Long periods of general public apathy about reducing the threat of nuclear weapons via nuclear disarmament, such as the one we’ve been living through since the Nuclear Freeze movement, are not new to the United States. Writes Paul Boyer in a March 1984 article in the Journal of American History titled From Activism to Apathy: The American People and Nuclear Weapons, 1963-1980, nuclear activism also experienced a long drought in the years before the Nuclear Freeze movement. The situation parallels today. Boyer writes:

The most reassuring answer would be that the complacency was justified-that the nuclear threat diminished in those years.

Indeed, the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and SALT I went into force. But:

… when one turns from the realm of treaty making to the real world of nuclear weaponry, a different and bleaker picture emerges. In both the United States and the Soviet Union, nuclear weapons research, construction, and deployment went forward at a rapid clip after 1963. Taking advantage of the test ban treaty’s gaping loophole, both sides developed sophisticated techniques of underground testing. The United States conducted more tests in the five years after 1963 than in the five years before, some tests involving weapons fifty times the size of the Hiroshima bomb.

Not so different than today when nuclear “modernization” is a cover for new, improved nukes and the U.S. nuclear weapons budget projects out to one trillion over the next 30 years. Perhaps, in another post, we will outline the reasons Boyer provides. For now we will just cite one, which would be humorous if it weren’t so frustrating, before moving to the main point of this post.

… the nuclear apathy of these years was linked to the complexity and reassurance of nuclear strategy. … The public had only the dimmest awareness-analogous, perhaps, to a medieval peasant’s grasp of the theological concepts with which Thomas Aquinas wrestled-of the strategic theories debated within the walls of the institutes and think tanks.

A curiosity of that era, though, is that the Left more or less dropped nuclear disarmament from its agenda. Or, to put it more accurately, it was discarded in the transition from the Old Left to the New Left. To begin with, the Vietnam War, not to mention civil rights, sucked all the air out of the activism room. Boyer:

As media events, the war and the domestic turmoil it engendered had a vivid immediacy that the more abstract nuclear weapons issue could not begin to approximate.

… From that perspective the nuclear issue seems not so much to have been consciously set aside as pushed to the background. The Bomb was a potential menace; Vietnam was actuality.

But also disarmament was seen by the New Left as linked to the stodgy old, non-confrontational Old Left, in particular the most prominent anti-nuclear group, SANE (the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy). Boyer again:

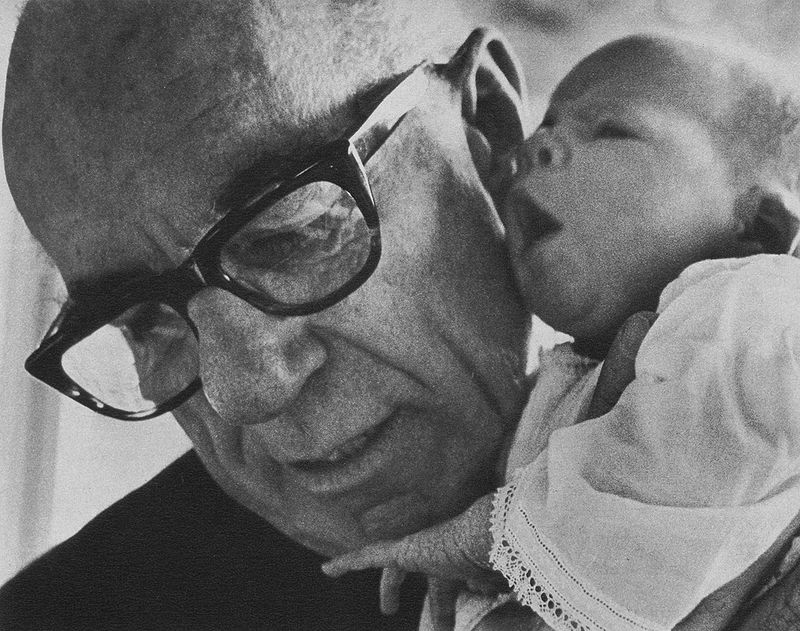

While some SANE directors, including cochairman [Dr. Benjamin] Spock, shifted entirely to the Vietnam issue, others strove to keep the antinuclear cause paramount.

“Understandable and even inevitable as it seems in retrospect,” continues Boyer,

… this process was distressing to the dwindling band of older activists who continued to focus on the nuclear threat. “From the long-range nuclear-age point of view,” wrote [one], “the most tragic feature of the war in Vietnam . . . is that preoccupation with this struggle is being allowed to stand in the way of the urgent business of making a far more devastating nuclear war less likely.”

Meanwhile

A closely related influence on post-1963 American nuclear attitudes was the emergence of the New Left, particularly the campus-based radical organization Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

… At the rhetorical level, the New Left talked a lot about nuclear weapons.

… Beyond the rhetoric, however, the New Left gave little serious attention to the nuclear issue and made little effort to sustain the thrust of the pre-1963 nuclear-disarmament movement. “It’s just a cliche” was the succinct comment of one Harvard activist on the claim that the New Left’s outlook was profoundly shaped by the looming shadow of the Bomb. Nuclear disarmament was doubtless implicit in the New Left’s vision, but one finds few specifics in the literature. When nuclear weapons are mentioned, they usually appear as part of an expose of the universities’ role in military research or of a more general indictment of capitalist society.

Yes, today, as well, disarmament activism sometimes seems like progressives’ — politically incorrect cliche alert! — ugly sister, trotted out occasionally for a walk around the block and then stashed away again in a back room.