On day 20 of testimony in the genocide trial against former Guatemalan dictator Efraín Ríos Montt last Thursday, Ríos Montt’s defense team, after a fierce exchange with the judge, walked out of the courtroom, proclaiming it will not be party to an illegal trial.

On day 20 of testimony in the genocide trial against former Guatemalan dictator Efraín Ríos Montt last Thursday, Ríos Montt’s defense team, after a fierce exchange with the judge, walked out of the courtroom, proclaiming it will not be party to an illegal trial.

Hours later, in a separate hearing, a separate judge—Judge Patricia Flores, who in January 2011 issued the genocide indictment against Ríos Montt—declared the trail annulled and said that the judge hearing the case, Judge Yazmin Barrios, “doesn’t know the law” and had no right to hear the case to begin with. That evening Guatemala’s attorney general, Claudia Paz y Paz, issued a press release, calling Judge Flores’ action illegal and vowing to use every means to resume prosecuting the case.

On Friday the tribunal reconvened, with the parties on their respective sides minus lawyers for the defense, whereupon Judge Barrios announced, “We will not allow the infringement of this tribunal’s independence. We are not required to obey an order that violates this court’s jurisdiction. We obey the Constitution, and a ruling by the Constitutional Court is the only one that can annul a trial.” She then said the trial is halted pending a Constitutional Court resolution.

The contention concerned procedure on an evidence ruling. Before the trial’s start, some defense evidence had been ruled inadmissible by a preliminary judge because it was submitted in violation of evidence requirements. On defense appeal, that ruling was overturned by the Constitutional Court on April 3, with orders to not expunge evidence already heard or stop the trial. Rather than delaying the proceedings and awaiting the Constitutional Court ruling, Judge Barrios had already provisionally allowed the evidence prior to the higher court’s ruling. Judge Flores on Thursday called this act illegal, and ruled the trial annulled.

Raised Skepticism

Earlier in the week, on April 16, 12 ex-government officials, including former Guatemalan vice presidents and civil war peace negotiators, published a full-page paid advertisement in Guatemalan newspapers condemning the trial and warning that a genocide conviction would bring serious dangers for the country and widen social and political polarization—raising suspicions about the origin of last Thursday’s events.

Marcie Mersky, Program Office Director at the International Center for Transitional Justice, said Judge Flores’ action was the result of “very strong pressure from [Guatemala’s] elites who defend in general the Army’s action during the country’s internal conflict” and who are “unwilling to be subjected to a judge, unaccustomed to being under authority by any institution.” Kate Doyle, Senior Analyst for the National Security Archive, reporting on the trial from Guatemala, called it “legal maneuvering.” Naomi Roht-Arriaza, a human rights law professor and an observer at the Ríos Montt proceedings, said the defense “knew the trial would be stopped days before it happened.”

Judge Flores’ annulment order triggered complaints by plaintiff groups, among them the Center for Human Rights Legal Action (CALDH), a civil party in the case, which filed challenges to the judge’s action with the Constitutional Court.

Under Guatemalan law, its Constitutional Court, which has been recently characterized by experts as “inconsistent” and “politicized,” has 10 days to resolve the annulment dispute. “Once these things get stopped,” warned Roht-Arriaza, “they are very difficult to get going again because there are a thousand ways for the defense to divert the matter and tie this thing up in knots.”

But the court hardly needed the 10 days. On Tuesday, April 23, the Constitutional Court announced decisions on six of the 12 legal challenges filed by parties in the Ríos Montt trial. Most significant among the resolutions, the Court rejected CALDH’s challenge to Judge Flores’ annulment, saying that the challenge was filed improperly. Second, the Court ruled that Judge Barrios must transfer the case file to Judge Flores within two hours in order for Judge Barrios, as the “legally competent authority,” to formally rule on the defense evidence admissibility issue resolved by the Constitutional Court in April 3. Third, the Court rejected a defense motion to expand its April 3 ruling to include the annulment of all trial proceedings and return the case back to its February 4 status, when Judge Galvez’ made his defense evidence ruling.

Reached for comment in Guatemala, Francisco Dall’Anese Ruiz, head of the UN-backed International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), declined to comment on news of the Constitutional Court’s resolution, or on what action his agency might take, until he could examine the decision and evaluate “whether it is legally acceptable or not.” Last Thursday, he issued a statement, which read in part, “If the crime was committed or not committed, if the accused is guilty or not, these are the exclusive decisions of the court that hears the case. Judges must remain free from any threat, because judicial independence is a human right.” Ruiz went on to say that CICIG is concerned about “paid ads, supplements and media statements, whose sole purpose is to influence the judicial decision to achieve an acquittal.”

Efraín Ríos Montt and José Mauricio Rodríguez Sánchez, his top intelligence officer at the time, were on trial in Guatemala on charges of genocide and crimes against humanity for the 1982-83 killing of 1,771 Ixil Mayans during the country’s 1960-96 civil war, marking the first time in history that a former head of state has been tried for genocide by his own country.

Standing President Implicated

Trial testimony over the past four weeks had detailed a pattern of deliberate killing. Some 100 prosecution eyewitnesses recounted family members who were shot at close range, hacked to death with machetes, bludgeoned with rocks and knives, strangled to death, burned alive, raped, and played with like toys and animals. Witnesses described the burning of houses and villages, and the destruction of crops and animals in an effort, they said, to wipe out all forms of life in Ixil villages. “They ended our culture,” said one witness about the military’s so-called scorched earth campaign.

Prosecution expert witnesses who have studied Guatemala’s civil war testified that civilians died in a defenseless state, that the Army’s kill-rate during the time in question was consistent with execution-style killing, and that the number of indigenous killed was eight times higher than that of non-indigenous.

As of last Friday, the defense, which had repeatedly protested the trial’s validity and complained about Judge Barrios, had yet to present 10 of the 12 witnesses it said it would present. “There’s been a lot of pressure from the defense, saying that the trial isn’t fair,” Roht-Arriaza said in an April 16 video statement from Guatemala. “The sense that I’ve got is that the trial is basically fair, the problem is that the defense isn’t doing a very good job defending, and I think that part of that is because they never thought this was going to come to trial, and so they really didn’t prepare very well.”

In a bit of prescience, she continued, “Really, [the defense’s] strategy is about delay. Their strategy is about either trying to get the Constitutional Court or the political process to halt this thing, rather than to carry out a defense.”

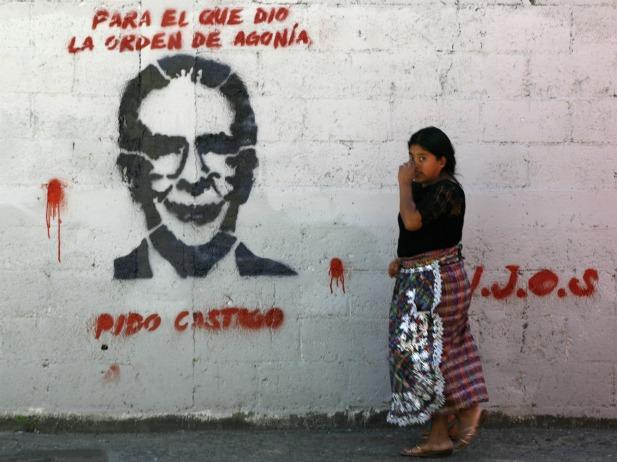

Political antagonism toward the trial seemed to ramp up after day 10 of proceedings, when eyewitness testimony placed Guatemala’s current president, Otto Pérez Molina, at the scene of massacres in the Ixil region in 1982. Pérez Molina was a Major during the Army’s 1982-83 counterinsurgency occupation in the region and has repeatedly rejected the notions that genocide took place, that massacres occurred, or that he was responsible for the killing.

But a former Army specialist testified on April 5 that Pérez Molina, his then-superior, commanded the Army’s rounding up of villagers for transport to military outposts, where they were then executed. “The soldiers, on orders from Major ‘Tito Arias,’ better known as Otto Pérez Molina,” Hugo Ramiro Leonardo Reyes told the court, “coordinated the burning and looting, in order to later execute people.” He said that villagers brought to military installations to be killed had come “beaten, tortured, their tongues cut out, their fingernails pulled out.” Reyes also named other Army officials in command at other Ixil region military installations where tortures and executions occurred. “As far as I could tell, the order was ‘Indian seen, Indian dead,’” Reyes said. He gave his testimony via videoconference from an undisclosed location under a witness protection program provided by prosecutors.

A spokesman for the president dismissed the Reyes allegation and said the testimony was politically motivated. “I recognize that there is freedom of expression, but President Pérez never participated in these acts. It has never been documented,” Francisco Cuevas said, adding that the president would not comment on the issue.

But the president did comment. On the day after Reyes’ testimony, Pérez Molina, to a mixed reception, traveled to Guatemala’s Ixil region and, dressed in Ixil clothing, distributed bags of food to peasants. “It is my joy and pleasure that the president visits us. He has done a lot for us,” said one. “He is one who kills and then goes to the funeral,” said another.

“I have nothing to hide,” Pérez Molina told reporters. “I did not participate in a single situation where someone died that was my responsibility. I’m not going to deny that I was in [the Ixil region at that time]. It’s true. But I was there to rescue the civilians, combat the armed guerillas and help the civilians.”

Ríos Montt had made similar claims before he was indicted for genocide in January 2012, declaring that his “intention was only to restore order and cooperation among the Mayan-Ixil.”

President Pérez Molina, who took office on January 14, 2012, was lauded for his initial support of the trial process. But on March 13 he stated publicly, “In Guatemala, there was no genocide,” and he repeated that statement on the trial’s start date. On April 17, Pérez Molina told reporters he not only supported the April 16 statement published by ex-leaders condemning the trial, but that he joined it. Last June his administration announced the termination of the country’s Peace Archives, an agency founded in 2008 to digitize documents related to Guatemala’s armed conflict, and earlier this year his government announced it would no longer recognize rulings by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights on crimes that occurred before 1987.

Pérez Molina is shielded from prosecution by Guatemalan law that exempts presidents and members of Parliament from criminal responsibility.

Guatemala’s 36-year civil war was the result of a seething anti-government solidarity among the country’s marginalized poor in the 1950s, which produced reform factions and eventually an armed insurrection. The government’s response, guided by U.S. counterinsurgency training, was swift and harsh. The repression’s bloodiest period came in the 14 months that Ríos Montt held power. Though he was one of 12 Guatemalan leaders who presided over the country’s “whirlwind of death,” Ríos Montt brought a precision and discipline to group slaying. In the end, 250,000 Guatemalan citizens were slaughtered or disappeared in the conflict.

Past efforts to prosecute Ríos Montt, now 86, for human rights violations had been hindered by a slow and malleable court system, by government agencies still loyal to the former dictator, and by his former status as a Guatemalan lawmaker and the same exemption law that protects Pérez Molina.

In 2012, after his parliament term expired and he failed to win reelection, Ríos Montt was charged with genocide and crimes against humanity in the Army’s “scorched earth” massacres against Ixil Maya in Guatemala’s El Quiché region. Four months later, in May 2012, Ríos Montt was indicted on a second and separate charge of genocide and crimes against humanity when a judge found sufficient evidence that Ríos Montt “knew of, controlled, coordinated and supervised the Army’s plans” during the 1982 3-day massacre of Dos Erres Mayans.

In January, after a year of delays brought by defense motions and appeals, a judge reactivated the Ixil case, rejecting defense protests that Ríos Montt is amnestied through the country’s National Reconciliation Act.