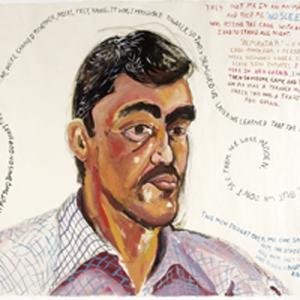

[Daniel Heyman, “They Put me in an Animal Cage,” gouache on nishinoushi paper, 2008.]

Daniel Heyman is a visual artist from Philadelphia who has been capturing the images and words of Iraqi victims of torture from U.S. facilities like Abu Ghraib. Here he talks with Foreign Policy In Focus co-director John Feffer about how he came to do this remarkable series of portraits.

John Feffer: Tell me about how you came to this project.

Daniel Heyman: I graduated from Dartmouth with a degree in visual studies. I loved Dartmouth, but it didn’t really prepare me for being an artist. I took one painting class, that was it. After I graduated I got a grant from Dartmouth to go to France. I wanted to collect memories and stories of World War II through interviews and then make paintings. I did a lot of interviews, which were really amazing, mostly from people who were children during the war and who viewed the war through a child’s eye. I spent time in a Normandy village and talked with people there about their memories of the Normandy invasion. I talked with people who helped Jews escape from northern to southern France. I talked to Jews who had been hidden as children. These were impressive and emotional interviews. But the paintings that came out of them were terrible. They were horrible. I’d never learned how to paint. Technically, I just wasn’t up to the job.

So when I was sitting through my first interviews in Amman, Jordan with former Iraqi detainees, I thought: “Ah, I’ve done this before. But now I’m up to the task of picturing them.”

This is how I got involved in with doing this work on Abu Ghraib.

I’ve done lots of different things in my art over the last 20 years. I’ve done stuff about gay and lesbian issues. I did a big painting about Nancy Kerrigan and Tonya Harding. I’ve done work on youth violence in Philadelphia. As my own visceral anger about the war built up, I didn’t really know where to put it in my artwork. I always believe that you really can’t address politics in art. Politics can be very fleeting; and art hopefully will last beyond this month or year. I also believe that you don’t choose your subject; it chooses you. So, I didn’t address the build-up to the war. But when I read the Seymour Hersh article about Abu Ghraib in The New Yorker in 2004, I boiled over. What I was doing in my studio seemed much less relevant than the fact that the United States would torture people, innocent people. I just kind of flipped.

At first I didn’t know what to do about it. Those pictures from Abu Ghraib were so awful. I started to incorporate them into my paintings at the time. These were big paintings, with lots of imagery related to lots of different things. These images from Abu Ghraib snuck in as patterns that were obvious or not obvious. The images were there, but you had to look for them. And that was what was happening in the United States, too. I thought everyone would read Hersh’s article. But not everyone did.

By the end of a year, I probably made a dozen paintings and some woodblock prints, and the potency of those images really diminished. All sorts of artists had started to use these images, and the more they were used, the more they indicated Abu Ghraib without providing any understanding of Abu Ghraib. They became a kind of code for anger about so many things to do with the war. You flash on the famous picture of the man on the box, and people become numb to that image. And you re-humiliate that man. You re-victimize that person.

Around this time I was very lucky to be introduced to Susan Burke, a lawyer in Philadelphia who was working on a case filed on behalf of the former detainees in U.S. court. She said, “Why don’t you come with us to meet some of the people you’ve been painting over the year.” The problem was that the law firm wouldn’t pay for any of my expenses. So I told her, “I don’t know if I can do it.” I’m always on the brink of financial failure. So she came over to my studio and bought a painting so that I could go on the trip with them.

In the interview process, typically, there’s the former Iraqi detainee, a translator, a lawyer running the interview, another lawyer taking notes, and me. Sometimes there’s been someone else from the arts: Kathleen Tolan, a playwright, or Jennifer Schelter, a monologist, or Nick Flynn, another writer. In the first meeting, the lawyers meet with the clients, talk to them about the case, explain what they can and can’t do for them. Then the lead lawyer says, “I’d like to introduce you to some other people who are working on your case in other ways.” And I come into the room and explain what I’m doing. I explain it’s absolutely voluntary, if any former detainee feels in any way uncomfortable, if they don’t want their image out there for any reason, they can say no. And then the lawyers explain that I spend a lot of time publicizing the case, and that they see me as integral to getting the story out in the United States. It’s happened two or three times that the former detainees say no. In one very moving interview, the person let me listen, but didn’t want to me do a portrait. In another case, a woman didn’t want any men in the interview at all. But most have no problem with it.

Afterwards, a lot of them look at the pictures and say, “I don’t look like that old” or “My nose is not really that way.” It’s just like what everyone says about their portraits.

John Feffer: Can you tell me about your decision to use images and text together? Were you consciously connecting to a particular artistic tradition?

Daniel Heyman: I definitely did not think of connecting to any artistic tradition. Up to that point, I might have put some words into my prints — “Betty in her house in Truro” underneath a print, for instance — that was the extent to which words made it into my work. I never really liked words and pictures. I thought that paintings should speak a language as rich as literature. But I’m not so sure any more.

When I went to the first interview in Amman, I started to do a man’s portrait on a copper plate with a stylus. I was listening to what he was saying, but I had no notion that I would put his words into the print. Half an hour into the interview, it overwhelmed me. What he was saying was so much more valuable than a picture of him. As interesting as it might be to work on his eyebrows a little more, it had greater meaning to put down his words. Coming to the United States just with a portrait and having to explain the story was not going to do it. If I was going to be responsible to these people at all, in terms of the gift they were giving me, I had to get their words into their artwork.

John Feffer: The words often follow a certain design in the prints. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

Daniel Heyman: I’m always interested in the surface of the work. That’s where the artist makes decisions to engage the viewer long enough for them to get the meaning of the work. You work a design to keep the engagement of the viewer.

I’ve now heard 35 interviews. I’ve heard many times about people arrested in the middle of the night, so the shock has worn off a bit. But listening to someone telling me these things, the room still fills up with a very personal thread of words. The words become a physical thing and weigh people in the room down. So, I wanted the words to feel like an imprisonment, like a cage surrounding a person. At other times I wanted the words to feel like a stream pouring out of a person.

In one of the prints at the American University exhibition, it’s hard to read the text. That’s because it’s written backward. You see, in order for the words to be read forwards, I have to write them backwards. I was listening to a man describing a terrible moment of torture. He had his foot broken. He was forced to stand on a concrete cube and an American came and broke his foot. He told a series of horrifying things. And I was so upset by what I heard that I forgot to write the words down backwards. So, you see, sometimes the form of the words is dictated by what happens in the interview. Overall, I want the viewer to feel as though they’re in the interview.

John Feffer: Fernando Botero has received a lot of coverage for his paintings of Abu Ghraib. What do you think about those paintings?

Daniel Heyman: I saw his pictures when they first came out — in Rome in June 2005. I’d been working on my first Abu Ghraib stuff for a year. Then I saw the pictures by Botero, who had been working on them for a year. They are very powerful pictures, no doubt about it.

After that first year, around the time I saw the Botero paintings, I was thinking: I can’t do pictures like this any more. They continue to deny the individuality and the full life stories of the former detainees. After I saw the Botero paintings, I met the people in the paintings, for instance someone whose testimony seems like he might be the man on the leash. I sat in the room with him for many hours while he talked about his ordeal. And there was a man we call Haj Ali, who was tortured at one point by being made to stand on a box, hooded, with electrical wires attached to his hands, and told that he would be electrocuted if he fell of the box. The torture sounds like the infamous picture of the man on the box that we see everywhere. I listened to men who were strung up on prison bars with women’s underwear on their heads, others who were raped with broomsticks. And I find the paintings of them by Botero — the way they were pictured by the people who tortured them — to be disturbing. These paintings make a strong political point, but they don’t go any further. They make a generalized point about human suffering, but they don’t say anything particular about the individuals who suffered. That’s not to say that they aren’t beautiful or moving. And they certainly bring more attention to this issue than my pictures have.

Botero is a famous artist who certainly didn’t have to spend a year of studio time doing this kind of work. Richard Serra also did a print. I don’t know why other artists haven’t. This war is very difficult for artists. There’s very little information, very few opportunities to go to Iraq to see first hand what is going on. As visual artists, we need to see things, and we don’t have that opportunity. It’s hard to get upset about things on paper, things that have already been digested. For Botero to have brought world attention to these issues through his work is a very strong statement.

On the other hand, I’m really upset about Errol Morris’ film Standard Operating Procedure. They could have met any of the Iraqis they wanted to, and they simply made a film that repeated the soldiers’ story. Errol Morris has made great films. Susan Burke told him that they could get him access to the detainees. For Morris not to look at the Iraqi point of view, and to make a film about how difficult it was to be an unprepared U.S. soldier in Iraq seems to have missed an opportunity to tell a much more important story.

It was not responsible for the film to repeat the nickname that Lynndie England gave to the man she dragged around on a leash. We might not know his real name, but it certainly was not “Gus.” England says he was a disruptive prisoner. Based on testimony I have heard from many tortured Iraqis, that picture must have been taken during some pretty horrific torture. If Morris was going to show England’s point of view, at least he could have said, “Okay, and now here’s is the testimony of an Iraqi whose story is very different, very real, and very painful.”

John Feffer: What have been the reactions to your work?

Daniel Heyman: I’ve been much pushier about getting this work out to the public because the work contains issues that are bigger than my clever visual puns or my personal career. Three of the people in my pictures were killed back in Iraq, their own voices now silenced. So I feel responsible to those who have trusted me with their stories to try hard to get those stories heard in the United States.

I had an exhibition of many of these prints at The Print Center in Philadelphia, with the framed prints hung around the walls of the gallery. On the floor of the gallery, I stenciled the text from an interview with a woman detainee. This detainee was one of the few who did not allow me to listen to her interview. She had been raped at Abu Ghraib and it had been very humiliating, and she did not want a man to listen to her recounting the torture. Several months after the interview with her lawyers, after she returned to Iraq (the interview had taken place in Jordan), she was kidnapped, raped, mutilated, and murdered. I wanted to do something to memorialize this woman who had suffered so much, and asked for the family’s permission to create a memorial using the text of interviews. They said yes. I stenciled the words onto the floor of the exhibition in the shape of a Muslim prayer rug. In order for visitors to see the exhibited prints, therefore, you had to walk over her testimony.

One night I gave a public talk in this exhibition. The following day I received an anonymous reaction by email. The email said it was very powerful work. Then the writer pointed out that in Muslim culture, you have to take off your shoes before going into a mosque. Then the writer said, “How do you know these Muslims are telling the truth anyway?” It got really nasty by the end of email, but there was no name attached to the email. I replied by saying, “Look, I talk to anyone about anything. But you have to tell me who you are.” Turns out it the email was written by one of the American soldiers found guilty for her role in the Abu Ghraib torture case.

People tend to be very stunned when I give this talk. Last spring I gave a talk to a class at the Barnes Foundation outside of Philadelphia and afterwards there was a sense of disbelief among some of the students. “Are you sure that this really happened?” they asked. But this has been all over the newspapers. What did they think those articles were about?