The United States nuclear missile force has been beset by a series of issues that Robert Burns of the Associated Press, who has been the lead dog on this ongoing story, describes as the “deliberate violations of safety rules, failures of inspections,” and “breakdowns in training.” The latest, as you may have heard, is cheating by the “missileers” on proficiency exams. There’s been much handwringing on the part of the command, including Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel, who wondered aloud: “Do they get bored?” he asked. No doubt; also, as Burns explains:

Nuclear missile duty has lost its luster in an era dominated by other security threats. It’s rarely the career path of first choice for young officers.

They can see the writing on the wall. Nuclear weapons may be a century away from being abolished. But in this year’s Omnibus Spending Bill, six percent of funding was cut from what the National Nuclear Security Administration asked for warhead research, development, production, and related activities.

Meanwhile, recently appointed Secretary of the Air Force Deborah Lee James, reports Brian Everstine at the Air Force Times, says she is “going to get to the bottom of this.” She goes Hagel’s concern one step better and trots out her empathy:

“The need for perfection has created way too much stress and way too much fear.”

Of course, neither is Secretary James averse to taking the approach of executives everywhere and pointing fingers, labeling the incident as “a failure of the integrity on the part of certain airmen.” “In short,” Everstine quotes James, “we need to work to make this career field, in fact and in perception, something that young airmen want to do.” Apparently towards that end, she “outlined several issues that she has taken away from her visits to the bases and from talking to airmen.” To this author her talking points provide inviting targets.

■ The Air Force doesn’t incentivize good work by airmen, but instead has created a culture that places an emphasis on perfection and punishing anything less.

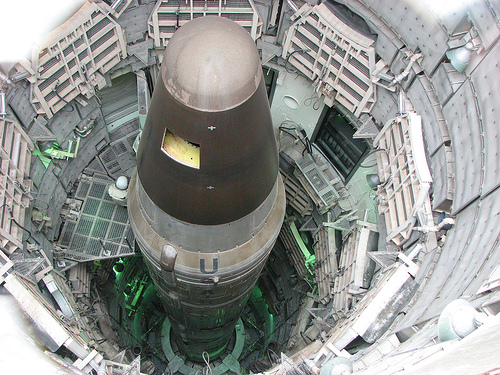

Then a missileer will be forgiven if he or she launches a nuclear strike by mistake? In fact, a key drawback of relying on nuclear weapons as the cornerstone of your national-security policy is that a mistake ― one deviation from perfection, if you will ― can result in a nuclear war. Especially with many of them programmed to launch on alert (or on a signal that nukes have been launched against the United States, enabling us to launch ours before they’re taken out).

■ Micromanagement needs to be replaced by a culture of empowerment.

As in: missileers should feel free to exercise their judgment when to launch? (Sorry, couldn’t resist.)

■ The missile forces need better funding. The airmen are told their mission is important, she said, but the service doesn’t follow through with enough funding. Among areas that could be addressed by better funding are pay, for officers and enlisted, and military construction to address quality-of-life problems.

XBox Ones for all! Actually, more funding for nuclear weapons (God forbid) would probably go further towards improving missileers’ morale than a boost in pay.

■ Problems exist with commissioning and training missile officers at Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif. The service will review if the officers are getting the right leadership training and making sure they have proper career path opportunities.

In other words, an escape route.

What’s seldom acknowledged is that, with the passage of time, the odds of a nuclear accident occurring are increasingly against us. Trying to manage nuclear weapons is like trying to hold a tiger by the tail. In fact, the phrase itself ― nuclear management ― is an oxymoron.