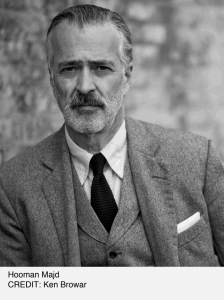

Few, if any, working journalists today have the access and insights to Iranian politics and society that Hooman Majd has. Born in Iran but raised abroad as his father—a diplomat during the Shah’s reign—took him to Africa, India, the United Kingdom, and the United States, Majd, 56, has established himself as a respected observer of the Islamic Republic. He balks at being identified as an “Iran expert” though, pointing out that many so-called experts (he includes himself), have been wrong about Iran in the past.

Formerly an executive at Island Records, Majd started writing about his homeland after 2003 when, under President Mohammad Khatami (related to Majd by marriage), it became easier for dual-national Iranians to travel back to Iran.

Since 2008, Majd has written three books on Iran: The Ayatollah Begs to Differ, a study of the paradoxes of modern Iran; The Ayatollahs’ Democracy, a multi-layered examination of Iranian domestic and foreign politics; and Majd’s most personal book, The Ministry of Guidance Invites You to Not Stay: An American Family In Iran (published by Doubleday, November 2013).

Despite his liberal, secular tone and ironic, sometimes irreverent commentary, Majd has been accused of being a mouthpiece for the Islamic Republic (Fox News recently labeled him a “Pro-Iranian Regime journalist”). At the same time, he is closely scrutinized by the Iranian government and has been warned not to get too cozy with “the Americans” (Majd himself is an American and proud New Yorker).

I spoke with Majd this October about life in Iran under sanctions, Iran’s new president, and the possibility of a new relationship between Washington and Tehran.

Hooman Majd

Jon Letman: You’ve said that Iranians are directly affected by foreign policy in ways that Americans are not. The sanctions are an obvious example. What did you experience living in Iran?

Hooman Majd: Under this sanctions regime the currency has dropped in value; everything has become much more expensive. And because salaries don’t go up according to inflation, everyone is squeezed. It affects people on a daily basis—the price of bread, the price of wheat, the price of grain, everything goes up even if it’s domestically sourced.

I had a friend who had cancer. There was no more cancer medicine available. And even if you could find it, it had gotten too expensive because it was all black market stuff.

The really harsh, most draconian sanctions on Iran happened after we left.

Jon Letman: Now there’s a debate whether to loosen sanctions or keep on the heat and “double down.”

Hooman Majd: I think it is wrong-headed to think that “doubling down” will change any minds in Iran. Iranians have lived through some pretty tough times already—especially the Iran-Iraq war, when there were actual Scud missiles falling on Tehran and the whole economy was in tatters because of the war.

Nationalism will, at the end of the day, trump even bad foreign policy decisions on the Iranians’ part. They will survive. I don’t think that Iran is willing to become another client state of the United States, or just roll over and just say we give in because you’ve really screwed us to the point where we can’t live anymore.

If America thinks that the weaker Iran is economically and the more trouble they have with the sanctions, the more likely they are to sign, I think they’ve got it all wrong.

Jon Letman: You have family ties and a personal relationship with former president Khatami. You’ve interpreted for President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad at the U.N. And in September did voice-over work for an NBC interview with President Rouhani. What’s your sense of the new president?

Hooman Majd: From what I’ve seen with Rouhani, I think he’s very sincere. I know many people in his administration who were in the Khatami administration and have been politically sidelined for the last eight years. Netanyahu talks about a wolf in sheep’s clothing—I don’t think he’s a wolf in sheep’s clothing. I think he’s not a softy, not a pushover. He’s going to protect Iran and going to appear to be tough on certain issues. He’s going to demand that Iran’s national rights and sovereignty be respected by the world and particularly the United States. But I think he’s very sincere in saying the era of harsh rhetoric, which doesn’t do any good and is meaningless anyway at the end of the day, is over.

Jon Letman: Rouhani was educated in the U.K, right?

Hooman Majd: Partly. He got his PhD there. He’s spent time there. When he was a nuclear negotiator he spent a lot of time with foreign ministers from the European countries, had a good rapport. His English is very good—he understands virtually everything. I don’t think he’s very comfortable speaking it but he understands everything and can read and write it. I think he understands Western culture and I think that’s important.

In the Ahmadinejad administration, you had a person who had basically never left Iran ever until he became president. His first foreign trip was when he became president—and this was a man who was, at that point, almost 50 years old. A lot of the people surrounding him, whether they were advisors, cabinet ministers, or people in the administration, were the same.

Rouhani’s chief of staff went to George Washington University, got his PhD there, lived in America. His brother, who is one of his closest advisors, spent five years in New York. His foreign minister spent half his life in America—half his life. He was college student here and then worked for the Iranian government in New York.

So you have people who really understand the culture and I think that’s important. On the American side we don’t have people who understand the Iranian culture, so that may be a problem.

Jon Letman: When you heard about the Obama-Rouhani phone call, how did you feel?

Hooman Majd: I thought it was a really good move on both sides. I don’t know who exactly initiated it, but my own suspicion is that the idea came about in the private meeting between Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif and John Kerry. I think it was wise of Rouhani to accept the call. That’s not quite breaking the ice, but it’s a crack.

Jon Letman: When the Supreme Leader said there was something “inappropriate” about Rouhani’s September visit to the United States, was he referring to the Obama phone call?

Hooman Majd: Everyone assumes he was referring to the phone call because that’s the one thing that the Revolutionary Guards complained was not appropriate. I think it was a bone that he was throwing to the conservatives. For the hardliners, you don’t want to seem too eager to talk to the Americans. Khamenei didn’t want to be 100-percent of approving of Rouhani, in my opinion, because that would just be telling the hardliners they’re completely wrong. I think he likes to have the balance there between the various political groups in Iran.

Jon Letman: What role do you think the American public has in redefining our relationship with Iran?

Hooman Majd: They can have a role if they want to. When people write to their congressman that they don’t want to go to war in Syria, for example, and it’s running a hundred-to-one, I think it affects the president, it affects the Congress, it affects the Senate, it affects policy.

If people want to see a different relationship with Iran, they can be influential. Congress right now is not on the same page as this administration in terms of how to go about relations with Iran or how to deal with this nuclear issue. Congress is a lot more hawkish—“let’s have more sanctions, let’s be tougher, and if they don’t agree to what we say then we should bomb them.” If the American people feel that is something that should not be in the cards, then they can speak up and they can have an effect.

In a democracy such as ours people do have a voice. Whether they choose to use it or not is different—you can’t force people to—but we do have a voice.

Majd’s latest book: The Ministry of Guidance Invites You to Not Stay.

Jon Letman: And that’s where books like yours come in.

Hooman Majd: I hope so. It’s by writing articles and books and being on TV and talking that I try to give a viewpoint to an audience they may not have heard before. It’s not just me—there’s plenty of other very, very fine Iranian authors and journalists who do that all the time. Whether they’re pro-Islamic Republic or anti-Islamic Republic, I think the majority of the Iranian diaspora—other than a handful of crazies like the MEK (Mujahadin-e Khalq) and the other regime-change people—wants to see a peaceful negotiated end to the nuclear crisis so Iran can then move along.

One of the main things is this: When the Iranian regime doesn’t feel threatened by war, doesn’t feel threatened from the outside, it’s going to be easier for them to lighten up. It’s going to be easier for civil society in Iran to move forward and actually be engaged and try to bring about changes. As long as we’re constantly threatening them, it’s very easy for the government to be as repressive as it wants to be. I mean look at what happened after 9/11 in America. You can sell that stuff when people feel threatened. It’s harder to sell it when there’s complete peace.

Jon Letman: You told me about an American G.I. who served in Iraq and wrote to you expressing his appreciation for your first book. He said that he wished there had been a similar book about Iraq before the 2003 U.S. invasion, and that he hoped he would never be asked to fight a war in Iran.

Hooman Majd: What I try to do in my writing is to give an idea that there are people, there are humans there, and we affect them by what we do—including by imposing draconian sanctions on the population. We think we are just doing it to the government, but we are actually doing it to the people. We talk about war very casually sometimes: “oh, all options are on the table, if we have to blow up their nuclear sites, we’ll do it. We have to do it.” But we don’t think of the consequences, both for the Iranian people and in terms of the larger issue of whether we really want to be at war with this nation of 80 million people.

It’s important for Americans to know that, and I think what the G.I. said was important. We didn’t really know very much about Iraq. We didn’t even know there were Sunnis and Shias in Iraq when we went to war there.

The advantage with Iran is there has been a lot more literature on Iran in the last 10 years. There is a growing sense of understanding that there are real people there, and it’s not just a bunch of crazy mullahs shouting “Death to America” all the time.

Mr. Majd’s comments were edited for length and clarity.