The logic of deterrence is irrefutable to most, especially when applied to nuclear weapons. Nevertheless, its effectiveness is questioned by everyone from disarmament activists to revisionist historians ― some of whom maintain that other factors constrained the United States and the U.S.S.R. from attacking each other during the Cold War ― to nuclear-weapons advocates. Among the last are those who assert that deterrence is of little value against a state such as Iran in the event that it were to acquire nuclear weapons. Apocalyptic clerics, they allege, would supposedly martyr their country rather than back down from a nuclear standoff, thus necessitating, at some point, a preemptive strike.

The validity of deterrence aside, the time is long overdue to reevaluate how it’s implemented. In an op-ed for the New York Times titled Ending Nuclear Overkill, Benjamin H. Friedman and Christopher A. Preble write:

Over 20 years after the Cold War, America’s nuclear arsenal remains bloated. True, it now deploys only about 1,600 strategic nuclear weapons — down from 12,000 in 1990 — and the Obama administration has proposed to cut the number to as few as 1,000 if Russia agrees.

“So what,” the authors ask, “is holding the United States back?” Their answer:

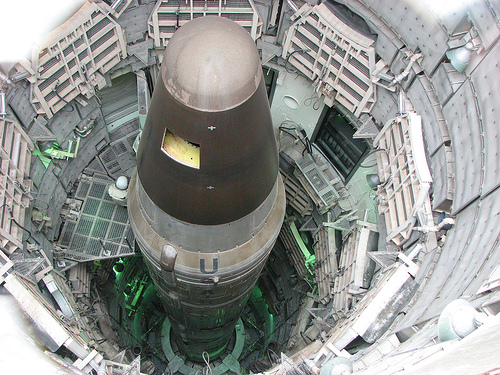

… Washington’s outdated nuclear strategy [that] is built on maintaining a triad of long-range delivery systems — bomber aircraft, intercontinental ballistic missiles and submarine-launched ballistic missiles — developed early in the Cold War.

Ostensibly the triad’s “main justification continues to be ‘survivability,’” write Friedman and Prebel. “But as is often the case in politics, the public justification differs from reality. … America’s nuclear weapons themselves are made to sidestep” Mutual Assured Destruction. In fact, “warhead design and ever-improving accuracy optimize the ability to destroy enemy nuclear forces before they launch, not retaliate afterward. Contrary to much official rhetoric, Washington’s nuclear war plans have always focused on a pre-emptive strike.”

The problem with relying on a first strike, they explain, is that it “encourages an arms race. Fear of a first strike encourages enemies to build more weapons for defense, requiring more weapons to pre-empt them, and so on. That helps explain why U.S. military budgets have long been insufficient to achieve clean first strikes against all rivals.” Actually, I’d never heard cost, as opposed to strategy and treaties, cited as a reason that the United States doesn’t possess an overwhelming first-strike nuclear-weapons force. After all, one of the reasons nuclear-weapons advocates use is that they buy a lot of defense cheap compared to conventional forces. Wait a minute ― since when doesn’t the United States possess an overwhelming first-strike nuclear-weapons force?

In any event, Friedman and Preble add their two cents to the argument against a nuclear triad. “These days, a submarine-based monad” ― one delivery system for nuclear weapons instead of three ― “makes more sense. … America’s current adversaries are unable to track its submarines, let alone target them. … Submarine-launched missiles are actually more accurate than the land-based kind.”

But remember, deterrence is a concept that preceded the development of nuclear weapons. In fact, according to Friedman and Preble, it’s (emphasis added) “easier to achieve than nuclear weapons enthusiasts typically admit. Even the Soviet Union, we now know, was eager to avoid a major conventional war, let alone a nuclear escalation. Today’s rivals are even more easily [than the Soviet Union] contained by American and allied conventional strength.”

Along those same lines, Tom Nichols writes in a National Interest titled The Case for Conventional Deterrence:

Today, only China and Russia can cause … grievous damage to the United States. … But what about small states, the “little guys” with the big weapons? These are nations – like North Korea, and soon, others – who will never be able to destroy the United States, but who could cause immense damage to an American or an allied city. Does the old bargain of a “nuclear eye for a nuclear eye” still hold? And should it?

Not sure how “immense” damage is worse than “grievous,” but we’ll let Mr. Nichols continue.

It’s time to be honest with ourselves. We are not going to inflict nuclear destruction on small states in crowded neighborhoods, killing thousands, maybe millions, of innocent people, and poisoning swaths of territory inhabited by friends and enemies alike.

Nichols points out how justified retaliation on our part barbaric overkill to the rest of the world.

Another reason we cannot credibly threaten to use nuclear arms against small states is that our retaliation would seem disproportionate, even to our own allies. … If the United States uses a nuclear weapon, whatever started the war will quickly become irrelevant, as attention will immediately turn to the casualties from the U.S. retaliation. … That footage, and not the initial attack on the United States, will be the images that will run in perpetuity on the world’s television screens, and perhaps might even achieve the propaganda victory the enemy wished for in the first place.

In other words, sympathy for the United States would be flipped even more dramatically than when we responded to 9/11 by laying siege to Iraq. “So what,” asks Nichols, “is to be done?”

The United States and its allies need to create a new and radically different deterrent against small nuclear powers, one that does not include threats of nuclear retaliation.

Referring to the leaders of such states, Nichols writes, “Nuclear threats sound hollow to such men, and they are.”

Threatening them with nuclear arms is difficult not only because such threats require them to believe that Americans share their stomach for mass murder, but because these regimes, in effect, hold all their neighbors hostage to the effects of a U.S. attack.

Nichols isn’t calling for, in lieu of deterrence or a retaliatory strategy, a pre-emptive strike as are nuclear hawks such as Charles Krauthammer. He advocates, instead, hitting a small state pondering a nuclear-weapons attack where it hurts most.

The key to deterring rogue states is to remember that their leadership cares [primarily] about their own survival and their control over their territory. … a vow that says “no matter how this ends, you will be dead and your regime gone” is one that enemy leaders can grasp because they’ve seen it happen in front of their own eyes.

“Real threats require real solutions,” Nichols writes. If “they use a nuclear weapon, they will precipitate a war with the most powerful alliance in the history of mankind, one that will end with their own deaths from a soldier’s bullet, a [conventional] bomb from the sky, or perhaps even at the end of a hangman’s noose raised by their own people.”

Okay, his “real solution” is somewhat, er, peremptory. Also, he writes that “rogue leaders considering the development or use of nuclear arms against the United States need to be spoken to in the only terms they understand.” Tossing about phrases like “rogue” is a recipe for making the leader in question dig in his or her heels. Furthermore, speaking to such leaders “in the only terms they understand” is condescending at best, racist at worst.

Still, the use of conventional arms and, especially, shooting an arrow into the heart of the leadership, is certainly preferable to overwhelming nuclear retaliation. Of course, such a drastic measure shouldn’t be undertaken until all attempts to treat the opponent respectfully in negotiations are exhausted.