Over the past year, the Trump administration has worked to craft a foreign policy aimed at putting America first and reclaiming center stage globally. It has even given this approach a name: the “Donroe Doctrine,” which, like the Monroe Doctrine, purports to reassert American dominance in the Western hemisphere. The label suggests continuity with earlier strategic frameworks, but the reality is different. Unlike the Monroe Doctrine, which articulated boundaries and imposed strategic constraints, the “Donroe Doctrine” offers no coherent vision of U.S. leadership. What emerges instead is foreign policy as performance, driven by spectacle and attention rather than strategy or governance.

Nowhere is this approach more visible than in the administration’s handling of Greenland.

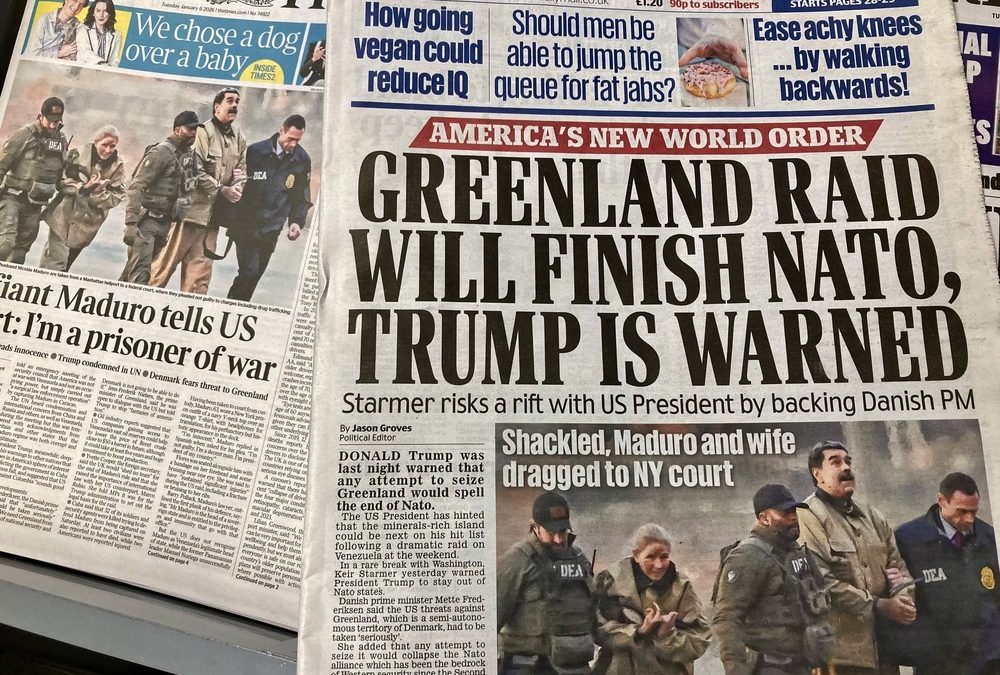

For years, President Trump has floated the idea of purchasing Greenland from Denmark, at times framing the island as a real-estate transaction and at others implying that U.S. control could be asserted through pressure or force. When Denmark rejected the proposal, the episode produced headlines but no diplomatic framework, no articulated strategy, and no consequences beyond the news cycle.

That posture was reinforced during mid-January White House meetings with Danish and Greenlandic officials, where the president asserted that the United States “needs” Greenland, openly questioned Denmark’s ability to defend the island against Russia or China, and offered little more than vague assurances that “something will work out” in lieu of any articulated plan for its future governance.

More troubling are repeated insinuations that Greenland could ultimately be taken by military force, rhetoric now reinforced by the Trump administration’s willingness to brandish punitive tariffs and economic pressure against close allies as tools of leverage. Such rhetoric undermines the peace and stability that have defined the Euro-Atlantic space for more than seven decades. It erodes the basic assumption that NATO allies do not threaten one another’s sovereignty. Only a few years ago, the idea that Denmark might feel compelled to reinforce troop deployments in Greenland in response to a threat from the United States would have been dismissed as implausible. Today, it is discussed not because of Russian aggression, but because of American rhetoric. That alone should give policymakers on both sides of the aisle pause.

Claims that Greenland faces an imminent takeover by Russia or China do not withstand scrutiny. Greenland is part of the Kingdom of Denmark, a NATO member protected by Article 5 of the alliance’s charter. The United States already maintains a military presence and extensive access through existing defense agreements. Russian and Chinese activity in the Arctic has focused on investment and research, not territorial conquest. Framing Greenland as a looming takeover scenario reflects threat inflation rather than strategic realism.

Public opinion further underscores the disconnect. A Reuters/Ipsos poll found that only about 17 percent of Americans support efforts to acquire Greenland, while nearly half oppose them. Far from reflecting popular will, the proposal reads less like strategy than a top-down fixation on notching a symbolic “win,” untethered from serious strategic purpose.

Venezuela follows a similar pattern. The arrest of Nicolás Maduro unfolded with dramatic speed and dominated headlines, but it was followed by little clarity on governance, stabilization, or reconstruction. Initial suggestions that the United States might govern Venezuela were quickly walked back. Early assumptions that private-sector oil investment would anchor recovery proved thin. As with Greenland, aspiration was detached from strategic and political realities.

The same dynamic was visible in the December 2025 Christmas Day bombing in Nigeria framed in part as protecting “Christians,” a moment that briefly dominated the news cycle but has since yielded little publicly articulated policy clarity or strategic follow-through.

Greenland, however, carries far higher stakes. Unlike symbolic provocations that dissipate once headlines fade, Greenland implicates alliance credibility, territorial sovereignty, and the foundations of the postwar Euro-Atlantic order. The substitution of spectacle for strategy here is not merely unserious, but destabilizing.

After seeking to castigate and isolate Russia for its violations of international law and territorial integrity in Ukraine, the United States now risks hollowing out its own normative authority by invoking similar logic in Greenland and Venezuela, weakening the very rules-based order it claims to defend. If territorial coercion can be rationalized by asserted necessity, strategic interest, or power asymmetry when exercised by Washington, there is no credible basis on which to insist that China refrain from applying the same logic to Taiwan, or that Serbia permanently abandon claims over Kosovo. The danger is not false equivalence, but precedent. Once the prohibition on territorial coercion is selectively enforced, it ceases to function as a binding rule and becomes little more than rhetorical convenience.

What emerges is a model of foreign policy driven by spectacle and bravado rather than strategy, one that prioritizes image and headline value over advantage and risks eroding the very liberal international order the United States once built and defended, an erosion that seemingly is not accidental.

Ironically, these actions stand in stark contradiction to the administration’s own National Security Strategy, which warns against ill-defined objectives and aspirational ends untethered from realistic planning, even as practice has moved in the opposite direction. Allies adjust, credibility erodes, and influence thins, creating openings for America’s adversaries. This dynamic is compounded by the hollowing out of core soft-power tools, including cuts to USAID and other foreign assistance programs, the erosion of the diplomatic corps, and reductions in public diplomacy and international broadcasting, precisely the instruments needed to convert power into lasting influence.

When foreign policy becomes performance rather than policy, the applause fades, but the strategic costs endure. None of this makes America safer, stronger, or more prosperous.