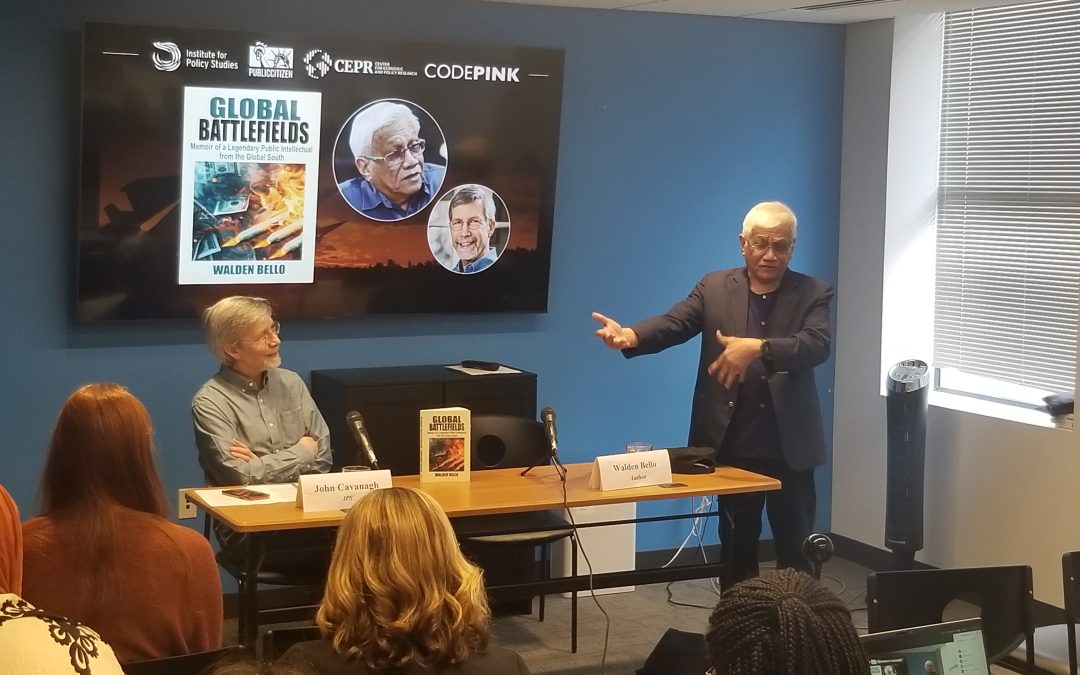

A great political memoir uses an individual story to humanize the dilemmas of fighting to remake the whole world. Such is the case with Walden Bello’s compelling new memoir, Global Battlefields.

Throughout the book Bello dissects a central tension in his political life: the dance of ideas and action. Bello makes this theme clear through his repeated citation (at least four times by my count) of Karl Marx’s declaration in Theses on Feuerbach: “Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.”

The author of 25 books (mostly about international political economy), the holder of a PhD in Sociology, and a professor who has taught in universities around the world, Bello is undeniably a philosopher in Marx’s sense. He respects the value of intellectual work. For him, the key phrase in Marx’s quote, the one that challenges the reader is: “hitherto.” The problem is not trying to understand the world. The problem arises when that step is the last step.

And since the day in April 1970 when he leapt into the middle of a skirmish between police and protestors, Walden Bello has embodied the praxis demanded in Marx’s quote.

“Always Be Part of a Movement…”

For those unfamiliar with him, Walden Bello is a sociologist, activist, former Filipino Congressman, writer, strategist, professor, and teacher. In his native Philippines, he is best known for his decades of anti-authoritarian activism, his almost eight years serving in the Filipino House of Representatives, and his runs for the Senate and the Vice Presidency. Globally, Walden’s name evokes his long work with the activist policy organization Focus on the Global South, as well as his participation in global struggles against neoliberalism and its many institutional drivers.

In Global Battlefields, Bello recounts his life as a political figure, mostly skipping over his childhood and youth. While the book hews to the cerebral, it is not a cold work. At times, I laughed out loud, such as when Bello recounts his increasingly strained efforts to avoid being photographed with Imelda Marcos while both served in the Filipino House of Representatives.

There are also exciting anecdotes, such as the story of how, over a period of three years, he and a small team of activists regularly snuck into the World Bank’s Washington D.C. headquarters to copy secret documents demonstrating the Bank’s role in propping up the Marcos regime. I also found the book quite moving. This was especially the case near the end, when Bello swings away from political reflections to offer a very moving chapter about his heartbreaking marriage with Ko Thongsila, who died of cancer five years into their marriage.

At the same time, this is also a memoir that contains a reprint of several pages from an academic article about the material/political/social conditions faced by, and the grand strategies of, the Philippine Marxist insurgents of the 1970s. In other words, much of the book consists of analytical reflections on various policy and political quandaries. It is a book that insists on a left that engages in thoughtful self-critique. As he declares, a person should always be “part of a movement, part of progressive organizations . . . but not uncritically so.”

“… But Not Uncritically.”

In particular, Bello insists that the left needs good analysis to have solid strategy.

Personally, I found one of the most fascinating examples of this philosophy right at the start. As a PhD candidate in the early 1970s, Bello decided to head to Chile to witness the hopeful chaos then wracking the country. In 1970, a coalition of leftist parties eked out an electoral victory, allowing democratic socialist Salvador Allende’s ascent to the presidency.

Recounting his time in Chile, Bello chides a frequently heard leftist view: that U.S. interventionism represents almost the only important force in world affairs. For Chile, this often means the September 11, 1973 coup is simply told as the CIA and Nixon overthrowing the government.

Instead, Bello points to a more complicated story with much local agency. He dissects the Chilean left’s misunderstandings of the country’s bourgeoisie, arguing that it blinded the left to a real and growing threat from a major social sector. While the U.S. certainly played an important role in the coup, Bello urges us to understand “internal dynamics . . . that the Chilean elites were able to connect with middle-class voters terrified by the prospects of poor sectors rising up.”

Bello continues this sharp analysis throughout the book. A significant portion of the work explores his decades of fighting for social justice in his native Philippines. Bello names the villains — the Marcos family, Duterte, selfish elites, and more. But he also tries to understand the left’s failures, where they stemmed mainly from forces outside their control and where internal dynamics played a role.

On the global justice front, Bello finds room for optimism. He recounts the glory days of mass protests against international financial institutions — including his memories of the Battle of Seattle — as well as his participation in actions against the U.S.-led War on Terror. Bello celebrates that the left “said bullshit and fought back, and now, thirty years later, the WTO is paralyzed . . . and neoliberalism, while still institutionalized, has been intellectually discredited.”

He also reintroduces readers to his concept of “deglobalization,” a vision of a different world political economy based on local production and democratic governance. Helpfully, Bello digs into how “deglobalization” has also become, in a way, a mantra of the ethnonationalist right across the globe, while clearly laying out the vast differences between left and right visions.

Morality and Pragmatism

Throughout it all, Bello argues for keeping morality and practicality in constant, uneasy conversation.

Looking to his own time in the Filipino government, Bello digs into how he thought through when to compromise and when to stick to principle. He lauds the potential of holding state power, noting his role in helping pass legislation upholding (some) reproductive justice measures, his fight for agrarian reform, and times helping the Philippines maintain a principled anti-imperial stance in foreign relations.

As much as he chose pragmatism however, Bello does not scoff at high principle.

After all, he left Congress of his own accord, before his term expired. In retelling this story, Bello argues that the defense of democratic norms is vital for winning social justice. His decision to exit Congress came because of his party’s continued support for an administration involved in high-level corruption.

Yet even in this act, politics mix with moralism. For the left to win widespread support requires sending clear signals to voters about who you are. And as Bello explains, “at a time when people have become so cynical about visions and programs . . . the distinguishing mark of a true progressive holding public office is . . . ethical behavior.”

The book closes with Bello posing questions about the future of the left and global politics. He is certainly not optimistic, but nor does he wallow in pessimism. Rather, he gives us all a challenge: to simultaneously be philosophers interpreting the world and organizers fighting to change it.

Strong lessons for trying times.