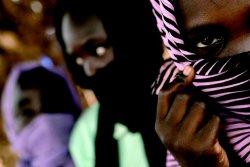

Sudanese girls seen in Darfur, Sudan, June 25, 2005. The 12-year-old girl wearing the striped scarf, front, reported how she was separated from her two friends, and raped by soldiers from the Sudanese government. Photo by R. Haviv

Brilliant colors are not often associated with tragedy. Tombstones are appropriately gray, and scary stories always begin on dark, dreary nights. Bright colors are usually reserved for children’s birthday cakes or the sky at sunset. Given these natural associations, color has an impressive ability to surprise. Imagine a group of African women clothed in deep reds, fiery oranges, and emerald greens. Set against a pale blue sky, the descending sun casts shadows that heighten the luminosity of their garments. The darkness of their skin and the drab brown of the firewood in their hands further accentuate the colors.

In a perfect world – indeed, even in a moderately just world – such an image would be found only in a guide book, or perhaps alongside an encyclopedia entry. But this photograph appears in Lane Montgomery’s Never Again, Again, Again and its subject matter is as grim as it gets: genocide. The women are from Darfur. They are gathering firewood, which is typically a man’s job. However, since roving militias only rape women who stray from their villages – the men are always murdered – the task has fallen on females, who might at least survive attack.

In other photos in Montgomery’s new book, women flee from rape and abuse, men flee from torture and murder. At the same time, we see the Technicolor radiance of Darfur’s indigenous population as well as the multifaceted beauty of African landscapes. In another photograph from the collection, a pile of light brown donkeys, who died from exhaustion while refugees fled from Darfur to Chad, is set ablaze, giving us searing oranges and ashen blacks, set against the soft sand of an African desert. One can only wonder what happened to the people.

Photographs such as these upset our entire notion of genocide, for they make widespread death and systematic murder look alive. This ability of pictures to capture our attention is partly due to the inability of language to grapple with a reality as stark as genocide. Few of us ever see it with our own eyes. And no matter how many times we say “genocide” or ponder its meaning in the abstract, no word can adequately convey the intentional extermination of hundreds of thousands of human beings. Full-color photos are particularly distressing. They imply that genocide is not a thing of the far-off past, but something going on today. Our standard black-and-white images, which come from textbooks or films like Night and Fog and Schindler’s List, seem to consign genocide to an unfortunate time gone by. Alas, genocide is still very much with us.

Never Again?

From the brutal campaigns of Genghis Khan to the terrible crimes of the Spanish Inquisition, men have committed acts of unspeakable barbarism against one another. While this is a phenomenon reaching back across millennia, the 20th century marked a revolution in man’s inhumanity to man. The combination of ethnic nationalism, fanatical ideology, and new technology produced slaughters of hitherto unseen efficiency and unimaginable wickedness. In less than 100 years, Stalin’s gulags and Hitler’s Holocaust, among other grotesqueries, led to the deaths of more than 50 million human beings. By 1948 the massacres had grown so staggering that the international community created a whole new crime to describe it: genocide. After the Nazi extermination of European Jewry, the victorious Allies swore they would never allow such carnage to happen again.

But carnage did happen again – and again and again and again – in the killing fields of Pol Pot, in Rwanda, in Bosnia. Indeed, genocide became one of the 20th century’s grisliest themes. Lane Montgomery’s Never Again, Again, Again captures in a single volume of photographs and historical commentary all the abject viciousness of last century’s systematic campaigns of murder.

In Rwanda, a photograph taken inside the technical college school in Murambi shows the machete-scarred remains of slaughtered men, women, and children. Over a period of four days 40,000 people were hacked to pieces on these premises. Laid out on tables and sprinkled with lime, the corpses have turned alabaster white. Another photo captures the legacy of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. A young boy stands against a pillar on a wooden deck. In the background are green trees, white flowers, and a colorfully decorated temple. But in the foreground of the picture is an iron cage filled with bones: skulls, spines, legs, hips, and arms. The boy’s impassive face suggests that there is nothing abnormal about the skeletal remains of massacred innocents. With images such as these, Montgomery’s photographic essay demonstrates that methodical murder is no anomaly. It is a recurrent event that some commit and others allow, time and time again.

“Genocide takes a group, not just you and me killing somebody,” Montgomery told me during an interview. From the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide in the late 1940s to the “Save Darfur” banners of today, well-meaning men and women have frequently proclaimed their willingness to stand against genocide, only to see it occur yet again. Her book is a reminder that words are not enough and that timid bystanders – you and me – are every bit as essential to genocide as executioners and victims. “You can’t let something go on so long…you really have to do something about it or accept the fact that you’re not going to do anything about it.” Never Again, Again, Again is thus a call to conscience that leaves the reader determined to act and give meaning to the oft-repeated slogan, “never again.”

Darfur/Darfur

Montgomery is not alone in bringing genocide into consciences around the world. Leslie Thomas is the creator and director of Darfur/Darfur, a traveling multimedia exhibit whose goal is to raise awareness of the genocide in Sudan and advocate for peace. From a chance encounter of her own, Thomas went from knowing little about Darfur to traveling the world on behalf of its victims. “Sometimes it’s the visual that overcomes the intellectual hesitation to get involved,” she writes in an email. While surfing the Internet during a late-night feeding of her infant son in March 2006, Thomas came across a photograph of a young Sudanese girl with a bullet hole in her back. She spent hours crying, thinking of her own young child. The next day she began cold-calling prominent photojournalists and Darfur/Darfur was born.

The power of Darfur/Darfur lies in the size and beauty of its images, which are beamed onto walls or large screens in public places, visible to any passersby. The sheer magnitude and inescapability of the exhibit drive home the enormity of what’s taking place in Darfur. Working with local curators and nongovernmental organizations, each city Darfur/Darfur plays in makes for a slightly different show. Yet, according to Thomas, the response is always similar: “a core sense of frustration, anger, and a desire for action – all of which I think is appropriate.” Audiences from a dozen cities throughout the United States have already experienced Darfur/Darfur since it began to tour America in 2006. Thomas has also taken her show abroad to Canada, South Africa, Germany, France, Turkey, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, Portugal, Croatia, Slovenia, and Senegal. More exhibits are currently in the works, and the next scheduled stop for the tour is Valencia, Spain in June 2008.

For those who have not had the opportunity to see a showing of Darfur/Darfur, the website provides a slide show of some of the exhibit’s photographs. Several of them are taken in or near small villages, which builds up to one of the final pictures of the slide show: an aerial shot of a burning house in a small village. The image is disturbing on a number of levels. First, it’s impossible to know whether the house has been set on fire or bombed from above. We’re also not told the fate of the rest of the village. Do the flames remain confined to one single house, or do all the houses – with their thatch roofs, makeshift fences and tiny trees – succumb to the fire? Where are the people? Have they fled, or are they burning as well?

The photographs leave open-ended whether Darfur has any would-be rescuers. We see soldiers in a truck bearing rifles and others near a village bearing a machine gun, but we don’t know who they are or whether they’ve come to kill or to heal. A less ambiguous photograph depicts a boy standing in a field of sand and black rock. A single scrawny tree adorns the foreground. In the distance lie a bluff and a ridge of small trees. Sand is spinning and the boy’s garments are blowing, but not due to any natural causes. Instead, the swirling winds are whipped up by a white UN helicopter, which is flying away to an unknown destination. Although it may very well be going to contribute to good work elsewhere in Sudan, the helicopter nonetheless seems to be leaving the boy, and all of Darfur, to their fate, whatever that might be.

Genocide Today

Thanks to the artistic efforts of activists such as Thomas and Montgomery, Darfur is now recognized as a genocide by millions of people who most likely had never heard of it two years ago. Religious organizations, human rights groups, and concerned citizens have mounted public campaigns, bolstering public knowledge and leading to political action in the form of divestment legislation and the deployment of peacekeepers in the Sudan. President George W. Bush, who is hardly a darling to human rights activists, has rightly and consistently referred to Darfur as an instance of “genocide.” According to one poll, nearly 65% of Americans are willing to send troops into Sudan to stop the killing in Darfur.

Yet when I asked Montgomery whether such developments constituted progress in the international community’s commitment to prevent and arrest genocide, she responded with a slightly despondent “I don’t know.” As our conversation went on, the outlook became more sanguine. “I’m sure we’ve made some [progress], but it’s not enough to stop the genocide.” This points to a reality every bit as disconcerting as the association of lively colors with unbridled death. The situation in Darfur proves that the international community is still perfectly capable of allowing a genocide to take place without putting up a serious fight.

This is not to underestimate the difficulties of effective action. When prevention fails, the first obstacle to intervening to stop a genocide is the issue of sovereignty. Modern conceptions of state sovereignty, according to which countries can do as they wish within their own borders, has been the backbone of international law since the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. Outbreaks of genocide have led the international community to rethink this principle. As Kofi Annan put it 2000, “If humanitarian intervention is indeed an unacceptable assault on sovereignty, how should we respond to a Rwanda, to a Srebrenica, to gross and systematic violations of human rights?”

The answer to this question, now ratified in a Security Council resolution, is the Responsibility to Protect (R2P). Countries, well-intentioned or otherwise, do not have a “right to intervene” when mass murder breaks out elsewhere. Rather, the international community has a responsibility to protect those people whose countries will not or cannot uphold their basic human rights. In his final speech as UN secretary general in 2006, Annan summed up R2P by stating that “respect for national sovereignty can no longer be used as a shield by governments intent on massacring their own people, or as an excuse for the rest of us to do nothing when such heinous crimes are committed.”

Even with R2P in place, countries are hesitant to violate the traditional understanding of sovereignty. Others insist that intervention on the basis of human rights is a smokescreen for Western neo-imperialism. Practical problems abound as well. Who is the international community to which the Responsibility to Protect refers: the UN, NATO, coalitions of the willing? There is simply no universally accepted definition of who constitutes this “international community.” Intervening to stop a genocide also demands military action, can be extremely costly, and could provoke unintended consequences. These, and a host of other issues, make it difficult to take action against genocide once it breaks out.

Such obstacles are real and must be taken seriously. Although the immorality of genocide is abundantly clear, it is an enormously complex issue that doesn’t fall into easy black-and-white solutions. With photographs as colorful as genocide is complicated, Darfur/Darfur and Never Again, Again, Again reflect this reality and reinforce the challenges of responding to genocide, while encouraging us to do more to meet those challenges as they arise.