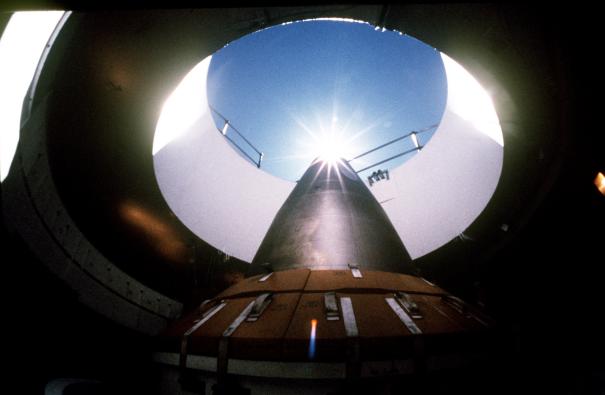

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Like a mirage, whenever it seems within reach nuclear disarmament recedes further into the distance. But, at least nuclear hawks no longer feel comfortable speaking on the record about nuclear “warfighting.” In fact, to keep the money flowing into the industry, they base one illusion – that nuclear weapons make us safer – on another: acting as if not only won’t they be used offensively, but defensively. In other words, the only function of “our nuclear deterrent” (as they invariably refer to the U.S. nuclear-weapons program) is to stand around and look threatening.

But it was only a few decades ago that commentators spoke more frankly of using them. Even though it was on the heels of the Nuclear Freeze movement, in the autumn 1987 issue of the Midwest Quarterly, Washington attorney James P. Scanlan addressed a national security concern slash ethical dilemma in an article titled Facing the Paradox of Deterrence (which I stumbled across while browsing JStor).

We must intend to retaliate in order to deter the Soviet Union from attacking us with nuclear weapons; but after the Soviet Union has unleashed a massive nuclear attack, there will no longer be any purpose in retaliating, at least no purpose sufficient to justify the substantial retaliation we must threaten in order to deter.

But, Scanlan wonders, is it really “so clear that we would have no purpose in retaliating after a massive Soviet strike?”

Naturally, if a nuclear power designated as the enemy, such as the then-Soviets, suspects that, for humanitarian reasons – or just due to an overwhelming sense of futility – the United States might fail to respond to an attack that disables it, the Soviet Union is motivated to stage a massive first strike. To thwart that, Scanlan writes (emphasis added):

…we must, through a system of automatic retaliation, deny ourselves the option of declining to retaliate.

As a prelude to building his case pro, he shoots down the usual reasons con. Winning, for instance.

[In] a tragedy in which 100 million Americans die, is an outcome in which 125 million Russians die conceivably preferable to one in which no Russians die?

How about, in his words, influencing the political future of the world?

It might be argued that an important purpose would be served by retaliation if it merely prevented the Soviet Union from dominating the world, as presumably it easily could after destroying the United States. But, regardless of how oppressive we may deem the existing Soviet regime, we must recognize that the geopolitical consequences of destroying the Soviet Union are utterly unpredictable; so too are the environmental consequences of the weapons it would take to do it, even upon those nations on whose behalf we would do so.

There’s always legitimization of the principle of deterrence, right?

As a rule there is a sound reason to follow through with threatened punishment even after the action that the threatened punishment seeks to deter has already taken place. It is to deter similar future conduct. … But, in the world that remained after a massive Soviet attack, it is unlikely that a situation of deterrence comparable to that existing now would exist again even in the relatively distant future. The possibility that retaliation would tend to stabilize such a situation is thus much too uncertain an end to justify the destruction that retaliation would entail.

Finally, what about good old revenge?

… whatever sense retribution may make in the realm of criminal justice, it clearly could never morally justify the killing of millions of people for the precipitate acts of a few of their leaders.

Scanlan then presents his case.

If it is true that a massive attack would place us in a situation where we could find no satisfactory reason to retaliate, such a course must be a plausible one to the Soviets.

Yes, I had to read that a few times as well. He apparently just means that the Soviets might attack if they sense a reluctance on our part to uphold our part of the bargain from hell — an eye for an eye.

… our vulnerability … remains a cause, not for concern, but for terror.

The only way to correct that vulnerability is to take whatever measures are necessary to deny ourselves the option of failing to carry out the threatened retaliation that is the foundation of our security.

He then considers how retaliation might be implemented.

The heart of Great Russia is Moscow, a metropolitan area of twelve or so million. … Four hundred miles northwest lies Leningrad, a city of almost six million that no longer holds the importance it had under the tsars, but that retains considerable historical and political significance. The irrevocable commitment to the complete destruction of these two cities alone would provide a considerable deterrent to a Soviet first strike. … by directing our threat at those parts of the Soviet Union that Great Russia deems most precious, we can achieve a satisfactory level of deterrence while minimizing the harm that carrying out that threat would entail.

Way to minimize the harm, Mr. Scanlan! By way of consolation, he concludes:

So if what I propose here is absurd, it at least is, to use Joyce’s words, a logical and coherent absurdity and, hence, immeasurably superior to the illogical and incoherent absurdity in which we are presently embroiled.

If automatic retaliation sounds familiar to you, it was one of the subjects of David Hoffman’s acclaimed book The Dead Hand (Anchor, 2010). The title refers to a sort of doomsday device programmed by the Soviets to fire nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles at the United States if sensors determined that the Kremlin had been destroyed in a nuclear attack. In fact, the system may still be in force.

Bearing in mind that half of deterrence is making sure that everyone knows you have a weapon, why, the question has been asked, did the Russians try to keep it secret? Even Dr. Strangelove wondered why the Russians failed to maximize the effectiveness of the cinematic doomsday device as deterrent by not publicizing it. Guess the Soviets thought there was never any doubt that they’d retaliate even if wiped out.

Sadly, even in this day and age, we’d likely do the same.