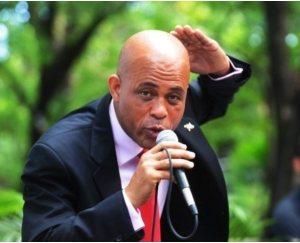

Michael Martelly

In this atmosphere of disillusionment, Michel Martelly, Haiti’s current president, entered office in May. A beloved musician often known for his lewd behavior on stage suddenly became the new face of Haitian politics. Tired of the status quo, Haitians saw Martelly as the change they needed from the corruption that has defined their politics for decades. His brash and no-nonsense attitude won the hearts and votes of Haitians from across society: rich, poor, young, and old.

However, his lack of credentials was glaring, and many doubted his ability to manage Haiti’s future. How could a man with absolutely no experience deliver on his promise to provide free access to education and healthcare for all? Despite the many doubts, Martelly won the presidency with approximately 22 percent of the meager 32 percent of Haitians that even bothered to participate in the election.

Lessons from the Past

Haiti’s past presidents have often been elected on the same premises. When former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide came to power in 1991, it was on the heels of the tyrannical Duvalier regime. People were desperate for reform, accountable government, and an end to miserable living conditions.

Aristide, a master of liberation theology, reached out to Haiti’s most marginalized populations, promising them free education, healthcare, literacy programs, and business reforms that empowered the poor. One of Aristide’s campaign slogans that rang resoundingly with the poor was “Lapé nan Vant Lapé nan Tét,” meaning “If there is peace in the stomach, there is peace of mind.”

During his first term Aristide made tangible reforms. He tried to raise the minimum wage for Haitian factory workers and launched a fierce literacy campaign. But Aristide’s polarizing nature led to his downfall. As he failed to deliver on his promises the Haitian people grew angry and agitated. Aristide was removed from the presidency twice, both via international intervention.

Déjà vu?

Like Aristide, Martelly began his presidency with the wind at his back, eager to make sweeping changes. But only eight weeks after his inauguration, Martelly’s honeymoon period has ended. He has yet to successfully pick a prime minister: parliament shot down Gerard Rouzier’s appointment, and the prognosis for Bernard Gousse’s nomination doesn’t appear any better.

Martelly also made big campaign promises including free access to education and universal healthcare. But these are goals that even the most developed countries in the world, let alone battered Haiti, have been unable to achieve fully. If Martelly is unable to deliver on his promises, he may very well be subject to the same fate that has plagued past Haitian presidents.

In order for Martelly to be successful, he must have the full cooperation of his parliament. Its decisions to reject his choices for prime minister seem based on politics instead of logic. It is time to break the shackles of corruption that has plagued Haitian politics for more than a century. Martelly can achieve nothing without the support of his government.

Martelly holds the hopes and expectations of the Haitian people in his hands, along with the skepticisms and judgments of his critics. Haiti’s brutal recent history suggests it is due an injection of good karma. Time will tell if Martelly’s reign will indeed be that, or yet another broken promise to the Haitian people.