In Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict, John Judis demonstrates the power of looking back to the past to make a statement about the current political moment.

Judis is an activist journalist cum historian who writes frequently at The New Republic. Instead of moralizing about the cast of characters involved in this complicated history, as others have already done, Judis looks at the enduring themes from the “Genesis” that influence today’s Middle East.

Since the end of Ottoman rule at the conclusion of World War I, Judis details, Palestine’s fate has remained linked to Western influence. The British mandate in Palestine acted as a formal colony for London in its final imperial decades. In the mandate’s waning days, the mantle of Western leadership passed to its new leader, the United States, and its newest international institution, the United Nations. Both the United States and the UN failed to develop ideas to promote a sustainable solution to the Palestinian crisis before it broke into open warfare.

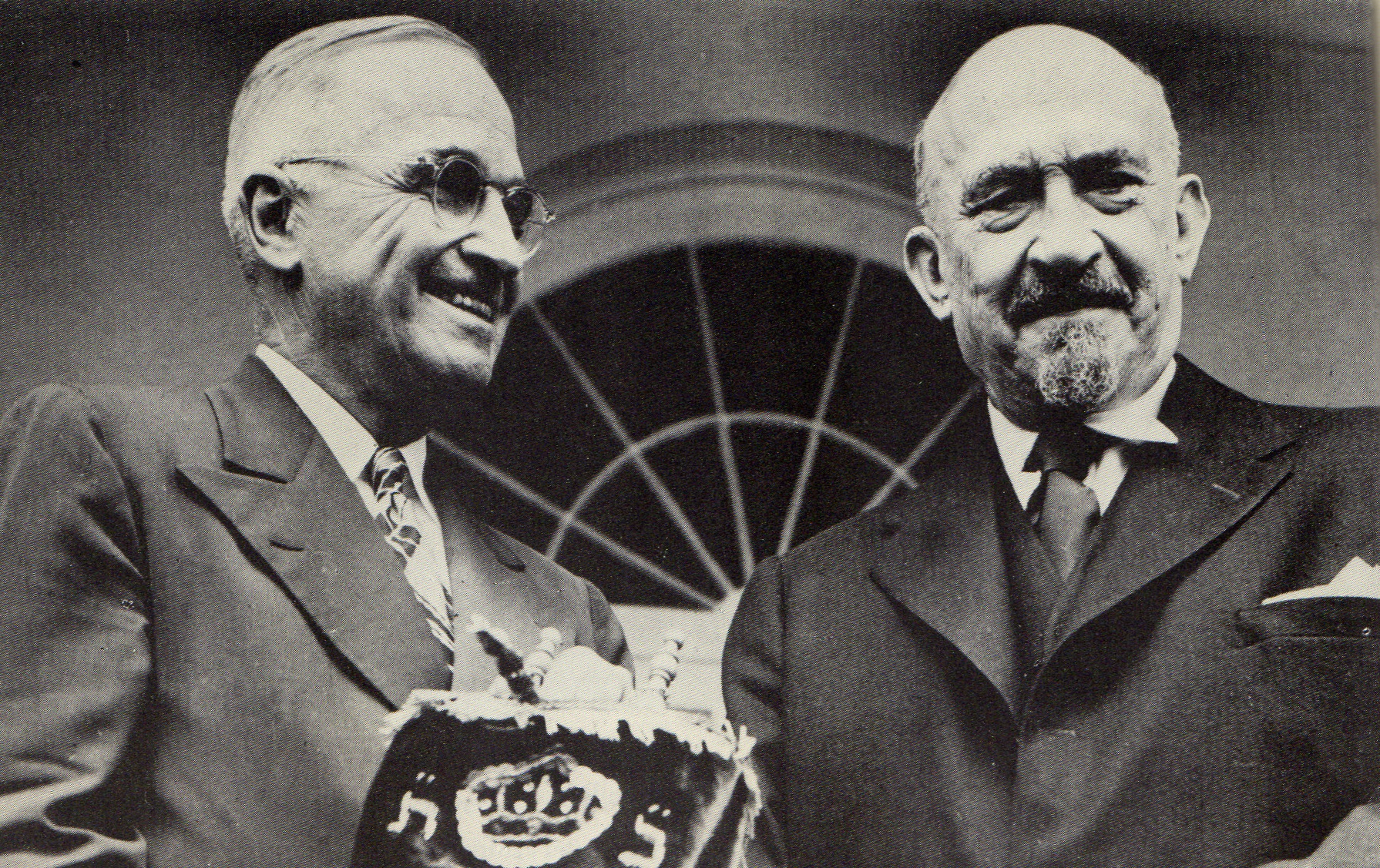

As the United States and the UN dithered, the situation on the ground evolved. The British mandate expired while President Harry Truman vacillated between the counsel of Zionist activists, political advisers, and State Department Cold Warriors over one unworkable plan after another—the critical, and sometimes exhausting, political and interpersonal dynamics that make up the lion’s share of Genesis. The Jews and Arabs of Palestine, along with the armies of Palestine’s Arab neighbors, then descended into a war that none could bring to a halt.

This story of Western ineptitude is incomplete without mentioning the second enduring theme from this period: the impact of lobbying in the West on Middle East policy. The most effective lobbyists were those who advocated for the Zionist cause, who believed, as Judis notes, that Palestine’s Jews “were still engaged in a war for survival” in a war-torn world that turned them away.

Pro-Israel activists learned to harness the power of the Jewish vote in states such as Ohio and New York to influence the actions of President Truman, who was at once a moralist and an unrivaled political animal. Transforming a Jewish community increasingly convinced of the need for a Jewish state into single-issue voters, leading American Zionists like Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver effectively pushed U.S. policy towards what they believed to be in the best interests of the Jewish people.

But each plan the Truman administration considered, as Judis acknowledges, was fatally flawed. There might have been missed opportunities to implement a workable governance structure for Palestine during British rule. But during the Truman administration, the impact of Zionist activists, both within the formal lobbying organizations and within the White House itself, often pushed President Truman to reject plans for federation and partition as unworkable.

Finally, the book makes clear that the ongoing Palestinian Arab exile and refugee crisis remain the most pressing problems. Throughout Judis’ account, ordinary Palestinians faced marginalization at nearly every turn throughout the 1948 war and beyond, turning the Palestinian Nakba into a reality. As Palestine’s Jews finally achieved their goal of creating a political home of their own, its Arabs saw their own hopes for the same dashed. For the Palestinian Arabs, the great tragedy of exile began along with the decades-long hardships of life in refugee camps. Thus began the vicious cycle of outside meddling, violence, and indifference, as well as inner political turmoil, that plague the Palestinian people to this day.

In each of these themes lie potent parallels and truths for the present. Western failures, such as the recently defeated Kerry Peace Initiative, make a greater statement about the compromised U.S. role in the region than anything else. The influence of American Jewish groups, many of which coalesce around the policies of the Israeli government, remains a strong, though neither absolute nor monolithic, force affecting U.S. congressional activity and Obama administration policy.

Though the UN and even the United States provide tangible support for the cause of Palestinian statehood, the Palestinian cause remains an aspiration. This is due in part to the enduring fact of internal political ruptures within the Palestinian camp that, despite current efforts at rapprochement, go to the religious and national core of Palestinian identity. It is also due, as Judis forcefully asserts, to the flawed U.S.-Israeli relationship that allows “Israelis to overlook what they did and are continuing to do to Palestine’s Arabs.” If peace is to come to the Middle East, surely all of these problems will need to be addressed.

But above all of this noise, the great tragedy of Palestinian exile remains unanswered. The Palestinians will be hard-pressed to accept a peace deal with Israel that does not satisfactorily remedy the plight of Palestine’s refugees. Although it’s likely not feasible for Palestinian exiles to return to communities that Israelis have lived in for generations now, it is easy to understand why this leaves so many Palestinians unsatisfied.

This nut, at the center of Genesis, is the hardest one for the Israelis and Palestinians to crack if they are to make peace. Judis writes:

[T]he main lesson of this narrative is that whatever wrongs were done to the Jews of Europe and later to those of the Arab Middle East and North Africa – and there were great wrongs inflicted – the Zionists who came to Palestine to establish a state trampled on the rights of the Arabs who already lived there. That wrong has never been adequately addressed, or redressed, and for there to be peace of any kind between the Israelis and Arabs, it must be.