Robert Burns of the Associated Press has been the lead dog on stories about “rot” in the U.S. nuclear force. Earlier in the year, he reported that the 91st Missile Wing at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota “earned the equivalent of a ‘D’ grade when tested on their mastery of [nuclear missile] launch operations using a simulator.” Subsequently, 17 officers and a commander were removed from duty.

By way of back story, Burns writes:

The trouble at Minot was the latest in a longer series of setbacks for the Air Force’s nuclear mission [which included] the inadvertent transport of six nuclear-tipped missiles on a B-52 bomber … from Minot to Barksdale Air Force Base, La.

In August of this year a unit at Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana, home of one of the two other nuclear missile wings, failed a safety and security inspection. Then, Burns reported on November 20, “Key members of the Air Force’s nuclear missile force are feeling ‘burnout’ from what they see as exhausting, unrewarding and stressful work, according to an unpublished study” by the RAND Corp. that the Air Force commissioned.

The finding … adds to indications that trouble inside the nuclear missile force runs deeper and wider than officials have acknowledged. [It] also cites heightened levels of misconduct like spousal abuse and says court-martial rates in the nuclear missile force in 2011 and 2012 were more than twice as high as in the overall Air Force.

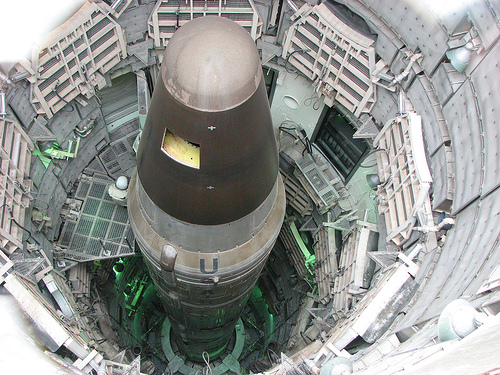

Of course, writes Burns, “This has always been considered hard duty, in part due to the enormous responsibility of safely operating nuclear missiles,” especially during the Cold War. But, as tensions between the United States and Russia have ratcheted down (to some degree, anyway), “the nuclear threat is no longer prominent among America’s security challenges.” In fact, the “arsenal has shrunk ― in size and stature.” As a result: “The Air Force struggles to demonstrate the relevance of its aging ICBMs in a world worried more about terrorism and cyberwar and accustomed to 21st century weapons such as drones.” Burns quotes a missileer (as they’re called), who recently completed a tour of duty.

“We all acknowledge their importance, but at the same time we really don’t think the mission is that critical,” … adding that his peers see the threat of full-scale nuclear war as “simply nonexistent.” So “we practice for all-out nuclear war, but we know that isn’t going to happen.”

Another said:

“We don’t care if things go properly. We just don’t want to get in trouble.”

A disarmament advocate such as myself can’t help but speculate that the futility they’re experiencing begets the kind of carelessness that can lead to an accidental launch. Also, I may be giving them too much credit, but I wonder if today’s missileers, raised in a culture that’s become as much anti-nuclear as it is pro-, are susceptible to bouts of conscience about the devastating impact of a launch that they might still yet be called upon to carry out. Most likely, though, as the RAND report sums up, it’s just “a toxic mix of frustration and aggravation, heightened by a sense of being unappreciated, overworked, micromanaged and at constant risk of failure.”

In other words, the most frequent causes of workplace accidents. Recently I quoted Martin Hellman in a post commenting on a speech before STRATCOM made by Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel, in which he said: “Perfection must be the standard for our nuclear forces.”

Unfortunately, saying that perfection is required, does not mean perfection is achieved. After all, “to err is human.” So why are we relying on nuclear deterrence when just one mistake could destroy our homeland, and us along with it?

It also needs to be borne in mind that carelessness is only one of the problems posed by disgruntled employees. They’re also capable of ― however unlikely in a field as locked down by security as nuclear weapons ― theft, unauthorized distribution of files, and, of course, sabotage.

We worry about who’s in control of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons. We need to take a look in the mirror.