The Obama administration’s redefined military mission in Afghanistan has dramatically increased pressure on the Afghan government to demonstrate it can provide for its citizens without U.S. assistance. Yet despite billions of dollars spent on military and civilian efforts, eight years of nation-building haven’t yielded adequate results.

The Obama administration’s redefined military mission in Afghanistan has dramatically increased pressure on the Afghan government to demonstrate it can provide for its citizens without U.S. assistance. Yet despite billions of dollars spent on military and civilian efforts, eight years of nation-building haven’t yielded adequate results.

The gap between expectations and results on the nation-building front should come as no surprise, given the impossible standards by which these results are being measured. Creating large-scale economic growth and good governance in underdeveloped countries are time-consuming endeavors in the safest of working environments. In countries without basic security, they’re extreme challenges.

It Takes a Community

The term “nation-building” implies the transformation of an entire system that even in the smallest countries would be unrealistic. Systemic changes cannot provide immediate tangible benefits to an entire population. Community building, however, is a much more realistic goal. In the development lexicon, community development often refers to creating or enhancing the state structure or the public sector’s capacity to deliver services.

Community development can be seen as nation-building writ small. As a microcosm of nation-building, small communities in countries such as Bolivia, Botswana, and Indonesia have grown stronger and more coherent, as farmers’ associations, cell-phone entrepreneurs, and independent journalists help establish and sustain social roots by developing local markets and media, with international donor assistance. The economic benefits are also significant. For example, with assistance from USAID, farmers in the Bolivian region of Oruro began exporting organic sweet onions to a specialty vegetable buyer in Los Angeles, who in turn stocks supermarket shelves across the United States during the winter, when such crops don’t grow domestically.

The methodology that produced these success stories in traditional development environments — i.e., countries at peace — increasingly applies to countries that have been recently affected by conflict or are still in the midst of conflict. In parts of Southern Sudan, where internally displaced people returned to towns that had little or no remaining infrastructure, U.S. assistance enabled an independent microfinance institution to open five branches that offered capital to more than 6,000 clients to launch their own micro-businesses.

The Challenge of Afghanistan

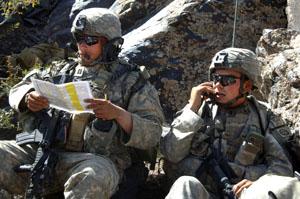

Afghanistan, however, requires a greater level of physical security than the average development project. To address this threat, the U.S. government is using Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) staffed by both military and civilian planners. But this tactic can have the unintended consequence of blurring the line between military engagement and development assistance.

While PRTs make sense logistically and practically — providing development practitioners with access to areas where only the military can reach — the fuzziness between military and civilian engagement is problematic on two levels. At the local level, the trust that development professionals gain by working with Afghan professionals and beneficiaries can erode when they’re seen as an extension of the military. Likewise, including development success as a factor in “winning the war” can create an impression among congressional overseers that military success and development can be measured according to the same standards.

For the military, removing the enemy and providing a secure environment that enables a provincial government to deliver basic services is a short-term win that elicits further funding to replicate that success elsewhere. Economic growth, however, cannot be measured in terms of immediate impact. Results take time. For example, over the past four years traditional business practices have been used to strengthen commercial agribusiness value chains in the Helmand and Kandahar provinces. U.S. foreign assistance in those areas has led to $43.4 million in domestic wheat sales and $28.2 million in export sales of fruits, nuts, and vegetables. More recently, assistance to the poultry industry in Helmand has generated more than $900,000 in sales of poultry, feed, and livestock, creating local jobs and reducing the dependency on imports from India, Pakistan, and Iran.

The economic model that generated these sales required time to be effective and convince occasionally competing interests that collaborative work could lead to better collective results. Often by the time positive results are achieved, unlike in a military campaign, circumstances have changed so much that only disciplined monitoring and evaluation can demonstrate the value of the U.S. government’s original contribution. And those evaluations make news only when they turn up waste or abuse.

The economic model that generated these sales required time to be effective and convince occasionally competing interests that collaborative work could lead to better collective results. Often by the time positive results are achieved, unlike in a military campaign, circumstances have changed so much that only disciplined monitoring and evaluation can demonstrate the value of the U.S. government’s original contribution. And those evaluations make news only when they turn up waste or abuse.

New Problems, New Tools

Far from discouraging development assistance, such success stories have created a sense in many corners of the international development community that pockets of opportunity exist in conflict-affected countries. To address the specific challenges of working in these environments, USAID created an office of Conflict Management and Mitigation. This office, along with other tools and resources, demonstrates the commitment the development community is making to bring traditional economic growth and education opportunities to populations who don’t have the luxury of longer-term personal and communal planning.

Examples of supposed waste and abuse of funds distributed by international donors in the most challenging circumstances — lawless environments where war is still a daily reality — are often a snapshot in time. By definition, development is a long-term process. The current generation of policymakers isn’t the first to have little patience in demanding immediate impact from taxpayer dollars spent overseas. But increasingly, development projects are expected to solve the problems not only of historically inoperable states but also of those recently destroyed by war in equally short order. Advanced tools of warfare have greatly expedited our ability to project power. But the success of rebuilding a community, never mind a nation, should not be judged according to a military timeline.