This past October, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) suspended a three million dollar research prize funded by Teodoro Obiang, one of the world’s worst dictators. Shamed by an open protest letter signed by over 60 leading global activists, UNESCO was compelled to distance itself from a man who has long ruled Equatorial Guinea with an iron fist. Precisely how a leader cut from the same cloth as Idi Amin, Omar al-Bashir, or Nicolae Ceausescu came to finance a UN prize in the first place is a truth stranger than fiction.

This past October, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) suspended a three million dollar research prize funded by Teodoro Obiang, one of the world’s worst dictators. Shamed by an open protest letter signed by over 60 leading global activists, UNESCO was compelled to distance itself from a man who has long ruled Equatorial Guinea with an iron fist. Precisely how a leader cut from the same cloth as Idi Amin, Omar al-Bashir, or Nicolae Ceausescu came to finance a UN prize in the first place is a truth stranger than fiction.

For the past three decades, Obiang has proudly presided over one of Africa’s most devastating humanitarian and political disasters. With a per capita GDP comparable to Portugal or Korea, Equatorial Guinea’s national income is the highest in sub-Saharan Africa; and yet over 60% of the population struggle to live on less than a dollar a day. Since oil was discovered in 1995, President Teodoro Obiang’s family and close associates have grown fabulously wealthy, while the majority of Equatoguineans remain mired in poverty.

The kleptocracy in Africa’s only Spanish-speaking country is neither a secret nor a surprise. Although respected international advocacy organizations including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International regularly condemn the injustice and violence of Teodoro Obiang’s government, it took an outraged letter from Equatoguinean exiles, backed by international heavyweights including Mario Vargas Llosa, Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, John Polanyi, Desmond Tutu and Graça Machel, to persuade UNESCO that the Teodoro Obiang Nguema life science prize was “inimical to [its] mission” and “an affront to Africans everywhere who work for the betterment for our countries.” This is the strangeness of Equatorial Guinea’s plight. No matter how many dubiously-funded multimillion dollar houses Obiang’s son buys in Malibu, California, how many dissidents are tortured and killed in Malabo prisons, or how many human rights exposés are published in the world’s leading publications, when Teodoro Obiang travels to the United States, France, and the UN, he receives a red carpet reception—as long as he promises to do better.

Obiang’s Ace in the Hole

Part of this maddening paradox is the result of Equatorial Guinea’s massive oil reserves, which, according to one U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations report, have created an “increasing capacity to buy diplomatic influence.” The extent to which oil resources distort Equatorial Guinea’s global standing is evident in the most recent UNDP Human Development Index. More than any other country in the world, Equatorial Guinea’s abysmal figures in health, education, and other social indicators are masked by its oil-bloated national income. When national income is removed from the human development index calculations, Equatorial Guinea’s ranking plummets. Similarly, oil wealth critically lubricates the country’s bilateral relationships. Last year, a thorough Human Rights Watch report analyzed the schizophrenic U.S. government relationship with Equatorial Guinea in terms of the American oil addiction.

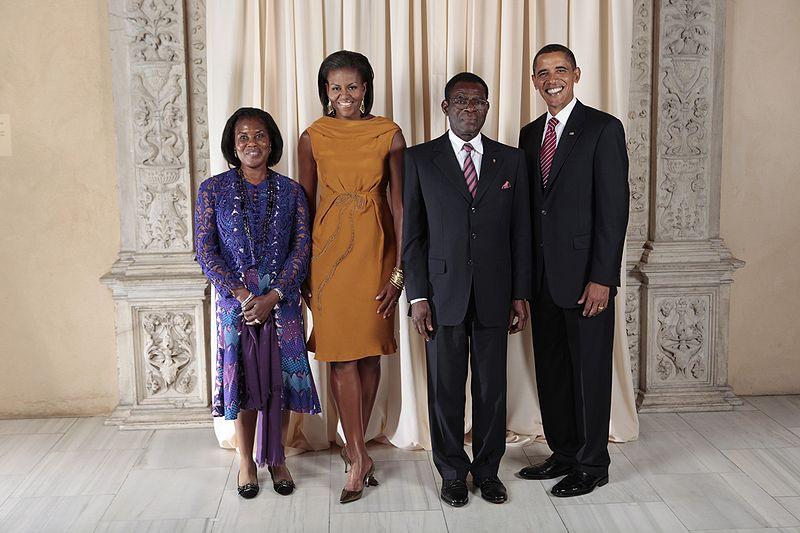

Alongside a number of excellent journalistic exposés, the U.S. State Department itself annually condemns Equatorial Guinea in the strongest language. The most recent report listed torture, killings, unfair labor practice, child trafficking, and other abuses among the country’s troubles. John R. Bennett (ambassador from 1991-1994) refuses to have his picture hung in the U.S. Embassy in Malabo, a building owned by a known torturer. Similarly, Frank Ruddy, ambassador during the Reagan administration, vocally criticizes his government’s continuing relationship with a man he describes as a thief, a tyrant, and a thug. Despite far-ranging and high-placed criticism, the thawing of the U.S. government’s relationship with the Obiang administration has steadily continued. Pressured by the U.S. oil industry, George W. Bush quietly renewed state ties with this noxious regime in 2000 and today, the United States is Equatorial Guinea’s single largest investor. Despite hopes to the contrary, President Obama’s administration has not altered the country’s course. A chilling 2009 photograph documents Barack and Michelle Obama smiling broadly with Teodoro Obiang and his wife; this picture is prominently displayed on the Equatorial Guinean government website.

A recent article in the New York Sun described the U.S. government’s continuing support for Equatorial Guinea as a source of growing tension between Barack Obama’s “human rights absolutists” and Clintonian “pragmatists” who think it wiser to “nudge [Obiang] toward reform” than to “wag an accusatory finger.” The Sun quotes lobbyist and former Clinton advisor Lanny J. Davis, a man currently on Teodoro Obiang’s payroll to the tune of $2.5 million, explaining that “it is in the interests of the U.S. as well as those who care about democracy and human rights to take up President Obiang on his request for help to implement his reform program.” This perspective ignores the lessons of Equatorial Guinea’s long political history. Depicting Teodoro Obiang as a credible reformer or oil companies as entities able to “nudge” a dictator toward human rights responsibility is at best naïve and at worst a highly strategic blindness to Equatorial Guinea’s troubled past.

The all-powerful pull of crude oil is not the whole story. Teodoro Obiang’s evasion of pariah status is also linked to his ability to deftly manipulate reform rhetoric (with the help of an army of highly-paid lobbyists in the United States and Europe) to circumvent the international community’s moral opprobrium. Meanwhile, the Equatoguinean people continue suffering under this repressive regime. In the most recent outrage, Obiang’s regime executed four men without a fair trial in August. A Malabo citizen named Robert, quoted in a 2009 Christian Science Monitor article, said it best. “The president is just lying to the international community so people will think that he is [improving] democracy and that he is [having legitimate] elections…It is a game so he can benefit.”

Gaming the System

Over the past 30 years, Obiang has perfected a formula of publicizing small rhetorical capitulations to good governance ideals while leaving the architecture of his state’s repression entirely unchanged. In 1979, after propelling himself into power by assassinating his uncle, Obiang publicly promised to restore the struggling country to democracy and received UN technical and financial assistance in return. Thirty years later, Equatorial Guinea’s long-awaited democracy remains elusive. During the 2008 legislative elections, the authorities arrested a leader of a banned opposition party. He was later found dead in his prison cell in a suspicious “suicide.” In the 2009 presidential elections, Teodoro Obiang prevailed with 95 percent of the vote in an election where soldiers manned all the voting stations, ballot boxes were not sealed, and independent election observers were prohibited.

The gap between Teodoro Obiang’s reformist rhetoric and the reality of entrenched injustice is even more striking in the administration’s maneuverings around Equatorial Guinea’s oil revenues. In 1997, Obiang inaugurated the country’s first National Economic Conference, where the president loudly proclaimed its intention to be transparent and rational in oil revenue. The conference recommended that the government create an independent agency, accountable to the parliament, to audit the state’s revenue streams and expose corruption and irregularities. More than a decade later, this agency does not exist. Again in 1999, the UNDP consulted with the government to draw up a plan for addressing transparency and institutional capacity-building. This plan also never made it off the paper.

In his 2010 Capetown Global Forum speech, Teodoro Obiang again pledged to standards of oil revenue transparency by touting his burgeoning relationship with the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), the global oil monitoring agency, as evidence of a five-point reform program. In reality, Obiang has been executing the same evasive dance with the EITI as with earlier accountability efforts. In 2007, Obiang applied for Equatorial Guinea to be recognized as an EITI Candidate, meaning that in two years, the country would be expected to progress toward basic standards of oil revenue transparency. When little progress had been made in the allotted time, the president applied for an extension. The EITI board refused the extension request and revoked Equatorial Guinea’s status as a candidate country, essentially throwing the country of the monitoring program. Just two months later, Teodoro Obiang was boasting in Capetown about his efforts to seek EITI candidacy, again. This type of disingenuousness is the hallmark of Teodoro Obiang’s rhetoric of reform; as one Global Witness campaigner dryly noted “transparency doesn’t take ten years.”

This dynamic has long been a part of Obiang’s politics. In 2002, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights decided to end its special monitoring of Equatorial Guinea because of allegedly improved conditions. However, the outgoing special representative vocally disagreed with the lessening of human rights scrutiny. In his resignation letter, Gustavo Gallon Giraldo boldly stated that “unfortunately, nothing has changed in Equatorial Guinea.” What had changed, he speculated, was the composition of the Commission, which “endorsed facts and statements that are at odds with reality.” Exploiting this gap between rhetoric and reality is at the core of Teodoro Obiang’s global public relations campaign. In the June 2010 speech at the Capetown Global Forum, Teodoro Obiang’s manipulation of reform rhetoric was on display as he urged the international community to “turn the page” on Equatorial Guinea.

Evading Responsibility

The president’s first step in avoiding responsibility is to acknowledge the country’s woeful situation, and then quickly attribute the problems to the colonial and early independence history. The fact that he himself has been at the helm for the past three decades, and has managed oil-engorged coffers for the past fifteen years, is irrelevant in his accountability assessment. “This is about developing a country that started from nowhere,” he gravely informs international investors. By invoking an exceptionally bleak history, Obiang cast his efforts, however meager and incomplete, as credible nation-building. After all, if “nothing” existed prior to his leadership and Equatorial Guinea was “nowhere,” any improvements, however small, are recast as positive gains rather than shameful underachievement.

Next, Equatorial Guinea’s president waxes eloquent about his tireless efforts to combat “mindsets rooted in underdevelopment” and “habits… such as corruption, illiteracy, tribalism, political opportunism and on and on.” This shameful circular reasoning describes the nation’s underdevelopment as a force rooted in the country’s people, rather than as an injustice done to them during the past three decades of state violence and neglect. Deriding a national “habit” of illiteracy is supremely cynical given that the wealthy Obiang administration’s public education expenditures are a quarter of the sub-Saharan average. By naturalizing underdevelopment, this oblique analysis deftly shifts responsibility again—this time to the country’s people.

Continuing on, Teodoro Obiang entreats the international community to “remember that Equatorial Guinea is a relatively young nation, inexperienced… we must take into account that we are a country only 42 years old,” the president reminds his audience. This framing could well be described as a hardship exemption based on claims of backwardness and inefficiency. If conditions are not improving quickly, says Teodoro Obiang, the world should just sympathize with the poor Africans muddling about at the “new” work of nation-building. After all, they can only do so much. By plying disheartening stereotypes of African underachievement, Obiang thwarts demands for basic human rights and real reform.

. Finally, Obiang proudly notes his generous response to Hurricane Katrina, the Tsunami, the famine in Niger, the Nigerian pipeline explosion, the volcano’s eruption in Cameroon’s Victoria Peak, and the explosion of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. But regardless of how much money he doles out to humanitarian causes—— or how earnestly he trumpets his desire to “partner with the world’s democracies,” Teodoro Obiang can never be counted as a good global citizen.

The longer the international community focuses on Obiang’s resources and rhetoric at the expense of a hard-nosed assessment of his policies, the bleaker the future for Equatorial Guinea. Academic experts like Alicia Campos Serrano have warned that Teodoro Obiang’s repressive policies, unchecked, will be the foundation for future instability and greater hardship for Equatoguineans. By developing a single-sector oil economy, Obiang’s administration has gutted the country’s agricultural sector in favor of lucrative oil production. But as the people of Nigeria, Angola, or Sudan can verify, you cannot eat oil. The country’s lagging agricultural sector and increased urban migration have created a host of new problems. Serrano describes the company towns that have risen up around the country’s oil industry, many of which keep more than 50 percent of oil workers’ salaries; she describes an “exponential” increase in the trafficking of women and children to these areas. Serrano also highlights the political cost of Obiang’s exploitation of the national economy and the huge personal profits he has garnered. A series of reported assassination and coup d’état attempts in Malabo suggest that scores of mercenaries and challengers wait in the wings for their turn to benefit. The president’s repression can contain this erupting violence for only so long.

By appropriating the language of human rights reform Teodoro Obiang has been able to whitewash Equatorial Guinea’s social devastation and political repression as post-colonial African development. As long as powerful members of the global community continue to avert their eyes to the gap between Obiang’s rhetoric and his policies, they will be unable to pressure either his government or subsequent leadership to prioritize the human rights, security, and development of the Equatoguinean people. By undermining the moral authority of international governance mechanisms, the free pass given to President Obiang paves the way for further abuse in Equatorial Guinea and anywhere else where dictators act with impunity.