With the possible exception of Ted Cruz, who proposed that the U.S. carpet-bomb Syria, discussion of foreign policy has been notably absent from the pre-primary election campaigns of both parties. Consequently we can only hope that the next president will have the temperament to rely on diplomatic solutions rather hasty military action. It is an issue that could determine the fate of America and much of the world.

In 2008 voters elected Barack Obama with high hopes that he would not commit the same sins as George W. Bush by lying to the American people, taking the country into needless wars, and ignoring international law and the U.S. Constitution. He has disappointed many of those hopes. He expanded the war in Afghanistan after saying he was ending it, he continued to hold dozens of prisoners in Guantanamo, and he authorized drone strikes and the assassination of suspected terrorists, in countries with which we were not at war.

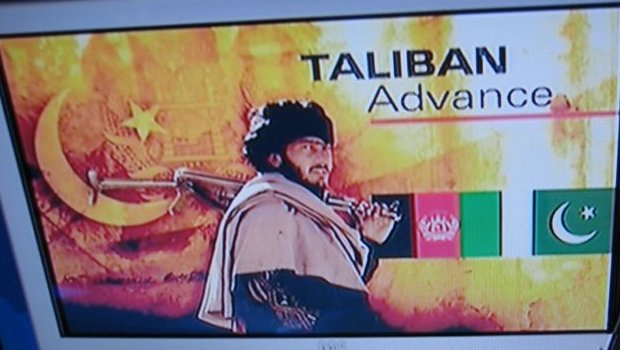

On December 28, 2014 Obama announced, “Now our combat mission to Afghanistan is ending, and the longest war in American history is coming to a responsible conclusion.” A year and a half later, on March 6, the Taliban again refused to participate in peace talks with the Afghan government saying they would not do so while foreign troops remained in the country.

Taliban leaders charged that the U.S. had increased the number of its forces in Afghanistan and was continuing to carry out bombing and night raids on residential compounds. Instead of ending the war, the Obama administration has broadened the authority of American commanders to open a new front, this time against members of the Islamic State, or ISIS, which is now active in Afghanistan as well as Iraq and Syria.

The war in Afghanistan that George W. Bush launched in 2001 to punish Al Qaeda for the 9/11 attacks, has since evolved into a hydra-headed monster that has spawned new enemies and additional reasons for continued U.S. intervention. Afghanistan’s security forces, weakened by corruption and desertions, are no match for the Taliban, ISIS, and regional tribal groups such as the Haqqani network. Lt. Gen. John W. Nicholson, Jr., the recently appointed commander in Afghanistan, confessed to the Senate Armed Services Committee in early March that the Taliban was fighting “more intensively than perhaps we had anticipated.”

To those who remembered the lessons of the Vietnam war, Nicholson’s statement came as no surprise. As the Viet Cong demonstrated, fighters defending their own territory have the advantage of powerful motivation plus a greater knowledge of the territory. Nevertheless, last month the Pentagon announced it was deploying hundreds of additional American soldiers to Helmand province, where one district after another has fallen to the Taliban.

There is, in fact, no end in sight to the U.S. presence in Afghanistan.The Afghan army remains underfed, undertrained, and under-equipped, despite years of training and billions of dollars in U.S. aid. Gen. John F. Campbell, the outgoing chief of NATO forces in Afghanistan, said as much when he told the House Armed Services Committee that “Afghanistan has not achieved an enduring level of security and stability that justified reduction in our support in 2016.”

But if 15 years of U.S. aid has not helped Afghanistan achieve security and stability, how can continuing that aid be justified?

America’s involvement in that country may in fact be the problem. Aimal Faizi, a spokesman for former President Hanid Karzai, was quoted in the New York Times on February 10 as saying: “After 15 years of a failed military operation, killings and destruction in Helmand, it is also right to worry that the local people in Helmand will no more see the Americans as a liberating force but an occupying force.” He called sending more troops to Helmand an “ill-advised” military strategy that failed to “fight the roots of terrorism.”

On the contrary, instead of effectively combating the roots of terrorism, our military strategy since 9/11 has watered and fertilized those roots. Terrorism is fueled by anger, and America’s wars in Muslim nations, and its close alliance with Israel, have provided plenty of fuel. There were 11,000 civilian casualties in in Afghanistan in 2015, but the statistics don’t “reflect the real horror of the phenomenon we are talking about,” Aimal Faizi said. The real cost “is measured in the maimed bodies of children, the communities who have to live with the loss…the parents who grieve for lost children, the children who grieve for lost parents.”

The Pentagon paid out $6,000 in compensation to each of the more than 140 families whose relatives were killed or wounded in February when American helicopters attacked two hospitals, one of them run by Doctors Without Borders in Kunduz, and the other in Wardak province funded by Sweden. A representative of Doctors Without Borders called the amount of compensation money “ridiculous.” Many of the families had lost their only breadwinner, he said.

Impossible to estimate are the long term costs to Afghan society as a whole of the influx of foreign troops and aid personnel in 2001 and after, plus the billions of dollars in funds they brought with them. According to an article in the New Yorker by Matthieu Aikins (“The Bidding War,” March 7), U.S. military operations in Afghanistan have so far cost nearly $800 billion dollars, with most of it going to private contractors, some of it going to bribes to the Taliban, and much of it funneled out of the country into bank accounts in Dubai and elsewhere. Meanwhile, poverty is endemic among the Afghan people, and more than half of Afghanistan’s children are malnourished. As Afghanistan joins the list of U.S. military ventures that failed to accomplish their purpose, more such ventures are being planned. Having successfully helped to overthrow Libyan ruler Muammar Qaddafi, the Pentagon has prepared plans to launch intensive air strikes against the ISIS forces that took advantage of the resulting chaos to move in. Fortunately, Obama has not yet decided to do so.

Considering that the next president may have to decide whether to deepen U.S. military involvement in Afghanistan and Syria or pursue more intensive peace efforts, it is all the more worrisome that these issues are so seldom mentioned in the current political campaign. Much the same was true of the Bush-Gore campaign in 2000 and as a result the nation voted into office an administration that saddled us with two unnecessary wars whose costs have yet to be estimated.