This article was originally published by The Nation on Oct. 22.

The Nobel Peace Prize committee can, when it gets it right, present to the world unlikely heroes who can inspire us to rethink what it means to “wage peace.”

This year, the committee got it right by honoring not only Malala Yousafzai, whose first name alone elicits widespread recognition, but also Kailash Satyarthi, a little-known hero with a big story. We have both been privileged to work with Kailash over decades of involvement in two groups, which he helped to shape, that are at the forefront of the fight against child labor: GoodWeave (formerly RugMark) and the International Labor Rights Forum.

The Nobel committee got it right in part because its members embraced the wisdom of the adage that “you can’t have peace without justice.” And they were clever in drawing attention to the conflicts between Pakistan and India by honoring a person from each of these countries, one female and one male, one younger and one older, one Muslim and one Hindu.

Malala’s story is well-known, Kailash’s far less so. What can he teach us about peace and justice? Well, quite a bit.

Early on, Kailash built organizations that freed children from lives of grueling “bonded” slave labor, some of them as young as 4, shackled to carpet looms in horrific conditions. If the children tried to escape, Kailash explained, “they were hanged upside down on trees and beaten with stones. Their legs were broken so they couldn’t run away again.”

Among the many aspects of Kailash’s work missed by most journalists is just how dangerous being a “liberator” is. Few parts of his body have been spared broken bones, and he has been in numerous situations where he could have been killed. He and his family and colleagues have been jailed, and at least two of his co-workers have been murdered.

Kailash began this work in his native India with the Bachpan Bachao Andolan, which he founded in 1980. He also helped found the South Asian Coalition on Child Servitude, which links his group to similar ones in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and elsewhere.

Hence, one of the first things we learn from Kailash is that it is a dastardly myth that only richer people in richer countries care about ending child labor. Indeed, it was Kailash and his co-workers who took the lead in acting to end the dreadful plight of these children. His simplest goal was to ensure that every child has a childhood.

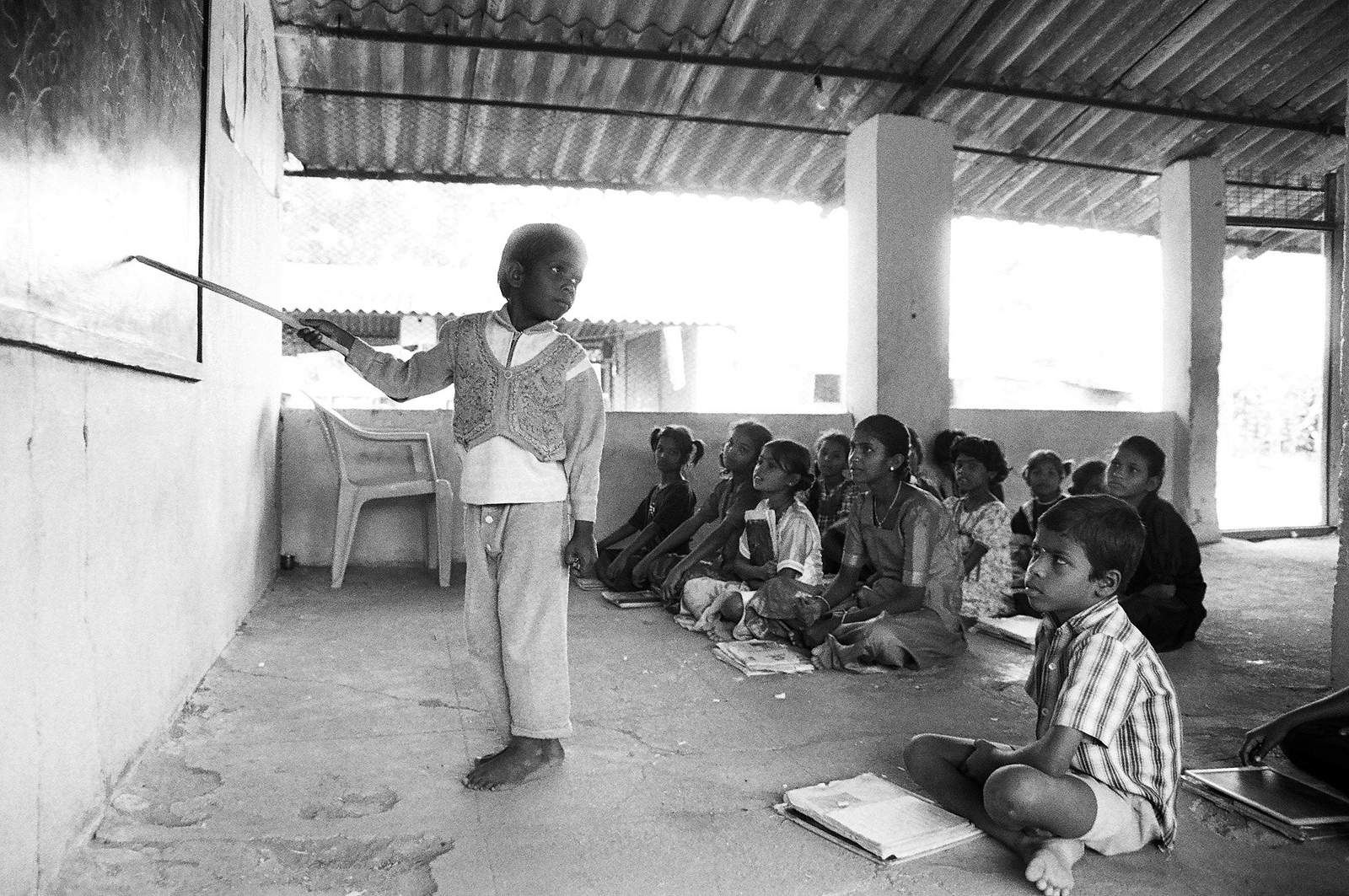

Kailash quickly grew to understand that the struggle was about much more than freeing children, and he pulled the global anti-child labor movement in this direction. These children also needed—and wanted—education.

Pushing even deeper to name the roots of the problem, Kailash found himself facing India’s brutal caste system. He recounts asking a cobbler why his son was not in school. The response: “We are born to work.” Kailash refused to accept that. As he and his colleagues stress, contrary to widely held beliefs, child labor does not solve poverty. Indeed, he pointed out that “child labor perpetuates poverty” by perpetuating the inequities that lead to child labor in the first place.

Kailash has also consistently named the global power dynamic that exploits children, starting with corporations. “The corporations are the most responsible…. Children…cannot form their unions, they cannot go to the court of law…. The corporate sector must be honest in admitting the very fact that large numbers of children are enslaved, sold and bought like animals, and working in their supply chains,” Kailash stressed last year on the World Day Against Child Labor.

Part of Kailash’s genius has been guiding people in both the global South and North into new ways of acting. He was instrumental in creating GoodWeave, with its certification system for carpets made without using child labor. He certainly is not naïve enough to think consumers are the full answer to the ills caused by powerful global corporations or the divisions among economic classes, but he is wise enough to recognize that you can’t have a solution without consumers.

Thanks to GoodWeave, anyone who wants a hand-loomed carpet now has a choice. Based in key producer countries (India, Nepal, and Afghanistan) and consumer countries (the United States, Germany, and Britain), GoodWeave created a system of monitoring and enforcing the certification of carpets that gives an incentive to companies to end child labor, to employ adults in dignified skilled work, and to court consumers who want to buy carpets that aren’t made with child labor. Millions of carpets labeled free of child labor have been sold in Europe and the United States, and the proceeds have helped educate and rehabilitate countless children in India and other countries.

Kailash expanded our creativity as actors in history in another way. The two of us remember his excitement and audacity in the mid-1990s in dreaming up the Global March Against Child Labor, with labor rights visionaries like Pharis Harvey, then director of the International Labor Rights Forum and Kailash’s longtime co-dreamer. Under Kailash’s leadership, hundreds of thousands of children and their advocates in dozens of countries marched to tell the story of de facto child slavery and to demand a stronger global convention banning child labor. We remember vividly the end of the U.S. leg of the march in 1998. Senator Tom Harkin embraced the weary marchers, Kailash among them, on the National Mall in Washington in front of the Capitol, before the march’s final stage in Geneva at the International Labor Organization. Because of the publicity generated by the march and the clarity of Kailash and his colleagues, the ILO convention on the worst forms of child labor was ratified quickly by more than 150 countries.

Bravo, Nobel committee. Bravo, Kailash.