Scattered across the globe, far from the staid conference rooms and policy salons of Washington, are some of the world’s premier experts on U.S. militarism. But they are neither the warzone refugees who have most borne its brunt nor the polished think tank professionals who increasingly populate the developing world’s capitals.

Scattered across the globe, far from the staid conference rooms and policy salons of Washington, are some of the world’s premier experts on U.S. militarism. But they are neither the warzone refugees who have most borne its brunt nor the polished think tank professionals who increasingly populate the developing world’s capitals.

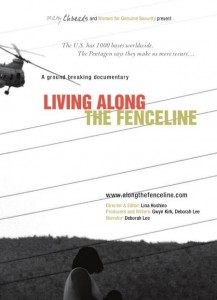

Rather, they are the people who dwell in the shadows of the estimated 1,000 U.S. military bases speckling the planet. As Deborah Lee of Women for Genuine Security (WGS) puts it at the beginning of Living along the Fenceline, they are experts in “the day-to-day issues of militarism.” More than anyone else, Lee says, they know “what it means to live with the military in your own backyard.” In times of war and peace alike, they confront the mundane corrosion of their communities by an omnipresent war machine.

Two new films—the WGS-produced Fenceline and Jam Docu Gangjeong, a controversial Korean documentary documenting the civil resistance to a planned naval base on the island of Jeju, South Korea—bring the stories of these accidental experts to life.

Witness to Empire

A crash course on the peripheries of the U.S. empire, Living along the Fenceline introduces seven women from distant corners of the world—from San Antonio to Seoul, from Guam to Puerto Rico—knit together by their witness to the often invisible costs of the global U.S. military footprint.

Diana Lopez, a Mexican-American teenager from the heavily military-dependent San Antonio, describes growing up in an environment where high school students who demur on band or gym class are required to enroll in ROTC instead. She recounts her efforts to expose the toxic pollution of Leon Creek, a popular swimming hole for local youth that was poisoned by runoff from a nearby air base, leading to a regional spike in cancer deaths. In Vieques, Puerto Rico—where the U.S. Navy displaced villagers decades ago to use the island for target practice—unexploded munitions and bomb scraps litter the landscape. Zaida Torres, who has lost several family members (including her daughter) to cancer, now provides aid to cancer patients and works to expose the deadly poisons that have lingered on the island long after the last bombs were dropped.

Elsewhere, in Korea, Okinawa, and the Philippines, we meet women who provide healthcare, education, and a voice for the victims of human trafficking and sexual assault that seem to materialize around every U.S. military installation. In Guam and Hawaii, the film introduces local activists working to preserve their environment and indigenous cultures from the military encroachment that perennially menaces both.

These short vignettes are succinct yet powerful case studies on the relationship of the U.S. military to the people who live in its shadow. The symptoms of this often abusive relationship—cancer, displacement, environmental ruin, sexual trafficking—are varied and often isolating. But the film’s greatest strength is the light it casts on the efforts of afflicted communities all over the world to share their stories and skills with each other. The resulting relationships lend strength to vulnerable local communities and make even parochial disputes between locals and bases into matters of international concern.

The women we meet in Living along the Fenceline are linked not merely by their troubles, but also by their activism—that silver lining that allows them to stitch together strong new solidarities from a fractured social fabric. “I get strength from other people,” says Sumi Park, who provides medical care to prostituted women and other townsfolk from the depressed village surrounding a U.S. military base outside Seoul. “I feel our hearts connect.”

Along the Shoreline

Where Fenceline captures a series of dispatches from a variety of locations, Jam Docu Gangjeong offers a variety of perspectives on a single flashpoint. The film, which was initially banned by the Korean Film Commission for its controversial subject matter, explores the campaign against the construction of a Korean naval facility at Gangjeong, a small fishing village on the pristine island of Jeju, South Korea. Many Korean activists contend that the base is designed for use by the United States as it repositions itself in East Asia.

The patchwork effort of eight different filmmakers, Gangjeong eschews the more direct narratives of Fenceline in favor of a collage of short films that tease out various angles on the standoff in Gangjeong. One of the more striking offerings is a short piece about two competing grocery stores in town—one for base supporters, one for opponents—that drives home the tensions, the absurdities even, that have emerged in the years since the Korean navy chose to make a home in Gangjeong. “Even the children may never recover,” laments one woman. “There are no words to describe the suffering [the base] has brought us.” Another short includes gripping footage of base resisters throwing themselves onto navy boats in an effort to stall construction, holding tight to the sides of the ships while men aboard blast them with powerful hoses.

But Jam Docu Gangjeong is not a simple protest anthology. In one particularly charming offering, a filmmaker gives cameras to a class of young children and invites them to take pictures of whatever they want to share. The kids flock to the beach and to the river, two sites mortally threatened by the base construction, and photograph rocks, waves, wildlife, construction sites, and each other. Back at school, they assemble the photos into a slideshow complete with sound effects, resulting in a moving (and adorable) ode to the natural treasures that may be lost to future generations. It’s a pleasant and graceful reminder of the love that underpins civil resistance movements as well as anger.

Other shorts following punk bands and anarchists opposed to the base (the focus of at least two of the film’s eight directors) fit less elegantly with the others, but they’re nothing if not interesting, and they lend a sense of humor to a years-old protest movement that would be hard-pressed to find its predicament amusing.

Ultimately Jam Docu Gangjeong is no crash course on the Gangjeong debate, and unfamiliar audiences will find parts of the film beyond their frame of reference (for example, references to the Korean army’s massacre of nearly a fifth of Jeju’s population in 1948, which is never really explained). But the patchwork production, in its own uneven way, shines a light on the truly human elements of the Gangjeong struggle, giving voice to activists as well as the villagers caught up in the struggle and ready for it to end. Perhaps most effectively, it communicates the enchanting properties of the rocky Gangjeong coast and its surrounding environs—a poignant reminder of what remains to be lost.

Unlike the more traditional experts on U.S. military affairs who vie for foundation dollars and media exposure, the accidental activists working to reduce the global U.S. military footprint would be happy to see their field reduced to obscurity. But as long the first group ignores the second—and as long as Washington circulates treatises on “force readiness” instead of genuine security—the league of accidental experts will continue to grow.