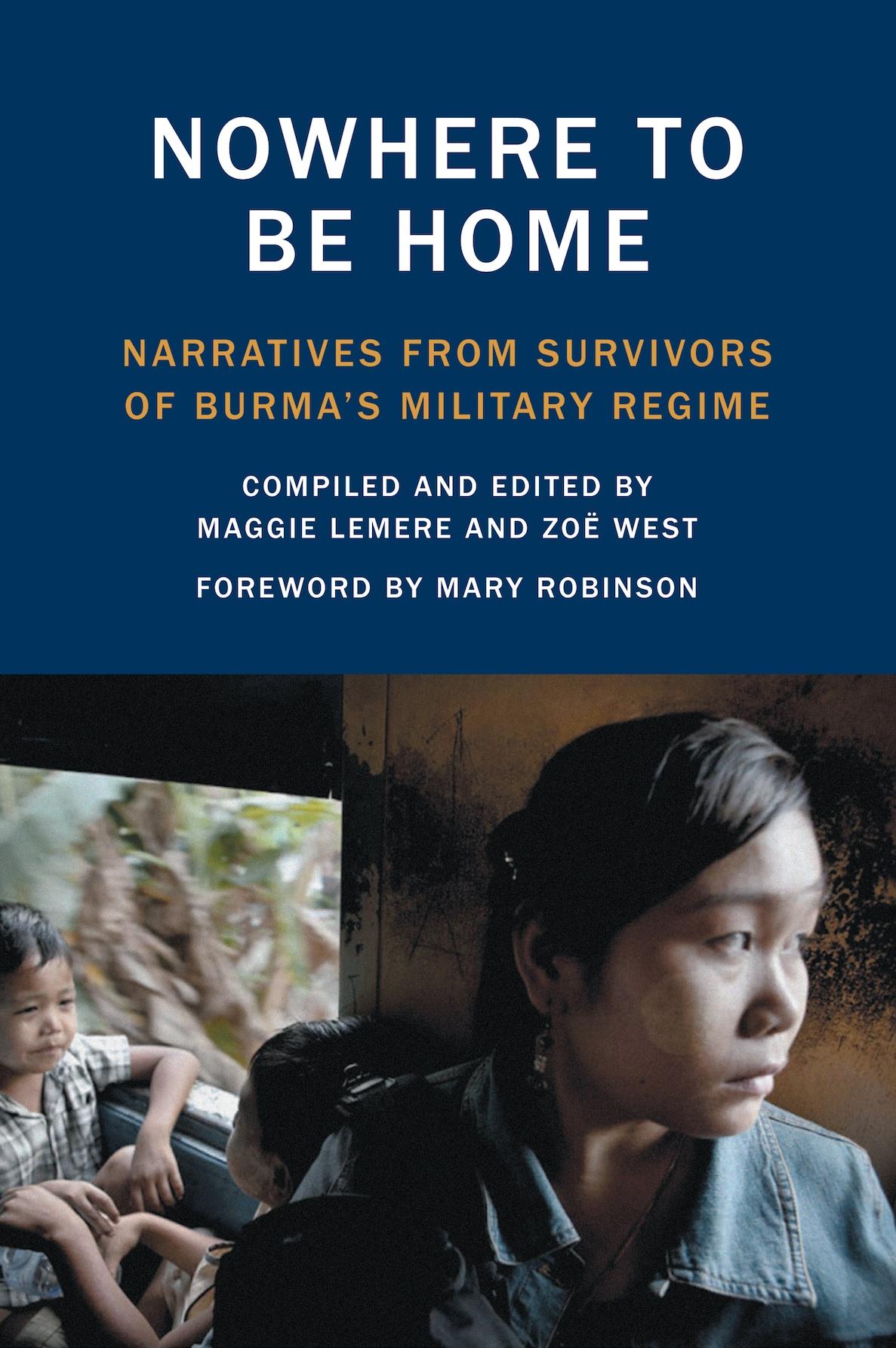

This month, McSweeney’s Voice of Witness releases Nowhere to be Home: Narratives from Survivors of Burma’s Military Regime, edited by Maggie Lemere and Zoë West. Nowhere to be Home is a collection of oral histories exposing the realities of life under military rule. In their own words, men and women from Burma describe their lives in the country that Human Rights Watch has called “the textbook example of a police state.” The book is the seventh title in the Voice of Witness series and is now available in the United States.

This month, McSweeney’s Voice of Witness releases Nowhere to be Home: Narratives from Survivors of Burma’s Military Regime, edited by Maggie Lemere and Zoë West. Nowhere to be Home is a collection of oral histories exposing the realities of life under military rule. In their own words, men and women from Burma describe their lives in the country that Human Rights Watch has called “the textbook example of a police state.” The book is the seventh title in the Voice of Witness series and is now available in the United States.

The following are excerpts from three of the oral histories in the collection.

Saw Moe

Saw Moe met us for interviews in the evenings, after closing up his bookshop in Thailand. He methodically described his time in Burma’s army, giving matter-of-fact descriptions of battle after battle, and eventually the event that forced him into exile. Saw Moe works part-time as a trainer for the Karen National Liberation Army, one of the armed opposition groups he spent much of his career fighting.

My parents are Karen, but I cannot speak the language because I grew up in a community of mostly Burman people in Rangoon, which is far away from Karen State. When I enrolled in school I had to say I was Burman— if I said I was Karen, people would discriminate against me. There were around sixty students in my class, and more than fifty of those students were Burman, so there were very few ethnic students. I couldn’t use “Saw” at the beginning of my name because that is what Karen people use, so I used a Burman name instead. But the students knew I was Karen anyway, so I was called “rodent Karen” and “smelly Karen.” That’s what they called all the Karen students.

When I joined the military, I still could not say I was Karen because I felt like I would not be promoted if they knew I was Karen. The Burmese military is dominated by the Burman ethnic group, and other ethnicities usually cannot advance in the military.

I joined the military voluntarily when I was seventeen. I joined because I liked fighting. As a young man, I wanted to be in battle, going from place to place. I planned to be a brigadier general or a colonel. It was 1979 or ’80 when I joined. My family didn’t like that I was in the army because they were afraid I would die in battle.

When I joined the army, the training course was six months long. In our course, there were about two hundred and fifty trainees. We had to train to have strong bodies first, so we could defend ourselves. For example, we had to run many miles each day. We had to learn how to shoot guns—we had to learn the “one enemy one bullet” system. When we practiced shooting targets, we had to search on the ground for every bullet that had missed the target. If you were missing even one bullet, you were not allowed to have lunch. If we made mistakes, the trainers beat us. We had to learn to follow all commands in order to avoid the beatings.

As soldiers, we were automatically members of the Burma Socialist Programme Party—the party of the former military regime—so we had to learn about party policies. During that time, the enemies we had to fight were the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), the Shan State Army (SSA), the Communist Party of Burma (CPB)’s army, and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). The CPB was our main enemy.

We had to learn about our enemies’ backgrounds and histories, how they started, what their aims were, and what type of fighting force they were—their artillery, their mines, and defense strategies. We were also trained in psychological warfare—propaganda. We had regular training until six o’clock, and then we had the psychological warfare training. There were two main things that they trained us to do: one was to believe in the propaganda, in the policies of the socialist party, and the other was to follow orders. You could not ask any questions, you could only listen. They trained us very well. The military trains soldiers how to do psychological warfare campaigns—how to persuade someone who dislikes you to like you, and how to make things unclear. For example, if we did bad things in a certain area, we would make the people believe that we didn’t do those things—that was part of the army’s strategy in areas where we were active. It was important for us to understand how to make other people or groups look bad too. We had a very rational way of lying to the people for our benefit. We would be very friendly with some people and show them a lot of things they could believe, while we had a hidden purpose.

We had to train and study very hard, but we had enough food and we were all learning together. All the trainees had the same spirit and we were all very happy, because we had chosen to join the army. Now it’s different—now the army has to force young people to join. Leading up to 1988, fewer and fewer soldiers were joining the army. Then after the ’88 uprising, we started forcing young people to join the Burmese army because they didn’t wish to join anymore—they hated the army.

Philip

We interviewed Philip on the front porch of his home in Loi Tai Leng, headquarters of the Shan State Army-South (SSA-S), as the rain pounded down on the roof and engulfed the verdant mountains surrounding us.1 Philip is a soldier and foreign relations officer in the SSA-S, one of the ethnic armies still in active opposition to the State Peace and Development Council. Philip spent eighteen years living as a monk, but was unsatisfied with his capacity to work for an independent Shan State. The fighting between the SPDC and the armed opposition groups creates dangerous and unstable conditions for villagers living in areas where there are conflicts with non-state armed groups. As part of the war against opposition groups in Burma, the SPDC uses the notorious four-cuts counterinsurgency strategy, which aims to weaken the opposition armies by cutting off their supplies of food, funding recruits, and information. They do this by forcibly relocating local populations, burning down houses and entire villages, detaining, torturing, and/or killing those suspected of having contact with opposition armies, and stealing or extorting food, crops, money, and livestock from villagers.2

According to estimates from the exile news organization Mizzima, there are twenty-four armed ethnic groups in Burma—nineteen have signed ceasefire agreements with the regime, while five remain in active opposition. Many of the ceasefires remain tenuous. Altogether, tens of thousands of armed opposition soldiers remain under arms.

The summer I was twelve, I came back to the village at five o’clock in the evening after taking care of my neighbor’s buffaloes and cows, and I saw fire and smoke. I heard shooting noises and people screaming; the village was overwhelmed with the smell and crackling sound of burning houses. I had no idea what to think. Whenever and wherever there was fighting between the Shan rebel soldiers and the Burmese soldiers, the villages would be burned. But usually when the Burmese government military burned villages, we had time to escape with a bag of clothes.

This time, the Burmese soldiers had burned down the whole village. Most of the people had gone into hiding for their safety. My family members were working on the farm, and when we went back to the village and saw that it had been burned, we ran into the jungle for safety just like the others. We had to keep moving from place to place through the jungle, until we reached a place were we could establish a new village.

My parents were really sad that we were not treated like human beings. This event had a big impact in my life—it made me care about human rights and want to fight for justice where there is injustice. Three different villages I lived in were burned down, and my family had to run all three times. Most of the time, we would run straight to the jungle and then move to another village. The Burmese soldiers wouldn’t tolerate a new village being set up in the same place.

I am a soldier in the Shan State Army because I want to work for my country, and because independence is the best way forward for the Shan people. English speakers call me Philip, but my Shan name is Yawd Muang. I don’t fight for myself, or for my family—I fight for my homeland. I have been a soldier in the Shan State Army for ten years. Before that, I was a monk for eighteen years.

When people talk about Burma, normally they only talk about two things: first, democracy and Aung San Suu Kyi; and second, about the drugs and the Golden Triangle.4 For international people to truly understand what the deep problems in Burma are, they have to come here and observe. In Shan State, everyone knows that Burmese soldiers go to the villages and commit human rights abuses. They take everything, rape girls and torture people. When the SPDC kills people, it’s like they’re killing mosquitoes. They don’t care, they just want to keep their power.

Mahatma Gandhi fought the British by protesting only with his hands—no weapons, nothing. He went into the streets and boycotted everything, with millions of people in India supporting the fight for independence, until the British left. But if you oppose the SPDC, you need to have a gun to protect yourself and protect your country. If not, they’ll kill you. If they catch a monk with a flower in his hand saying “Please forgive me, please don’t kill me!” they don’t care—they will kill you. They have even tried to kill people like Aung San Suu Kyi, because she’s very popular and the leader of democracy. They have guns; they have power.

Hla Min

Taken off the streets at nine years old and forced to become a child soldier, Hla Min was fighting on the front line in Karen State by age fourteen. He traveled for an entire day to meet us in Cox’s Bazar, a coastal city home to many Burmese refugees in Bangladesh—the country to which he fled in 2007 after the Saffron Revolution.

He told us his story until 1 a.m. that night, knowing it would be our only opportunity to meet before he returned to work on a tobacco farm the next day. Hla Min is one former child soldier in a country frequently cited for having the most child soldiers in the world.2 Analysts have pointed out that the Tatmadaw’s ongoing forced conscription of minors is one of the crucial factors allowing the military to increase its size and therefore its strength.

I’d like to tell you the story of how I joined the army as a child. I was nine years old, and I was living in the Hlaingthaya Township in Rangoon Division. It was a school holiday on the full moon day in November, and we were making a picnic. At around 8 p.m., one of my friends and I went out to buy some chicken. At that moment, an army truck came and took us. When they pulled us into the back of the truck, I found there were six or seven soldiers inside. My friend and I thought they were killers and I was worried. They made us lie down on the floor—there were no seats—and when I tried to shout, they covered my mouth with their hands. They said, “You keep quiet, you have to come with us.”

My friend and I were afraid but we didn’t say anything to each other. I had heard from my parents that soldiers beat and arrested people in my village. I’d also heard that soldiers shot people in the street, so I was afraid that they might kill me. The drive felt very long and I had no chance to run away. When the truck stopped, we got out and I saw the army base. My friend and I had been brought to a Burmese army battalion in Rangoon Division.

When we arrived at the army base, my friend and I were brought to separate cells. They were like prison cells, and they chained the doors shut.

My friend and I were very lonely while living at the army base. When we first arrived, we were not allowed to talk to each other. We were confined to separate rooms and we weren’t allowed to play together. After working all day, finishing dinner, and washing the dishes, we were locked up in the rooms again. Sometimes they scolded and beat me when I dropped a bucket of water, or a plate or bowl. During those times, I missed my home very much. I cried for my mother and for my family. I was the youngest of five, and I would play with my brothers and sisters and go to school with them. My parents really loved me and they always made me happy. Sometimes when I cried, I was beaten by the cooks and by the sergeants. Sometimes they slapped me and sometimes they beat me with a stick. While they were beating me they would say, “Why are you crying? Stop your crying!”

After about two months at the army base, I was sent to a recruitment center. I think it was called the Mingaladon Recruitment Center. When I first arrived, I found almost seventy children there who were around my age.

Sometimes the soldiers let me play with the other children, and sometimes they asked me to fight with other children. The leaders would come to us and tell us to wrestle, so we had to fight with each other until one of us fell down—the person left standing won. Sometimes I won, but sometimes I lost. I tried to beat the others and when I won, I was happy because I was given snacks. If someone won, they’d give a snack to them or buy them clothes. Sometimes the army soldiers and officers told me, “When you grow up, you will have to hold a gun like me.” When soldiers told us that, we felt really pleased.

I was around fourteen years old when I was ordered to go to the front line. My officer told me, “You have to go and fight the guerillas in Karen State.” During my training, and then at our battalion meetings, the leaders always preached about how cruel the rebels were, so at the time I believed the guerillas were trying to take my country and kill my people. We were asked to search for the guerillas and fight them.

One day, while I was carrying the unit’s cooking pot, I heard a blast behind me and I fell down, unconscious. When I woke up, I thought I had lost my legs, but it wasn’t a landmine, it was a remote-controlled bomb that had detonated. It had hit my backside and my head—the shrapnel had injured my right ear and cheek, my back, chest, and arms, but the pot had helped to protect me.

It took me about a month to recover. After I was better, I was sent back to my army battalion and then on to the front line again. While we were on the front line, our officers ordered us to completely destroy the local people. They told us that even the children had to be killed if we saw them. I saw soldiers abducting young girls, dragging them from their houses and raping them. At the time, I felt that those girls were like my sisters.

When I was in the army, I thought the guerillas were trying to break my country, to destroy my country—this is how I used to think. Not now, now I’m not the same. I don’t know why people join the military. As for myself, I was forced to be a soldier. If I had stayed with my family, I would not have been a soldier. I think the army takes children because they need to strengthen their forces, increase the number of soldiers. I think there is a reward for each soldier who catches a child. Any time a soldier recruits someone to join the force, they get a lot of money. Older soldiers told me that if they recruit someone, then they can quit the army.

Voice of Witness main website

To purchase Nowhere to be Home

A calendar of readings and speaking engagements for this book