For the past couple of years, Robert Burns of the Associated Press has been chronicling what he describes as the “deliberate violations of safety rules, failures of inspections,” and “breakdowns in training” of the United States nuclear missile force. He’s also found “evidence that the men and women who operate the missiles from underground command posts are suffering burnout.”

In what may be the biggest such scandal in Air Force history, 34 officers entrusted with land-based nuclear missiles have been pulled off the job for alleged involvement in a cheating ring that officials say was uncovered during a drug probe.

The top command has seen enough. “Dissatisfaction among the officers responsible for operating intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs, is not new, but it appears to be grabbing the attention of more senior Pentagon leaders, including Hagel and Air Force Secretary Deborah Lee James, who was sworn in Friday as the service’s top civilian official,” reported Burns on January 25.

Three days earlier, Burns’s colleague at the Associated Press, James MacPherson wrote:

Air Force Secretary Deborah Lee James visited F.E. Warren Air Force Base at Cheyenne, Wyo., Tuesday and Malmstrom Air Force Base in Great Falls, Mont., Tuesday and earlier Wednesday.

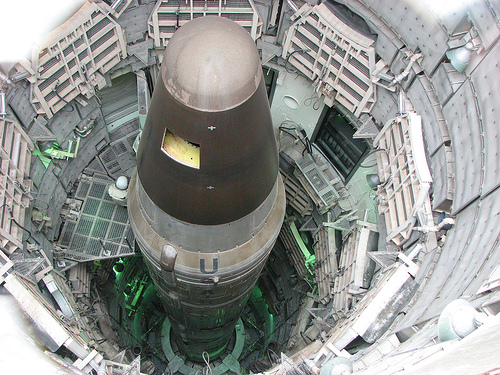

The fact-finding tour, in response to cheating and drug scandals the Air Force announced last week as well as a string of other missteps The Associated Press revealed in 2013, is aimed at finding the breadth of problems within the force that operates the nation’s Minuteman 3 nuclear missiles.

… In Cheyenne Tuesday, James addressed a large crowd at the F.E. Warren base and also met with airmen in smaller sessions, the Wyoming Tribune Eagle reported. She said she heard concerns about the career implications of missing an answer or two on the command’s monthly tests.

“So I’m interested to explore further whether or not we are placing the right emphasis on these monthly tests, as well as the simulations and the outside inspections,” James said.

Air Force Secretary James seems to be echoing some of the same concerns about overemphasis on testing that many have about our nation’s elementary and secondary schools. She also said, MacPherson reported, that she “picked up on some ‘morale issues’ but remains confident about the capability of the nation’s nuclear forces.”

Sharing the morale concerns, as Burns himself reported on January 25,

… Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel is searching for the root causes of recent Air Force missteps but also for ways to make the nuclear warrior’s job more attractive at a time when the military has turned its attention away from such weapons.

Nuclear missile duty has lost its luster in an era dominated by other security threats. It’s rarely the career path of first choice for young officers. And yet Hagel and others say it remains important to U.S. national security. … And so it is worrisome, Hagel said, to realize that some of those same airmen may use drugs, cheat on their proficiency tests and have engaged in other dangerous misbehaviors.

… “We know that something is wrong,” he said, and it includes what some call an attitude problem inside the force. … Hagel wondered out loud Friday whether the remoteness of these ICBM locations might be a factor in dampening morale among missile operators.

“Do they get bored?” he asked.

True, but as I’ve speculated before, it may not just be morale, but morality. That is, they may be experiencing the precursor to PTSD ― concerns about what might happen if they’re called upon to initiate a launch sequence which would result in the deaths of anywhere from tens of thousands to millions. But that’s probably giving them too much credit. Burns quoted Dana E. Struckman, a retired Air Force colonel who served as a Minuteman 3 missile squadron commander: “What the young men and women on the crew force would like to see is, this is a viable career path for me even if I’m not the star of the squadron.” Burns explains:

ICBM duty may never have been glamorous, but in the years after the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991 it appears to have become less attractive as the Air Force shifted some of its focus to wars in the Mideast and emerging threats like cyberwarfare.

Solutions?

One repair tool that James and Hagel might choose is incentive pay or other extra benefits for the young officers who do as many as eight 24-hour shifts per month in the underground command.

Of course, that does little to address the underlying issue: the perceived irrelevance of their work. Maybe it’s time to admit that nuclear weapons themselves have become irrelevant. Their principal proponents of nuclear weapons are a few hawks, including a decreasing number of generals; the government agencies that administer and execute the nuclear-weapons program (the Department of Energy and the National Nuclear Security Administration); nuclear laboratories such as Los Alamos, Sandia, and Oak Ridge, and the manufacturing facility Pantex, and the corporations that manage them; and, critically, the members of congress who benefit from contributions from the industry and the jobs (however few in number) that the facilities bring to their districts.

Other than that, many Americans reflexively support deterrence, the logic of which is hard to refute, on principle. But most don’t want to know about or have to think about nuclear weapons. They just want them to remain on the shelf. But as long as the missile launch force feels like it’s been shelved, or is serving in the equivalent of armed forces Siberia, its members will look longingly at those U.S. Air Force commands where they perceive the action ― and the future ― to be.