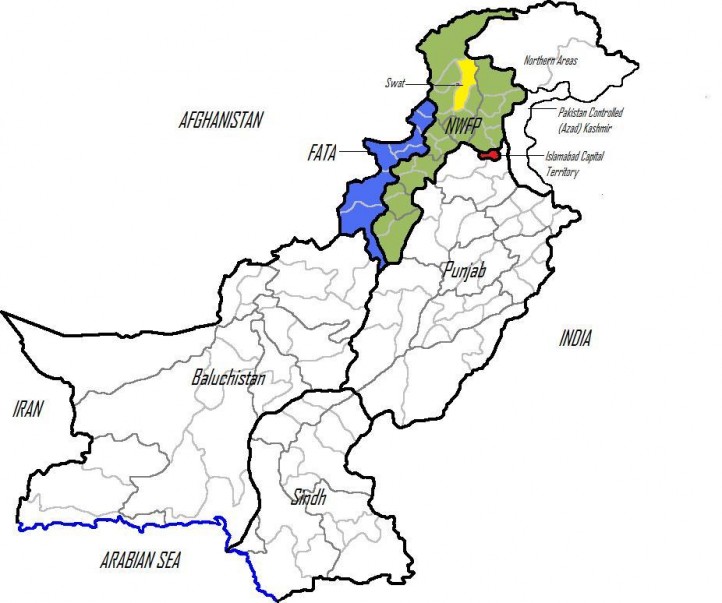

If the bucolic Swat valley, tucked into the Himalayas less than 100 miles from the capital city of Islamabad, is a bellwether for Pakistan’s war against the Pakistani Taliban, the war is going badly. The Swat District — an integrated part of Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province (NWFP) as opposed to the autonomous Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) — has been beyond government control since 2007. In this period the Tehreek-e-Nifaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi (Movement for the Enforcement of Mohammaden Islamic Law), a militant Pakistani Taliban group,2 thoroughly destroyed the threadbare state institutions that existed in the area. Most notably they targeted schools and the police force. Rebuilding these will take years.

The Pakistani government concluded a truce in Swat in February 2009. The embattled left-leaning provincial government in NWFP, whose parliamentarians the Islamist3 Taliban ruthlessly targeted, urged the central government to do so. It passed the Nizam-e-Adl (System of Courts) regulation that instituted Sharia courts under de facto Taliban control. The deal provided the Pakistani Taliban with an autonomous enclave where they freely dispensed frontier justice and, according to their spokesman, prepared to spread their version of Sharia to all of Pakistan.

The truce came after months of fighting between government and Taliban forces following previous failed deals that merely gave the insurgents room to regroup and neutralize community opposition through widespread terror. The conflict killed and maimed thousands, and displaced hundreds of thousands more, an indication of the vicious zeal of the Taliban and the indiscriminate brutality of the military response. Despite the staggering human cost of the engagement, a military contingent of up to 16,000 troops failed to dislodge some 3,000 Taliban fighters. In this context, the ceasefire accord was a de facto ceding of territory but also an abdication of the state’s de jure legitimacy.

The ceasefire quickly unraveled when the Taliban used the military withdrawal to bleed into the surrounding areas, particularly Buner, Dir, and Malakand. Under intense U.S. pressure, the military has once again invaded Swat, with tanks, heavy artillery, and air support. It has urged residents of Swat and neighboring districts to flee, displacing up to 3 million people — more than half the total population. The United Nations warned that the Swat valley could be the worst refugee crisis since the Rwandan genocide of 1994.

Details of the latest offensive are sparse since the military has prevented independent observers and media from entering near the combat zone. But even if it declares victory in this fourth major military offensive in Swat since November 2007, the military is unlikely to eliminate the Taliban in Swat and hold territory long enough to begin much-needed reconstruction. Further, the relief effort is underprepared, underfunded, and overwhelmed. Ill-preparedness for the arduous tasks of conducting effective humanitarian and reconstruction operations could turn even a decisive military victory into apropaganda and recruiting coup for the Taliban.

Figure 1: Map of Pakistan highlighting the Swat region

Similar stories unfold from Waziristan to Bajaur in the Tribal Agencies: limited advances culminating in ceasefires signed from a position of weakness and in the absence of any broad-based dialogue with affected communities. Under the umbrella of these armistices, militants are projecting their power and spreading their influence deeper into Pakistan. The sophisticated attacks in recent months in Islamabad, Rawalpindi and Lahore — Pakistan’s political, military, and cultural capitals, respectively — demonstrate the reach of the Taliban network. It also marks the end of the phase where the insurgency could be contained in the miserable badlands on Pakistan’s periphery. The fight is now moving to the very heart of Pakistan in the province of the Punjab.

Figure 2: Map detail of the highlighted area in Figure 1.

Why has the seventh-largest military machine in the world —battle-hardened in wars, ongoing border disputes, numerous external and internal campaigns, and peacekeeping missions — been so ineffective against the Taliban militia?

A stock explanation from analysts and officials alike is that the Pakistani military, with conventional warfare against archenemy India as its raison d’être, possesses inadequate capability to wage a successful counterinsurgency campaign. Moreover, the army isn’t sufficiently motivated to battle its compatriots and coreligionists. Such reasoning is the basis for the Pakistani military’s successful bid to seek a renewed aid package from Washington. The new deal provides $3 billion a year to the military, contrasted with half that amount for development assistance.

This conventional wisdom, however, is inadequate and obscures a deeper and more worrisome issue. Pakistan is facing ideological blowback from over five decades of using political Islam as a tool of domestic and foreign policy.

A History of Counterinsurgency

The Pakistani army has been fighting indigenous insurgencies for as long as it has fought India. It fought its first internal uprising in 1948, less than six months after Pakistan emerged as a sovereign state following the dismantling of the British Empire in India. The reason for its deployment was the Khan of Kalat’s declaration of independence of what is now the province of Baluchistan. Pakistan’s military subdued and annexed the state, swiftly putting down a resulting rebellion supported by Afghanistan. 4

Baluch resentment has boiled over into armed insurrection a number of times since, notably in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, and then recently from 2005 to 2008. Each time the military moved with dispatch to quash the uprisings. At the zenith of operations in the 1970s, the government deployed more than 80,000 troops along with massive armored and air support. Most recently, the military refused all overtures of a negotiated settlement, including those made by a special parliamentary committee and its own government. Instead it vowed to crush the militants. “Don’t push us,” said the then-Army Chief and President General Pervez Musharraf, or “you won’t even know what hit you.” Underlining its seriousness, the military dropped a bomb on the venerable octogenarian politician and rebel leader Nawab Akbar Bugti, igniting a firestorm of protest across the province. The military and intelligence agencies “disappeared” thousands of Baluch political activists, taking advantage of the legal and moral blindspots of the Global War on Terror. The whereabouts of many of them remain unknown.

The war for independence in the former province of East Pakistan (now the independent Bangladesh) in 1971 is just as telling. The province declared independence after Pakistan’s then-military rulers refused to allow it to form a government after winning a majority in the elections of 1970. Pakistan faced over 100,000 armed Bengali rebels, led by trained military officers and troops that had hitherto been part of the Pakistani army. The insurgents enjoyed the benefits of sanctuary, supplies, and training provided by India. Yet the Pakistani army, along with tens of thousands of militant volunteers drawn from right-wing Islamist parties, was more or less set to extinguish the rebellion. Decisive Indian military intervention on the side of the Bengalis stymied Pakistan.5 The military command’s ruthlessness in East Pakistan led to serious accusations of war crimes that continue to haunt Pakistan to the present day.

In addition, the military has successfully faced down a number of low-grade insurgencies in rural Sindh, the city of Karachi, and indeed the provinces of NWFP and FATA in the 1980s and 1990s.6 The military also possesses extensive experience in organizing massive guerrilla campaigns in Afghanistan and Kashmir, giving it an inside knowledge of insurgency that only a few other militaries can equal.7>

In all the above cases the military fought compatriots and co-religionists largely employing tactics of asymmetric and guerrilla warfare. In each case its counterinsurgency techniques were disproportionate and undeniably brutal. Yet they were ultimately successful in quelling the uprisings without making any notable concessions to the insurgents (with the exception of East Pakistan, which turned into a conventional war with India).

But not anymore. Why is the current military operation against the Pakistani Taliban so different?

The army’s present counterinsurgency difficulties are not entirely explained by the military’s alliance with the United States or its ambivalent relationship with the Taliban. In any case the army’s position toward the Taliban has hardened over the last two years, as Taliban commanders have increasingly targeted state institutions and the military in particular. Nor are the present government’s disorganization and institutional inertia sufficient reasons. A guardian army that has ruled Pakistan for most of the country’s existence, firmly handles all national security issues, and has tens of thousands of personnel already deployed and under attack would not wait on a civilian government’s instructions. 8

The key difference is the present insurgency’s ideological dimension. Whereas all previous insurrections have been primarily secular ethno-nationalist, the Pakistani Taliban for the first time represent a serious Islamist challenge to the Islamic Republic.

A History of Islamization

Discussions of Pakistani politics and the present Islamist insurgency seldom stray far from familiar frameworks. Under commonly held perceptions of Pakistan’s history, the country’s Islamization begins only in the late 1970s with the sclerotic military dictatorship of General Zia ul-Haq. The United States declared Pakistan a “frontline state” in the battle for freedom against the Soviets and communists in Afghanistan and, with the help of its Western and Arab allies, sponsored the anti-Soviet jihad from Pakistani soil. They accentuated the Islamic dimension of the insurgency, 9 strengthening militant Islamist forces, madrassah networks, and jihadist internationalists. This led to a stupendous growth and radicalization of Islamist and right-wing factions in Pakistan. Drug smuggling and weapons pilfering by Afghan warlords and the Pakistani military — with U.S. collusion — resulted in the influx of the “heroin and Kalashnikov culture” and skyrocketing levels of violence.10 U.S. policy toward Pakistan in the aftermath of the Soviet and Western withdrawal from Afghanistan and the region can be summed up by the words “do as thou wilt.” With the Cold War at an end and the Gulf War on the horizon, Pakistan too was abandoned. Most aid and assistance dried up and it was left to its own devices. It had free reign in installing the ultra-orthodox Taliban regime in Kabul, in the process utilizing and entrenching all the criminal and Islamist strains that the anti-Soviet jihad had birthed.

This history contributes to explaining the relative strength of the Islamists in Pakistan today. But it doesn’t entirely account for the relative weakness of Pakistan’s million-strong army in its attempts at confronting an estimated 15,000 Taliban fighters. Pakistan’s current predicament lies in the fundamental ideological orientation and mobilization of the state.

Pakistan was created in 1947 as a homeland for India’s Muslims. A largely secular and landed elite led its nation-building struggle. These elite have continued to govern it to the present day, in collusion with the military that has ruled Pakistan for much of its life. Pakistan is an ethnically diverse country with adherence to a shared religion — that too fractured by multifarious sectarian differences — as the only common denominator. Thus, it has been plagued by an unresolved search for national identity. Is it to be a heterogeneous and pluralistic Muslim country or a doctrinal Islamic state?

This debate frames some of the basic political choices available to Pakistan. Its secularist, leftist, and ethnically based parties have long supported a loose federation of Pakistan’s provinces, resolving questions of identity in favor of regional ethnic and cultural ties. Its ruling elite, and particularly its colonial-style military and bureaucrats, have stood for a strongly centralized state that can assert control over provincial resources to build up its internal and external coercive capacity. 11 Strong regional identities would undercut such a centripetal state. Therefore, from its very earliest days, political Islam has been utilized as a means of mobilizing identity,12 of subsuming regional affiliations into the political agendas dictated by the center.

Encouraging a common Islamic underpinning to an otherwise ethnically and socially diverse country has been a means of stressing integration of the state’s peripheries with the core. It’s a strategy of bringing the badlands of Baluchistan, NWFP, and FATA under the comfortable hegemony of the Pakistani heartlands of the Indus Valley: the provinces of Punjab and, to a lesser extent, Sindh. This religion-based identity serves to combat centrifugal ethno-nationalist tendencies and reinforces control of the over-centralized colonial state. This state, and the bloated military that is its ultimate guarantor, has been supported by the United States and the West in general since the 1950s.13

The Pakistani state, with the military as its dominant institution, has used all means of political and social engineering to emphasize an Islamic ideology and orientation for the country. In fact, Pakistan is the first country in the world to adopt the appellation “Islamic Republic” as part of its official designation. It has used religious notions of jihad in its wars against India and its own ethnic minorities, crafted educational syllabi to teach a warped Islamicized history, controlled media to disseminate official propaganda, and passed laws to persecute non-Muslims and limit critical discussions of political Islam. The country’s ruling elite has also long sought to equate loyalty to Pakistan with fealty to Islam, labeling most serious expressions of dissent as un-Islamic.

Most importantly, the state, through the dominant institution of the military, has stifled democratic aspirations by controlling or manipulating the political arena outright. It has created and patronized several Islamic and right-wing political parties. 14 Pakistan’s constitution explicitly recognizes both its (albeit undefined) Islamic ideology as well as the imperative to bring all laws in line with Sharia. Islamic ideology as a result has become the keystone of Pakistani identity — not through an organic grassroots process but rather through the supra-political machinations of the authoritarian state. In the process, and quite by design, the state has discredited largely secular and progressive nationalist forces. For instance, the disparaging Urdu term ladiniyat, meaning “irreligious,” has entered the vernacular as the word for “secularism.” It is thus unsurprising that the space for expressing public dissent on the enforcement of Islamic laws and mores has dramatically contracted.

Such processes grew starker under the regime of General Zia ul-Haq, as both juridical and other forms of state and social coercion multiplied so as to disseminate the official, Islamic viewpoint and silence all opposing stances. But General Zia and his policies are not an anomaly within Pakistan’s political development. They are a natural outcropping of the government’s use of political Islam as state ideology. Zia simply read from the blueprints that had already been crafted by Pakistan’s previous (mostly military) rulers. That the fallout from his regime has been more toxic says less about his role as an arch-villain in Pakistani history than it does about the tipping point that was reached in the state’s Islamization project. Pakistan was already at the banks of the Rubicon; Zia merely swam across.

The majority of Pakistanis may disagree with the Taliban’s puritanical zeal. Indeed, Islamists traditionally fare poorly at the polls. 15 But the broader social trends incubated by the state itself have made it difficult to openly counter the Taliban’s key message of propagating Sharia law and public displays of piety and religiosity. The Pakistani establishment has for decades been cynical in its use of political Islam as a tool of domestic and foreign policy. It has lionized the struggles for a theocratic state embodied by the Taliban and other Islamic holy warriors in Afghanistan, Kashmir, and beyond. Thus, for many the Taliban’s proclamations of being “jihadis” or “mujahideen” garbs them in the cloak of popular Islamic legitimacy. Such a perception of legitimacy has been (and continues to be) fostered by the state itself.

Ideological Blowback

The Pakistani Taliban and their vocal sympathizers, largely radicalized and feted through the state’s ideological apparatus, are now turning their ideas — and their guns — on the state itself. They are proving increasingly adept at appropriating the official discourse of Islamic legitimacy and recasting it in a radical mold. The Taliban have been assisted immeasurably in this by the political and ideological alienation of the Pakistani state in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Previously, Pakistan brandished its Islamic credentials by presenting itself as a champion of regional causes from Afghanistan to Kashmir. Its foreign policy reorientation after 9/11, when it allied itself with the United States against its former Taliban allies and curbed its support for militant Islamists in Kashmir, has called its Islamic commitment into question. But Pakistan has failed to re-imagine its moral authority in different normative terms.

In effect, the Taliban are stepping into this breach. They are out to realize the state’s rhetoric. This subverted discourse is not precisely illegitimate or terroristic since it originates with the state. The state finds itself hamstrung in its ability to craft a strategic narrative on taking concerted action against the Taliban, in military as well as political terms. From a strategic perspective, this is the primary reason Pakistan’s vast military machine is foundering against the Taliban. Opposing the Taliban’s message of Islamization would hurt the legitimacy that the state has tried so hard to embed within Islamic qualifications. However, acknowledging alternative actors for such Islamization subverts the state’s de jure authority. In either case, the state stands to hemorrhage its legitimacy.

This schizophrenia is reflected in the ambivalence and prevarications of the broader public as well as the elected parliament on the issue of Talibanization. Recent opinion polls indicate that as many as 69% of Pakistanis recognize the Taliban as presenting a profound threat to Pakistan. Yet 56% also state that they support the Taliban’s key demand of spreading Sharia to all parts of Pakistan. Similarly, nearly all parties in the Pakistani parliament, from the rightist Jamaat-e-Islaami to the secular and left-leaning Awami National Party or the ruling Pakistani Peoples Party, voted in favor of the Nizam-e-Adl Regulation, which established Sharia law in Swat.16 Clearly the electoral defeat of Islamic parties in the elections of 200817 has not translated into stemming the spread of Islamization, nor is such a prospect likely in the near future. The state has shaped political discourses in such a way that the ideological demand for Sharia has become, in a sense, an internalized and depoliticized fact of life in Pakistan. Just as the idea of human rights in Western society often cuts across partisan lines and specific dogma, Sharia is increasingly forming a similar overarching narrative in Pakistan.

Nor is the military, even as its own social class,18 immune from such trends or the groundswell of conservative religiosity visible in Pakistani society today. The military has always been at the forefront of the so-called Islamization campaigns, most visibly during the Western-supported regime of General Zia ul-Haq in the 1970s and 1980s, and is the architect of Pakistan’s Islamist direction. Further, Pakistani soldiers imbibe not only a narrow nationalistic ideology common to most militaries of protecting the country’s borders. They are also taught to think of themselves as “Soldiers of Islam,” entrusted with the defense of Pakistan’s “ideological frontiers” as an Islamic state.19 The military’s tell-tale motto, “Iman, Taqwa, and Jihad fi SabilAllah,” (faith, piety, and jihad in the way of Allah) indicates how the Islamist Taliban have played havoc with its ideological moorings.

Pakistan is losing the battle of ideas, and the Taliban have been taking advantage of the state’s contradictions. They have moved beyond being a purely negative force capitalizing on the unpopularity of Western and specifically U.S. policies in Pakistan and Afghanistan, to increasingly advancing a constructive agenda in the areas under their control. Obviously, they have been most vocal about the need for a true Islamic state. But some practical contours are becoming visible past this rhetoric. For example, they have backed an Islamic welfare state in Pakistan that addresses basic services and socioeconomic inequalities. Further, the Taliban campaign leading up to their takeover of Swat fully exploited deep class resentments. All of Pakistan’s traditional power brokers, from the military to mainstream political parties and Islamists, have generally opposed land reform, with the latter viewing private landholdings, no matter how inequitable, to be sacrosanct. In contrast, the Taliban drove out large landowners in Swat and engaged in more egalitarian redistribution of land. They are attempting to follow similar tactics in Buner.

Such actions have gained the Taliban both popularity and legitimacy in the eyes of many belonging to the region’s under-classes. If the Taliban prove earnest in enforcing a redistributive agenda they, or Punjabi militant groups with similar ideologies, may find it easier to make inroads into the Pakistani heartlands where land and income distribution continues to overwhelmingly favor wealthy landowners and the elite. Already, a group calling itself the Tehreek-e-Taliban Punjab (Movement of Punjabi Taliban) has carried out attacks in the province. If this support from the under-classes becomes generalized, the Taliban (or their like-minded allies) will be able to tap into a very large constituency. After all, the vast majority of Pakistanis are poor. According to conservative estimates, 33% of Pakistan’s population of 170 million live below the poverty line, and nearly 75% live on less than $2 a day.

The Taliban are increasingly succeeding in one crucial aspect of an insurgency, as outlined by the renowned Pakistani scholar, the late Dr. Eqbal Ahmad. The Taliban are focusing not simply on outfighting the Pakistani army, but on out-administering the state. They are draining the state’s political and ideological legitimacy while broadening their own.20 This increases the state’s moral and political isolation from the people. Insurgencies succeed when this isolation becomes total and irreversible. 21 Thus, ideological blowback has turned the battle between the Pakistani state and the Taliban militia into a struggle over legitimacy: not just the coercive power to rule but the moral authority to do so. The battlefield isn’t just the rugged mountains of FATA and NWFP, but also the ideological terrain where the struggle for legitimacy is being waged.

Positioning AfPak

The recent U.S. AfPak strategy is complicating matters for Pakistan. Classifying Afghanistan and Pakistan as a single theatre — AfPak — might capture some of the tactical realities faced by NATO troops in Afghanistan. U.S. military planners don’t see any reason to distinguish between different groups that target NATO forces. But conceptually, this may carry significant strategic drawbacks. It will likely lead to more interdependency and cooperation between insurgent groups in the two countries. Failure to distinguish between the Taliban and al-Qaeda resulted in greater cooperation and ideological identification between the two. Strategic failure to distinguish between the Taliban groups operating on either side of the Durand Line may also lead to a similar amalgamation. Indeed, one of the main aims of al-Qaeda propaganda has been the project of convincing the Taliban — in Afghanistan and Pakistan alike — that they are not simply engaged in national struggles but are part of a global war for Islam. Mullah Omar, the reclusive leader of the original Taliban group that took power in Kabul in the 1990s, has similarly called for greater unity between Pakistani and Afghan Taliban. AfPak dovetails nicely with these pan-Islamic notions of a unified struggle.

AfPak so far appears to be a confused and multi-vocal policy. Essentially it’s an escalation of the U.S. war in Afghanistan and its expansion in Pakistan. The recent Pakistani military offensives are part of this strategy. In fact, the United States has been flexing its diplomatic muscle to obtain a guarantee from India to restrain military tensions with Pakistan, which in theory frees up the bulk of Pakistani troops stationed near the Indian border in Punjab and Sindh to focus solely on counterinsurgency operations in NWFP and FATA. The operations in Swat are a stepping stone to the real prize-fight the United States has been urging on Pakistan: pacification of FATA, particularly the inhospitable Waziristan agencies, which are allegedly home to the bulk of al-Qaeda’s regional leadership as well as several top Taliban commanders.

Stepped-up drone attacks on FATA have already killed an estimated 700 civilians (for 14 al-Qaeda leaders assassinated). The United States is considering an expansion of airstrikes into Pakistan proper by targeting Taliban leaders in the province of Baluchistan. Baluchistan has a history of episodic armed rebellion against the central government, as well as a large Pashtun population. The province is already on tenterhooks with ongoing provincial unrest. Any expansion of missile attacks into the province and attendant civilian casualties would have grave consequences for stability in Pakistan.

The trebling in size of a large military base in Afghanistan’s Helmand province, adjacent to Baluchistan, as well as the appointment of General McChrystal as commander of U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan, are also worrisome. McChrystal is an enthusiastic supporter of Special Forces commando raids and “precision” strikes, with all the risks they entail. A recent airstrike in the Farah province of Afghanistan reportedly killed as many as 150 people. His appointment and background in aggressive counterterrorism are good indications that the use of such tactics in Afghanistan and Pakistan will continue. The Helmand base also signals that U.S. presence in the region and operations in Pakistan will expand for the foreseeable future. The linking of U.S. military aid to cooperation in the AfPak stratagem will ensure for the time being that the Pakistani army will remain engaged in internal military operations.

Ultimately, U.S. violations of Pakistani territory, as well as the massive military operations creating millions of refugees, will only further erode the legitimacy of the state and increase its moral isolation. Failing state structures and barters of sovereignty will in turn translate into the political support that sustains long-term insurgencies. This will be especially true if the AfPak escalation entails U.S. ground excursions into Pakistan. U.S. incursions into and bombing of Cambodia in 1973 to clear out Viet Cong sanctuaries were a key factor in the rise of Khmer Rouge. U.S. actions demolished the credibility of the pro-U.S. government and sent many of the millions of refugees into the arms of the guerillas. With the caveat that historical analogies with other countries are most often tricky and imprecise, AfPak may have similar unintended consequences.

A Losing Battle?

If the military is to be believed, its most recent offensive is successfully clearing out Taliban holdouts in Swat. Credible information is hard to come by. But in contrast to its previous military actions, this one enjoys broad support in parliament. There is also a wider social dialogue on the challenge of dealing with the Taliban expansion.

But the military response will not likely sustain this support for long. Unless the army is able to wrap up operations relatively quickly and then hold its gains, the human cost of the offensive (3 million displaced) will quickly sap political and societal support. Already the squalid refugee camps are seething with anger at the military offensive and have turned into ideal recruiting grounds for the Taliban. Because the relief operations are ill-planned, more than 80% of the refugees have not sought shelter at the camps but have migrated, sometimes en masse, to other parts of the country, stoking ethnic tensions in the provinces of Punjab and Sindh in particular. An expansion of the offensive into FATA will further compound these difficulties, particularly as the military and government lumber on without any apparent exit strategy or post-conflict vision.

Still, an unwarranted alarmist tone prevails in the United States, Canada, and many other countries regarding Pakistan. Successful insurgencies against an established and entrenched state — as opposed to a foreign occupier that, by definition, can pick up and leave — require a shift from terrorist and guerilla tactics to conventional warfare. Holding large tracts of land and dense urban centers requires more than a few thousand gunmen. The Taliban will not likely be in any position to stand toe-to-toe with the Pakistani military and its massive conventional arsenal in the foreseeable future. Thus contrived panic in Western capitals over the Taliban nesting in Swat, less than 100 miles from the capital, as well as over the security of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal, is both naively exaggerated and cynically self-serving. The Taliban are not about to sweep into power, and Pakistan’s nuclear weapons have sophisticated controls in place. 22

Such alarmism is geared more toward serving Western needs in Afghanistan and buoying NATO presence in the region than showing any genuine concern for the constitutional regime in Islamabad. They create a pretext and ex post facto justification for intervention and escalating the war in AfPak. At the very least, NATO can blame the morass in Afghanistan on the sanctuaries available to the Taliban in Pakistan, and thereby absolve the occupation forces of much of the responsibility. Cross-border attacks fell by as much as 50% in 2008 while attacks inside Afghanistan are rising, indicating that the problems of the Afghan insurgency can’t be simply attributed to Pakistani support and safe havens.

The struggle against the Taliban in Pakistan is in its earliest phases. As with most insurgencies, it will go on for a long time. The actual threat to the state is not an overnight collapse. The Swat fiasco and Nizam-e-Adl Regulations provide a taste of the Pakistani state’s future management strategies. It’s willing to patch up its legitimacy by pandering to the obscurantist demands of the Taliban and to undercut their momentum by making its own judicial system mirror a rough Sharia justice. The real threat isn’t that the Taliban will take over but, rather, that they might not have to.

Effectively opposing the Taliban isn’t simply a technical or military problem, but a moral and political one.23 Intellectual resistance to the Taliban requires reassessing Pakistan’s state ideology and carefully crafting a modicum of social consensus. It needs a closer alignment of ideological projects with popular political aspirations, with the former subservient to latter. The struggle to define the idea of Pakistan must be brought within democratic space, rather than being imposed from above by a colonial state and its ideological apparatus. An open and sustained public dialogue must take place on the symbolic signifiers of the state, particularly its foundational myths, and on the ways Islam is, or is not, to play a role in its public sphere. Most of all, it requires realizing the democratic aspirations of Pakistan’s long-suffering multitudes, in want of basic services and the necessities of life. Western support in this respect needs to be geared toward strengthening representative institutions and civil society as opposed to Pakistan’s entrenched military and permanent establishment.

Pakistanis in the streets see alternatives. Take, for example, the recent mass movement led by Pakistan’s lawyers. Though often referred to in terms of instability in Pakistan — whereas similar movements elsewhere, even where they are less than organic, are given romantic sobriquets of Rose or Orange Revolutions — the movement clearly highlighted the deep-seated commitment of many Pakistanis to democracy and rule of law. These forces and impulses must be harnessed to provide a new direction for the Pakistani state.

Nevertheless, a consensus on opposition to the Taliban and a reorientation of the state will prove difficult given a Pakistani polity that is increasingly fragmented along political, class, ethnic, sectarian, religious, and urban/rural lines. But “initiating a sustained dialogue on the political issues of who we [Pakistanis] are, where we have come from and where we want to go is crucial.” 24 In the words of one Pakistani analyst, “It’s a question of Pakistan’s identity. Was [Pakistan] created for Islam? This kind of confusion is a threat to Pakistan’s existence as a nation state.”

The crisis in Pakistan is not simply political or military. It involves ideas and identity.

Notes

_________________________________________________________________________

1. ‘Pakistani Taliban’ is not a precise term. This article uses the term to denote any number of different militant Islamist Pashtun groups based primarily in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) or North West Frontier Province (NWFP) that are in conflict with the Pakistani Government. The composition of such groups is constantly in flux. The main umbrella group for the Taliban is the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (Movement of Taliban of Pakistan) led by Baitullah Mehsud. It brings together more than 40 different militant outfits in a loose grouping. See Hassan Abbas, ‘A Profile of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan’, CTC Sentinel, Vol. 1, Issue 2, January 2008.

2. The TNSM is part of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan.

3. The terms “Islamist” and “Islamism” are highly contested. For the purposes of this study, I use the simple definition if Islamism adopted by the International Crisis Group that sees Islamism as synonymous with Islamic Activism. That is, “the active assertion of beliefs, prescriptions, laws or policies that are held to be Islamic in character. There are numerous currents of Islamism in this sense: what they hold in common is that they found their activism on traditions and teachings of Islam…”. See International Crisis Group, “Understanding Islamism,” Middle East/North Africa Report No. 37, March 2005.

4. Selig S. Harrison, In Afghanistan’s Shadow: Baluch Nationalism and Soviet Temptations (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1981), p. 25-26.

5. An authoritative account on the birth of Bangladesh remains Richard Sisson and Leo E. Rose, War and Seccession: Pakistan, India and the Creation of Bangladesh (University of California Press, 1991).

6. On these points see Ian Talbot, Pakistan: A Modern History (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005) and Shuja Nawaz, Crossed Swords: Pakistan, its Army and the Wars Within (Oxford Karachi, 2008).

7. A comprehensive account of these issues is found in Steve Coll, Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (Penguin Press, 2004).

8. On the classification of the Pakistani army as Guardian Army, see Ayesha Siddiqa, Military Inc.: Inside Pakistan’s Military Economy (Oxford Pakistan, 2008), particularly p. 51-54.

9. A good study on this point is Olivier Roy, Islam and Resistance in Afghanistan (Cambridge, 1990).

10. On the impact of this on Pakistan, see Gilles Kepel, Jihad: On the Trail of Political Islam (Belknap, 2002), particularly at p. 143-144.

11. For a good discussion on these issues, see Ayesha Jalal, The State of Martial Rule: The Origins of Pakistan’s political economy of defence (Cambridge, 2008), particularly at p. 49, and Husain Haqqani, Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2005).

12. Mobilizing idenitity here refers to, “the process by which…[a community defined in terms of identity]…becomes politicized on behalf of its collective interests and aspirations”. See Milton J. Esmer, Ethnic Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994), p. 28.

13. On this point see Haqqani, Between Mosque and Military, as well as Nawaz, Crossed Swords.

14. For a good study on these issues, see Haqqani, Between Mosque and Military.

15. The historic high for the religious parties was the 1970 election where they gathered 14% of the popular vote. Since then their electoral support had been in terminal decline till 2002, when their share of the popular vote ballooned to 11%. The machinations of the military government at the time ensured that a coalition of religious parties were in government in two provinces and akin to the official opposition at the centre. Figures are from Owen Bennett Jones, Pakistan: Eye of the Storm (Yale, 2003), p. xvii-xviii. The religious parties received a drubbing in the February 2008 elections. They secured only 7 seats in the 342 seat National Assembly and only 2.2% of the popular vote. See Election Commission of Pakistan, available online at http://www.ecp.gov.pk/NAPosition.pdf (accessed October 2, 2008).

16. The sole exception was the Karachi based Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), whose 24 legislators boycotted the vote in protest. See Irfan Ali, ‘MQM rejects parliamentary approval of Nizam-e-Adl’, Daily Times, April 15, 2009. Available online at http://www.dailytimes.com.pk/default.asp?page=2009�415story_15-4-2009_pg7_8 (accessed April 15, 2009).

17. The religious parties received a drubbing in the February 2008 elections. They secured only 7 seats in the 342 seat National Assembly and only 2.2% of the popular vote. See Election Commission of Pakistan, available online at http://www.ecp.gov.pk/NAPosition.pdf (accessed October 2, 2008).

18. On the emergence of the Pakistani army as a separate class, see Siddiqua, Military Inc., p. 83-111.

19. The idea of being “Soldiers of Islam” and Islamic “ideological frontiers” is often attributed to General Zia. See, for example, Zahid Hussain, Frontline Pakistan: The Struggle with Militant Islam (Columbia, 2007), p. 18. In actual fact it was given voice by the whiskey swivelling General Yahya Khan, Pakistan’s military dictator from 1969 to 1971. See Haqqani, Between Mosque and Military, p. 51.

20. Carollee Bengelsdorf and Margaret Cerullo, ‘Introduction’ in (Eds.) Carollee Bengelsdorf, Margaret Cerullo and Yogesh Chandrani, The Selected Writings of Eqbal Ahmad (Oxford Karachi, 2006), p. 4.

21. See Eqbal Ahmad, ‘Revolutionary Warfare: How to Tell When the Rebels Have Won’, in (Eds.) Carollee Bengelsdorf, Margaret Cerullo and Yogesh Chandrani, The Selected Writings of Eqbal Ahmad (Oxford Karachi, 2006).

22. For a useful overview of Pakistan’s nuclear concerns and controls, see Tariq Ali, The Duel: Pakistan on the Flight Path of American Power (Scribner, 2008), p. 209-216.

23. I draw this theme from Eqbal Ahmad and his insightful writings on revolutionary and counterrevolutionary warfare. See Eqbal Ahmad, ‘Revolutionary Warfare: How to Tell When the Rebels Have Won’, in (Eds.) Carollee Bengelsdorf, Margaret Cerullo and Yogesh Chandrani, The Selected Writings of Eqbal Ahmad (Oxford Karachi, 2006).

24. Author’s conversation with Tasneem Siddiqui, a renowned Pakistani social entrepreneur and activist.