On July 4—just over a week after the U.S. Supreme Court, in a ruling that was in equal measures unsurprising and tragic, overturned federal abortion rights—Chile’s Constitutional Convention finalized and submitted a draft of a new Magna Carta. Whether it will be implemented depends on the results of an upcoming referendum on September 4.

The proposed Chilean constitution is the product of year-long deliberations by a popularly elected citizens’ assembly, comprised mostly of left-leaning and independent delegates. It foregrounds progressive principles such as plurinationalism, gender equality, decentralization, and sustainability, as well as the “social” role of the Chilean state in areas including education and healthcare.

In these and other ways, it represents a firm rebuke—and an effort to undo at least some of the worst effects—of the elite-dominated neoliberal system imposed at gunpoint during the Washington-backed Augusto Pinochet regime (1973-1990). The current constitution was ratified in a sham, regime-managed referendum in 1980 and largely maintained after the return of electoral democracy.

At precisely the moment when Chile is navigating the hopeful but potentially fraught path of reform, and inspiring progressive movements around the world in the process, the U.S. constitutional order is suffering a profound crisis of legitimacy. Indeed, the U.S. Constitution’s supposedly sacrosanct “guardian”—the Supreme Court—has revealed itself in its current incarnation to be in thrall to the right and hostile toward the very liberal-democratic values it claims to safeguard.

What can we learn by juxtaposing the distinct constitutional processes unfolding in these two longstanding hemispheric allies?

U.S. Politics and the Myth of Apolitical Order

Though the U.S. public is accustomed to (if not entirely favorable toward) the many eccentricities that permeate the country’s institutional framework, like the Electoral College, similar arrangements are, to put it gently, far from the norm internationally.

Indeed, in many respects, the United States is an aberration vis-à-vis its peers. Attempts to explain to foreign audiences the existence of such democratic deficits within the world’s self-styled leading democracy typically elicit a mixture of confusion, disbelief, and consternation.

Especially telling examples include the fact that residents of the national capital are denied federal legislative representation, the last two Republican presidents entered office despite losing the popular vote, and unelected, lifetime-appointed justices—who claim nonpartisanship but were nominated precisely to promote a partisan agenda—have recently gone on a spree of striking down popular legislation based on highly idiosyncratic, minoritarian, and dubious legal “philosophies.”

A common justification for the U.S. constitutional order is the oft-repeated notion that the Court and Constitution exist “above politics” and the morass of ideological conflict.

Perhaps the most common reference point for this sentiment is Chief Justice John Roberts’ assertion, during his 2005 confirmation hearing, “that it’s my job to call balls and strikes, and not to pitch or bat.” In practice, of course, the Roberts-led court has done a tremendous amount of hyper-partisan “pitching” and “batting”—as evidenced not only by the overturning of Roe v. Wade, but also, inter alia, recurring pro-business and anti-environmental rulings, as well as its systematic failure to protect the very voting rights that are at the heart of the liberal-democratic order that the Court ostensibly exists to defend.

Indeed, though it has long weaponized the phrase “judicial activism” against its opponents, the right has spared no effort in its attempts to reshape the country’s political-legal institutions in its own image and constrain the popular will.

Right-wing rhetoric aside, the truest believers in the misguided idea of an apolitical Supreme Court appear to be centrist elites such as Vice President Kamala Harris, as evidenced by the curious response she provided when asked during a recent interview whether the Democratic Party had “fail[ed]” by neglecting to pass (or even making a serious attempt to pass) pro-choice legislation during the preceding five decades.

Invoking the quixotic notion that Americans inhabit a post-political sphere in which key rights can be taken for granted, she stated: “I do believe that we should have rightly believed, but we certainly believed that certain issues are just settled.”

That the Biden administration and Democratic Party leadership have responded in such a tepid and unassured fashion to the overturning of Roe v. Wade—this, despite the fact that a draft of the decision was released over two months ago, and that it has long been the declared mission of much of the U.S. right to end abortion rights through legal and/or other means—can be explained in part due to ideology.

However, such a dangerous passivity also flows naturally from the wrongheaded idea—which is certainly not shared by their right-wing adversaries—that courts are neutral, apolitical spaces peopled by technocratic elites who exist merely to dispassionately apply the rules, and never to participate in the making of rules, or draw from their own ideological leanings to interpret and enforce particular understandings of them.

Contrary to the understandings of the Democratic Party leadership, Chile’s upcoming constitutional referendum provides a clear reminder of what is at stake vis-à-vis the establishment and the functioning of legal, political, and institutional orders.

A Chilean Path to Social Democracy?

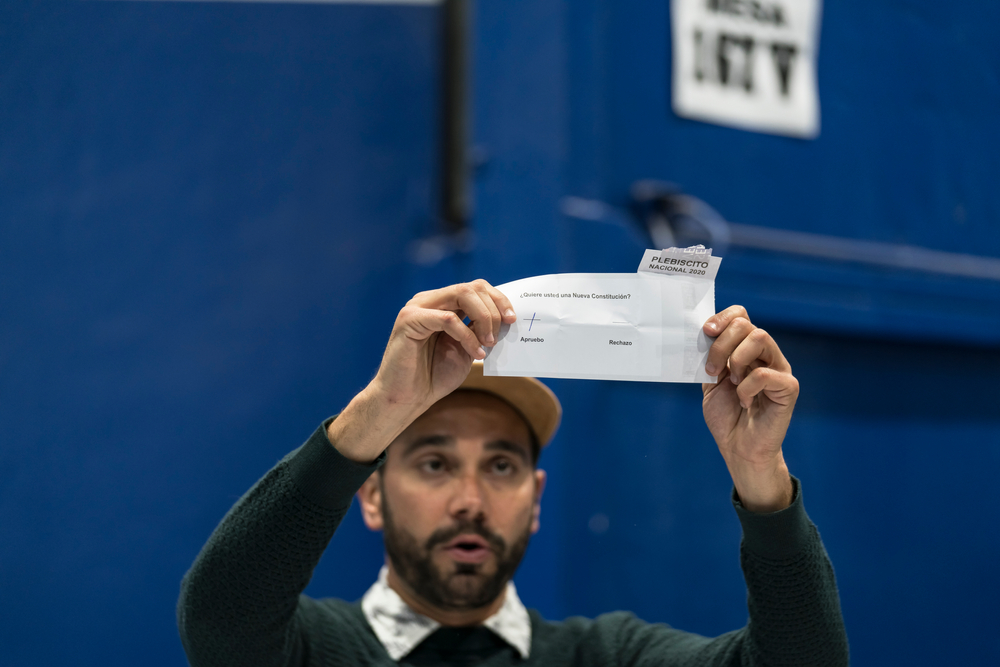

During the October 2020 national plebiscite, nearly 80 percent of Chileans voted in favor both of drafting a new constitution and of awarding authority to do so to a citizens’ assembly, whose members were chosen by a subsequent popular vote.

Only 21 percent of voters opted for the elite-friendly alternative of placing drafting authority in the hands of a mixed assembly, to be comprised in equal measures of elected delegates and members of congress. The vast majority of Chileans thus chose to express discontent with the status-quo constitutional order, open the door for the implementation of a new one, and put an alternative on the table that responded to the demands, hopes, and desires of everyday citizens as opposed to entrenched political interests.

To be sure, Chile’s path to a new constitution—and a fairer, more egalitarian, and more democratic society—confronts many obstacles.

Traditional Chilean elites and media, true to form, have engaged in an unceasing opposition campaign to paint the draft constitution not as a potential threat to their own financial interests and privileges, but as an unwieldy, bloated, and cost-insensitive Magna Carta that enshrines invented economic, social, and cultural rights that are of little interest to everyday Chileans. As one skeptical analyst commented, “The result is by turns silly and by others deeply concerning for Chile’s long-term political and economic health.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, recent polling indicates that a narrow majority would reject the new constitution.

The same narrative predominates in mainstream circles abroad. For The Economist, the draft represents a “fiscally irresponsible left-wing wish list” (and, with 388 articles, is “absurdly long”). Leaving little to imagination, the accompanying image consists of a roll of toilet paper that features lines of text and an official seal.

Even a more sympathetic assessment by The Washington Post refers to Chile’s “woke constitution.” This despite the fact that some of the more “radical” proposals, such as a partial nationalization of the highly lucrative mining industry, were not incorporated into the final draft. Also, even the centrist Christian Democratic Party has voiced support for the document.

Alarmist oppositional rhetoric aside, the upcoming ratification vote presents several valid reasons for concern—beyond the standard caveat that any constitution-writing process requires grappling with foundational political, social, economic, and cultural questions about which there is often a lack of consensus.

A guarantee of housing in the Chilean constitution may satisfy a key progressive demand. Yet words on a page do not necessarily translate into a concrete enjoyment of the stated rights. Indeed, Brazil’s 1988 constitution, similarly promulgated to replace an authoritarian-born predecessor, also guarantees a right to housing (along with food, assistance for those in poverty, and so on), though in practice homelessness, food insecurity, and economic hardship continue unabated.

By itself, and without accompanying legislation, the new constitution—if approved—would be only the first step in the inauguration of the new social order for which so many Chileans have struggled and sacrificed. Especially given the divided status of Chile’s current congress, and with a raucous right-wing opposition striving to sabotage the entire endeavor, there is ample opportunity for disillusionment to supplant the optimistic spirit that led to this hopeful process.

Beyond Apolitical Politics

Whatever the outcome, the Chilean experience demonstrates that there is no respite from politics. In the United States, by contrast, conservative jurists tout the “original intent” of the Framers in dispassionately applying their supposedly timeless and universal wisdom to situations and contexts that would have been completely foreign to them. Meanwhile, Harris has called on those opposed to the overturning of Roe v. Wade to elect a “pro-choice Congress,” but without offering concrete solutions to the voter-suppression tactics and pernicious forms of gerrymandering that render such an outcome increasingly unlikely in the first place (with the acquiescence, of course, of the Court itself).

The Chilean constitutional process, whatever its limitations and flaws, is more honest (not to mention more democratic). For it reveals the extent to which constitutions are not just legal but also political documents that reflect distinct ideological positions and worldviews. Accordingly, they are always open to political contestation.

Contrasted with rule by fiat by a Supreme Court that values gun ownership over bodily autonomy (or personal safety), the idea of elected citizens deliberating and arguing over what kind of constitution and court system they want—as messy as the process may be—seems an appealing alternative.