.

Unexpectedly.

Yes.

What was the motivation of these “idiots in Potsdam”?

To protect the government of the Brandenburg district: to protect ministers, to protect the prime minister, to avoid bad headlines in the newspapers. Just like they had done at the time of Manfred Stolpe. They made mistakes when hiring employees, but they couldn’t admit that they’d made mistakes. So the bureaucracy protected itself at the expense of other people.

And so they made an accusation?

It did not go that far. But I was subject to their whims. I still have to decide whether I want to initiate legal steps. On the other hand I would not achieve anything by that. I am really in a totally stupid position. The Gauck office has made really big mistakes. Maybe somebody there did not like feminists. But now, if I start a legal process, I would prove those trivializers right, the ones who always say: “Yes, we’ve always known this. The Gauck office is doing that only to kick people out of their jobs. The Gauck office forged files and did wrong things, exactly like the Stasi did.” It would also give a free pass to the real Stasi officers and employees.

So this is a situation you’re currently in?

It happened last year. I’m still a little bit emotional about it. I was so helpless. I’ve been reading about it and laughing about it. And then it was as if something opened up, all the conflicting emotions locked up inside of me. I am very well able to forgive and to be indulgent. But now I understand why some people have become so bitter. But I had other things to deal with. I have a foster child upstairs. I was lucky because I got out of this situation. But it unsettled me fundamentally.

So what is the situation now?

I took a break. And two weeks ago I spoke with Roland Jahn [the head of the bureau in charge of the Stasi files] to see how this information evolved. I want them to investigate now. I am still waiting for some other files. But now I’ve got to the point when I am going to write again to Roland Jahn so that they investigate and see how this information was released.

The information only came out within the ministry? Or did it come out in public as well?

Only in the ministry. In public it would have been better. But I did not do it. They always told me: “If this came out in public it would be very bad.” It would not have been bad from my point of view. They always said: “It will be terrible for you.” Nonsense. Actually, and this is somehow the crazy part: I do not agree with the Stasi law and how it is today, that people can continue to make these inquiries. Actually I take the other position: of forgiveness and of putting issues in the right perspective. This means understanding that people were young. I don’t like the way in which it is done today. But I want to investigate it.

Do you know about other people in a similar situation?

No. It’s a very special situation.

I was surprised to discover that there are still issues with the Stasi files here in Germany. In other countries in the region, the investigations are usually only for politicians. For everybody else, the issue is closed.

Actually I do agree. Issues like that should come to an end finally.

It’s important though because I think it’s very difficult for people outside of Germany to understand this issue. So your case is an important case. I know it’s painful.

I know: everywhere it’s like this. I did not want any of this, and somehow I am a bit hurt that it affected me in this way. I am not bitter. And I don’t have a lifetime to listen to why traitors have done their betrayal. But now I can better understand people who are bitter. I want to deal with other things now. I want to have the energy to do other work.

I did want to ask you about the work you are doing, so I apologize for bringing up these other issues. So, you work today in Brandenburg, in Potsdam, in the ministry on social policy?

On women issues.

So this is a great continuity.

Yes.

When did you start that work?

I could have gone to Harvard to join the Center for European Studies for half a year. This was after I was not elected during the elections for the Bundestag. I ran for office in the West and the Greens did not get in. After that I had my daughter. I’d traveled relatively often to the United States to join scholars’ conferences, and I quite liked Harvard. They would have liked me to join them for half a year, but I also had to look for a job because I had a young daughter I had to care for.

That’s why I took the job in Potsdam. I was at the end of my political career, but I was more interested in the issues. And I have to say, also because of political issues, my science career in the GDR did not go well. Professors from the West later offered for me to do a PhD with them on social politics – because I’d also written a social charter. But I said that I wouldn’t do that. I didn’t have to do this anymore. I was able to give presentations in Harvard, that was enough. So I looked for the job in Brandenburg. I took the job at the ministry in 1992.

So you’ve been there more than 20 years? That’s fabulous.

First I was working there on family policy and women. And for 10 years now I’ve worked on all the interesting topics. I still do reproductive rights as well as trafficking, prostitution, and violence against women. You have to do a lot to prevent the situation from deteriorating. I was one of the last standing against the backlash. Young women don’t realize that when abortion rights are slightly changed it becomes more difficult for them. I am very liberal, which means I think that the state should not get involved in certain things. I still like the work; I’m still interested in the topics. I still have fun at work. Not everyday of course, sometime it is just terrible. But I am not frustrated.

Now things are changing. It’s something that I’ve long hoped for. Yesterday, I was reading in the magazine Der Spiegel about the “German family policy.” This is just what I’ve been saying for the last 20 years: exactly the same arguments. It seems we had to wait for such a long time before it became a public debate. The current policy includes spousal joint tax declaration and other incentives. This is what we’ve been telling them for 20 years. And finally we have a discussion about sexism, about victimization, about rape. Women are talking now. For the first time ever in Germany we have a debate about the relationship between the sexes and especially concerning the workplace, all those things that happen daily and people just say: “Oh, don’t take it seriously, it is not so bad after all.” Now we are looking for the best strategies to fight back.

I don’t want to penalize people. I want to change civil culture. There are always excuses for domestic violence, everything to absolve the perpetrator. When I am in New York or in Boston I’ve always felt better. And then when I come back I say: I’ve returned to the Stone Age. There’s a lot of minimization that takes place here. Women are put in situations where they feel uncomfortable, where they don’t have anyone to talk to. I’m not talking about cases of crime. I’m talking here about uncomfortable situations. And then they hear, just like during GDR times: “Don’t make such a fuss. It is not so bad. There are much worse things.”

I am sorry that you have to have this debate in Germany.

It’s good! It’s necessary.

I mean: I’m sorry you have the phenomenon that requires the debate. The debate is good.

Yes, it is. And until now we’ve always suppressed it.

What do you think were the major accomplishments in your job in the ministry? And what do you think have been major accomplishments for women here in Germany? I know that there are still problems, but what has improved over the last 20 years?

What has improved? I’m very, very ambivalent. There are accomplishments – but you should not compare it to Scandinavia. Certain issues have always been obvious to me personally: to have a job, to be independent, to live a free life. Okay, this concerns mostly middle-class women, but certain possibilities exist. It’s exhausting to struggle against the paternalistic system – be it the state, be it the church. And naturally there are backlashes. But the future tendency is: women as human beings, as working, thinking creatures, as citizens.

Nobody has been researched like the woman in the East. In the 1990s we had a nice saying: “The phenomenon of the Eastern woman.” Here in East Germany, there was an almost incomprehensible “affinity” for work. East German women possess an “affinity for work” that is still unbroken. All the studies in the 1990s show this. We don’t understand why this “affinity” is unbroken — as if the necessity to pay your rent is an affinity like loving yellow or red curtains. Women like to go to work every day, even if it is uninteresting work. It’s not only work for self-fulfillment. And now they say that the German economy, in order to survive in the international competition with China, needs working women. It is like during GDR times!

We have disappeared as a subject. Now I’m starting to talk sociologically again. We are “evaluated.” It used to be by the Stasi. Now it’s only the Western people who are evaluating, mostly the West German man but sometimes also the West German woman. The East German civil movement — East German citizens as an independent subject — has disappeared. The Western parties, the Western enterprises… they labeled us. There is no reflection about this. But such reflection is necessary for the German society. It’s necessary also for Europe.

So, this is a major frustration that West German men are the subjects and the people here in the East are not subjects. But they were subjects.

Yes. For a short time. And they have done real wonderful things.

And that’s frustrating.

Not so much for me. But I can see that it’s frustrating for many people.

When you reflect back to 1989 and what you were thinking back then, your Weltanschauung, has anything changed for you personally?

Yes. The value of being friendly with your neighbor. In America I’ve learned that people have a differentWeltanschauung. With them you have to find points of common interest and then you can communicate. You can have a separate Weltanschauung without having to convince the other person or try to force them to accept yours. I learned a lot about democracy and the culture of discussion in the United States. I’m not talking about the war in Iraq right now but about the things I still like in the United States. I took my parents, who were nice people but old Stalinists, to America. They were able to communicate with ordinary people there and eradicate the concept of the enemy.

I’ve also learned how fragile our civilization is. I think that we in the West do many things in the wrong way. Just think about the Arab Spring. Who has been to these countries? Who has read their stories? In Afghanistan, the Americans and the Germans are experiencing the same thing the Russians did before — only we have better weapons.

Well, this is not the way. We have to strengthen our democracy. We have to settle the social question in our countries. We have to be much, much more generous. Capitalism must not be omnipresent in every sphere of life. We don’t have empathy for poor people anymore. Our societies are closing — not only to the outside but also on the inside. We don’t have understanding anymore for poor people that live differently from what we would deem a good life. They barely have a chance anymore. Before the children of the middle-class are even born they are already preparing in utero for life’s competition. This is crazy. This is how we lose our quality of life. What is the good life? The richest countries, and especially Germany, have to ask this question.

It is also through conversations like this that I can realize what I too actually want in life. I have a secure life. My daughter has a good education, a good job. We care for the foster child. I do many important things, which are much more important than running for a seat in parliament. But such conversations make me reflect on various issues, see the connections rather than be bitter.

It was a great opening for me to go to the United States. When it was so bad last year concerning the Stasi file – it started in March and continued until August – I went to the United States in September. I’d made a similar journey in 1990 on my first speaking tour in America: New England and Washington, DC. This time I visited Nanette Funk in New York. Then I went to Rhode Island where my ex-husband lives. Then I went to Boston, where I became friends with a secretary from Harvard with whom I am still friends after 20 years. And this healed me: simply to be there. I didn’t shop, nor did I go to museums. I simply visited New England in fall. It had an incredible healing effect: simply to be there.

I have three last quantitative questions. When you look from 1989 to today at everything that has changed or not changed, how do you evaluate that process here in Germany on a scale of 1 to 10 with 1 being least satisfied and 10 being most satisfied?

For Germany I say 5.

And personally?

Personally I choose 7.

And then if you look in the future, how do you evaluate the prospects for Germany over the next two to three years on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 being most pessimistic and 10 being most optimistic?

Actually I’d have to say 2 as well as 7. Things could become really bad with the Euro-crisis. Society could become more and more closed. But it also has the chance to open up. That’s why 5 would not be right. I want to stress this ambivalence. It is both: 2 and 7. But it is not 5.

Berlin, February 5, 2013

Interpreter: Sarah Bohm

Interview (1990)

The party that far and away had the best posters in the March elections was the coalition between the Greens and the Independent Women’s Association (UFV). While the coalition seemed to work well artistically, the post-election relationship has deteriorated. The coalition only placed 8 representatives in the parliament and by a complicated procedure, the Greens have denied their partner in the coalition any of those seats! Originally, the electoral spots were determined nationally and the UFV was given spots 3, 5 and 8–in other words, if the coalition won 6 seats in parliament, the UFV would get two reps in the third and fifth position. But then, the election rules changed and representation was switched to local and the UFV was then given spots 2, 5 and 8. The problem is, the coalition never received sufficient votes in any region to send two candidates to the Volkskammer. The eight spots that they eventually won came from eight different regions.

Negotiations between the two groups have stretched along for some time but the Green leadership won’t budge–it refuses to allow the UFV any representation in Parliament. The Greens say: two of our eight Green reps are women, isn’t that enough? They also say that all eight spots are needed to push for environmental issues. But, counters the UFV, we were in a coalition–so obviously any UFV reps would defend environmental issues just as strenuously as Green reps. But it doesn’t look as though the Greens will give any ground.

It was in this context that I met with Petra Wunderlich and talked about the women’s movement in the GDR. She was understandably a little pessimistic, given the coalitional fiasco. She first provided a little history to the movement.

In 1949, the German Democratic Women’s Association was formed (DBD) but was quickly absorbed into the SED sphere. It was, in these days, family-oriented rather than feminist. There wasn’t much independent activity until the 1980s when the group Women for Peace was formed. By 1989, various groups around the country were talking about an alliance and on December 3, 1989, the Independent Women’s Association was formed. At that time, the major issue was getting women’s issues and representatives of such positions into the round table which, after some struggle, was accomplished. Then on February 17, at a founding Congress, it was officially registered to participate in the elections. Meanwhile, the elections were being changed from May to March and there was very little time to organize an autonomous campaign. Further, there was the problem of coordinating women of very different political perspectives.

But in order to understand why they eventually aligned with the Greens, it is necessary to go back to December when all the various left-leaning groups met to form an alliance. No consensus could be reached at the time. By January, various pairings were tentatively being explored, but once again consensus was difficult and personality and ideology were splitting Greens from United Left and so on. There seemed to be one point of general agreement however: the UFV was too radical. In Bundnis 90, it was Democracy Now, with its close church connections, which made it impossible for an expanded coalition with the Women. Only the Greens and the UFV could find enough agreement to form a tie. Why did the other groups consider the UFV too radical? They were considered “emanzen” which is a pejorative German word for feminist, derived from emancipation. Wunderlich gave an example. When the UFV called for a Ministry for Equal Opportunity, many people in the opposition said that legally, according to the East German constitution, women were equal to men. So what did women then want, they asked? The emanzen wanted superiority was the answer. Nevertheless, the round table approved this not terribly radical resolution.

In addition to this resolution, the UFV wants to promote the economic independence of women. Previously the government encouraged both marriage and child-rearing through favorable subsidies and preferential access to apartments and so on. Loans were offered interest-free for married couples under the age of 25. This policy encouraged early marriages, frequent children and then, after the money ran out, early divorce. The UFV wants to encourage discussion on these issues, especially among young women.

While the UFV is now being forced to concentrate its activities outside Parliament, it is also looking for someone inside the Volkskammer who could represent its interests. It is also continuing to coordinate activities among women’s groups around the country, promoting the idea “from women for women.” It is also starting to work with unions. But it is also becoming increasingly clear that the UFV is committed to left issues and can therefore no longer represent the views of women on the right.