Damir Niksic, If I Wasn’t Muslim. 2004.

Damir Niksic, a conceptual artist from Bosnia Herzegovina, is best known for his notorious 2005 video installation If I Wasn’t Muslim. Performing a sarcastic song about being a Bosnian Muslim surrounded by Christian neighbors, Niksic provides a painful, yet humorous analysis of ongoing hostile tendencies against Muslim populations. The song is set to the music of “If I Were a Rich Man,” from Fiddler on the Roof, a Broadway musical about the removal of Jews from Tsarist Russia that mirrors the looming horrors of WWII. During the Yugoslav Wars, Serbian special forces captured Muslims throughout the region, tortured them, forced them to work as slaves, sent them to concentration camps, and sometimes executed them as well. The parallel Niksic proposes is an excruciating one.

Offering a highly explosive mix of video, installation and performance art, Damir Niksic addresses challenging but heartfelt political issues that can be traced along the lines that separate Eastern Europe from the West. Other projects include The Boogeyland Reservation from 2009, a performance piece that invites the audience to cross borders — not only geographical, but also mental and cultural ones within their own society. Bosnian Flight, from 2007, is a video about the motives and reasons behind exodus and migration filmed at the site of the destroyed Aziziya mosque in Brezovo Polje, Northern Bosnia.

NIELS VAN TOMME: One of your recent projects is GHETTOVILION (not just another, but “the Other” pavilion), a virtual pavilion established in the framework of the 53rd Venice Biennial Art Exhibition (Making Worlds). It is dedicated to “the Other” art scene of ethnic minorities and the Fourth World. Why did you feel the need to represent these people in the context of this global art event?

DAMIR NIKSIC: Europe is still facing problems with its ever-growing ghettos, with ethnic minorities and fourth world nations such as the Roma population. Unlike in the United States, European national cultural politics and art institutions rarely deal with ethnic minorities as equals, with their cultures, or with the notion of the ghetto in general. They may support ethno-art or folk art, but not contemporary art or young creative individuals. This strategy only helps to reinforce old stereotypes and conservative powers, and leads to further cultural segregation, “othering,” and alienation. There’s an entire population that is marginalized and excluded from many state-supported cultural events, financed by the taxpayer’s money. This population is perceived as cheap labor, or the reserve army of labor. I’m talking about immigrants and other minorities. We don’t see them represented in museums of contemporary art. We might even laugh at that idea. Their problems and their voices are absent. They’re living a different reality that may not be of interest to everyone, but it’s certainly interesting to them. And they’re paying taxes, which means they ultimately contribute to the financing of the art institutions they’re excluded from.

Since Venice is the very birthplace of the term ghetto and since the Biennial is conceived as an international platform of national pavilions, there must be a space there for this population. In a united Europe, the ghetto must be presented, represented, or, should I say, self-represented.

NIELS VAN TOMME: Not only in this one, but also in many other projects of yours, you take up the cause of the underdog and the systematically excluded, or to say it with your own words: of the “loser.” What can we learn from identifying with such marginal positions?

DAMIR NIKSIC: An artist has to give voice to those without a voice. I’m not only identifying with “losers,” I testify about difficult positions, about the social reality of people who are being stigmatized and made into losers, who are supposed to learn their proper place in European societies.

Somebody has to be a loser in order for others to do well. Today it’s not the proletariat, a social class within the nation. It is “the other,” the immigrants from Asia, Africa, from other parts of Europe, East or South. In some way I feel very close to all of these groups. I’m a Slavic-speaking Muslim from the Balkans, from Southeastern Europe, so I can identify with all these people. I studied in the United States, I hold an MFA and MA in art history but I’m profiled, or classified, according to old European stereotypes and expected to learn my place in society. That’s very frustrating.

Damir Niksic, Bosnian Flight. 2005.

NIELS VAN TOMME: Being a Bosnian artist of Muslim descent, you travel extensively throughout Europe and the United States and your work is shown internationally. Nevertheless, you position yourself as an outsider. I’m wondering how deeply rooted that experience of being “other” is?

DAMIR NIKSIC: Europe is full of “others.” There are many languages and many dialects, so you can easily be recognized as other, or as different. As soon as I start speaking in my native language, anyone from Serbia or Croatia will say that I am from Sarajevo, Bosnia, which implies many other things. My name is not a typical Muslim name, my last name could also be Serbian, Croat, or Bosnian, but my slang or absence of slang raises many questions. Not being able to speak German, or Italian, or any other language perfectly makes it difficult to participate or to integrate in European societies. I’m trying to survive with English, trying to be a part of that first generation of Europeans who participate in creating a European multicultural identity, a free and open society, which is also the legacy of my city, the city of Sarajevo. I’m trying to establish dialogues, to embrace a cosmopolitan spirit, so for local nationalists I’m also “the other.”

NIELS VAN TOMME: You often use embarrassing and sarcastic humor to confront your audience with their own racist prejudices and privileged position. What do you anticipate from such direct confrontation?

DAMIR NIKSIC: I expect dialogue and a higher level of awareness. I expect awakening, learning about different points of view, experiences, interests, getting to know our neighbors, learning about their stories and their realities. I use humor because my message might sound somewhat pathetic otherwise. The sarcastic black humor I bring into play communicates also my awareness about my position. I’m aware about the way my work can be perceived by people who are not familiar with the topics it addresses, or by those who are too closely related to the topics and its stereotypes. So I’m trying to destroy the entire thing, the societal construction, and reach for the hearts and minds of people by entering through the door of absurdity. This must necessarily lead toward common sense, because our mind is automatically looking for it, always rationalizing our experiences. I think that’s a much better strategy than appealing directly to common sense. Humor makes it more self-aware and self-critical.

NIELS VAN TOMME: Would you consider your work political art? I’m asking this because there always seems to be a second layer emerging from it, which prevents it from merely illustrating a political issue. For example, your 2008 video The Immigrant Song is simultaneously a comment on the West’s migration policy and the curator’s decision to display the artwork in an exhibition context. It seems that you are more invested in Jean-Luc Godard’s claim of “not making political films, but rather making films politically”?

Damir Niksic, Europe Has a Serious Problem. 2007.

DAMIR NIKSIC: Democracy made everything a political issue, just as religion makes everything a spiritual one. Some regimes turned reasoning, mere thinking, the processing of thoughts, into a political activity, persecuting common sense. I grew up in Socialist Yugoslavia where our lives were part of the huge socialist economic experiment, believing in the coming of communism, the disappearance of the state, and a better classless society. We all live and think politically. We are trained to self-censor: we constantly double-check our thoughts and adjust them to the current regime or ideology. That is how we grew up. Ideology is political. Believing in a better society, in democracy, is an ideology. We all act according to our beliefs, our ideological, political or philosophical positions, and that’s all political. We live politically. Even not being political is a political decision. So one can’t escape it. That’s the name of the game.

Art needs to create a parallel world, one that’s more absurd than the political one. The art map of the world should be different than the political map of the world. The South should be on the top, and the global art centers should be in other cities, dictated by soul, juice, and creativity, not by money. Money helps, but it should not dictate everything.

In the context of democracy, of human and civil rights, when you sing about justice and injustice, when you sing the blues, a song about freedom, about your dreams, the promised land — it is political, it’s not spiritual because democracy, or politicians, took that responsibility and promised us paradise. So I appeal to such democratic and liberal intellect.

There’s a political philosophy in my works. It’s a “pathetic appeal” to those individuals who like to see it from a different perspective, in this case mine, or that of people like me. I am the voice of those people and I’m sending that message without any hope or expectations. I don’t expect any change. I’m just telling it as it is. It’s acid, bitter, and I’m doing it just for the record, so that people can’t say: “I didn’t know it.” Now you know. Now I know that you know that I know that you know.

That’s communication, a political thing, between two or more human consciousnesses. Otherwise it would be a lament to God, like in spiritual songs, or other folk music singing about destiny, bad luck, suffering, poverty, such as Roma music or sevdah in Bosnia. My work is political because it is directed toward certain recipients, exclusively humans, trying to raise awareness about certain phenomena. I don’t ask them for help or understanding. Usually those people can’t even help themselves in the context of their own societies. But they should know they are not the only, or the biggest losers in the world. So I’m anticipating they will wake up in their own reality and realize it’s not so bad after all.

NIELS VAN TOMME: You currently live in Sweden. How different is it to be a Muslim over there than it is in Bosnia Herzegovina?

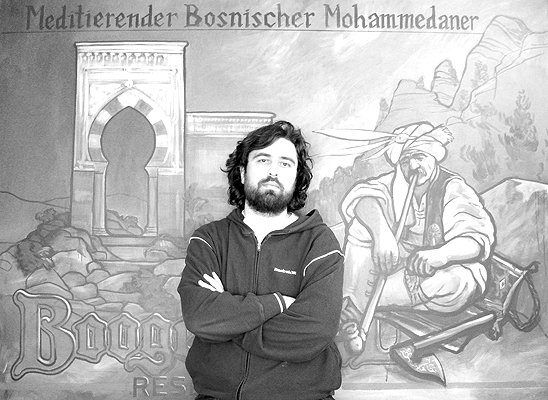

Damir Niksic, Meditierender Bosnischer Mohammedaner, 2009.

DAMIR NIKSIC: Bosnia Herzegovina is a very unfortunate country. I call it the South-European Republic. There is apartheid in some parts. There is real segregation, Jim Crow laws. KKK, ghettos, reservations, you name it. It’s a very sad country. It’s much better to be a minority somewhere else. It’s much better to have other Europeans as “masters.” The South is a bad place for “others,” there’s too much violence and animosity.

NIELS VAN TOMME: Although the Bosnian War ended 15 years ago, many political, social, and ethnic conflicts remain unresolved. How do you see the future of your home country?

DAMIR NIKSIC: I’m struggling to see any. I really think it’s a lost cause. Bad leadership and corruption brought a huge deal of disappointment, desperation, and disorientation.

NIELS VAN TOMME: Are you currently working on any new projects?

DAMIR NIKSIC: Many new projects — as always. I’m preparing a book about the “European Dream,” called Caravan of Dreams. It’s about immigrants, expectations, disappointments, etc. The Swedish arts grant committee Konstnärsnämnden gave me a grant for that. And I’m also developing some sort of pseudo-stand up comedy show, as you can see on my website. I’m trying to explain some issues and points of view as directly as possible, with a witness protection program technique, changed voice, and hidden face.