A common flaw in U.S. foreign policy is the politicization of foreign assistance. Whether Republican or Democratic, U.S. administrations allow narrowly defined “national interests” – instead of needs, priorities, and realities in a given country – to dictate foreign assistance. As a result, foreign aid often backfires, undermining long-term U.S. interests and fueling instability, conflict, and violations of core human rights standards. Nowhere is this truer than in Central Africa’s Great Lakes Region. Today, President George W. Bush supports corrupt, illegitimate regimes that will either cooperate in the Global War on Terror, provide U.S. companies access to vital natural resources, or both. If history is any indication, this infusion of wealth and military training is likely to be disastrous for the people of Africa.

A common flaw in U.S. foreign policy is the politicization of foreign assistance. Whether Republican or Democratic, U.S. administrations allow narrowly defined “national interests” – instead of needs, priorities, and realities in a given country – to dictate foreign assistance. As a result, foreign aid often backfires, undermining long-term U.S. interests and fueling instability, conflict, and violations of core human rights standards. Nowhere is this truer than in Central Africa’s Great Lakes Region. Today, President George W. Bush supports corrupt, illegitimate regimes that will either cooperate in the Global War on Terror, provide U.S. companies access to vital natural resources, or both. If history is any indication, this infusion of wealth and military training is likely to be disastrous for the people of Africa.

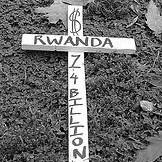

Rwanda is an excellent case in point. While many link Rwanda with internal issues of genocide, a similar atrocity is underway with the current regime of Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame. As Kagame hosts President Bush this week, Rwanda continues incursions across the border into the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with support from the U.S. government. Will the leader of the most powerful country in the world have the courage to discuss Rwanda’s negative role in peace and economic development in the DRC? Will Bush castigate Kagame for not providing the political space for Hutus to return to Rwanda? This is not likely because of the strategic value of coltan, a metallic ore extracted from Central Africa, without which cell phones, computers, and other technologies cannot be made.

From 1996-2003, the Congolese people suffered a great deal from two wars that pitted Rwanda and its allies against the DRC. A recent report from the International Rescue Committee estimates that 5.5 million Congolese have died as a result of this conflict. According to Inter Press Service journalist Tito Dragon, “to control coltan mines that was the principal, if not the only, motivation behind the U.S.-backed 1998 occupation of part of DRC territory by Rwanda and Uganda.” In fact, in 2004, after a three-year investigation, a UN Panel of Experts implicated three major U.S. companies (Cabot Corporation, Eagle Wings Resources International, and OM Group) for fueling war in DRC by collaborating with rebel groups trafficking coltan. In spite of major human rights violations, Bush administration assistance to Rwanda continues today largely due to Kagame’s willingness to be engaged in the so called War on Terror.

Although Kagame publicly denies any direct involvement, Rwandans acknowledge that their president funds renegade General Laurent Nkunda’s militia in the DRC – a militia whose primary purpose appears to be to keep Hutu rebels away from the Rwandan border. UN peacekeepers accuse Nkunda’s Tutsi faction of some of the worst human rights abuses of any rebel group currently operating in the eastern region.

Bush knows that Rwanda’s involvement in the armed conflict in the DRC delays peace in eastern Congo, but he continues to authorize military aid to Rwanda. In 2007, the United States armed and trained Rwandan soldiers with $7.2 million from the U.S. defense program Africa Contingent Operations Training Assistance (ACOTA) and $260,000 from the International Military and Education (IMET) program. At the same time, the United States is involved in facilitating peace talks between Rwanda and the DRC and the various rebel groups operating in eastern Congo. Not only does arming Rwanda contradict the peace process, but it also delays the recovery of Rwanda from its 1994 genocide.

During the Cold War, the United States provided military aid to African countries to counter communism. Many of those countries – Somalia, Sudan, and the DRC – have now become hotspots of violence and economic chaos. It is no surprise that lending arms and financial support to corrupt dictators and human rights abusers contributes to destabilization, but still the U.S. government has yet to learn its lesson. Today, the rationale for providing military aid to countries like Rwanda is to counter terrorism; the methods and outcomes will likely be the same as they were in the Cold War era.

The Department of Defense argues that training and equipping African military forces will bring greater stability and legitimacy to African governments. This argument for professionalizing militaries was also made during the Cold War to support a policy that ultimately failed. Yet the same justification is being used to mask U.S. corporate interests in Africa’s vast resources.

President Bush has the opportunity to encourage African governments to engage peacefully and democratically with their people and their neighbors. This can only be done if African nations see the administration’s actions as legitimate. Most countries have vehemently rejected the creation and implementation of a new U.S. military command for Africa (AFRICOM) and expanding the U.S. military footprint in Africa. Shifting U.S. policy away from defense toward human security, development, and diplomacy is the best path to long-term peace in the Great Lakes region and throughout Africa.