When we think of “resistance,” what mostly comes to mind is guerrilla warfare: Vietnamese closing in on the besieged French at Dien Bien Phu, Angolans ambushing Portuguese troops outside of Luanda, or Salvadorans waging a war of attrition against their military oligarchy. But resistance doesn’t always involve roadside bombs or military operations. Sometimes it is sprayed on a Tehran wall or rapped in a hip-hop song in Gaza. It can be a poem in Medellin, Colombia—arguably one of the most dangerous cities in the world—or come from a guitar shaped like an AK-47. In short, there are few boundaries or strictures when it comes to the imagination and creativity that people bring to the act of defiance.

When we think of “resistance,” what mostly comes to mind is guerrilla warfare: Vietnamese closing in on the besieged French at Dien Bien Phu, Angolans ambushing Portuguese troops outside of Luanda, or Salvadorans waging a war of attrition against their military oligarchy. But resistance doesn’t always involve roadside bombs or military operations. Sometimes it is sprayed on a Tehran wall or rapped in a hip-hop song in Gaza. It can be a poem in Medellin, Colombia—arguably one of the most dangerous cities in the world—or come from a guitar shaped like an AK-47. In short, there are few boundaries or strictures when it comes to the imagination and creativity that people bring to the act of defiance.

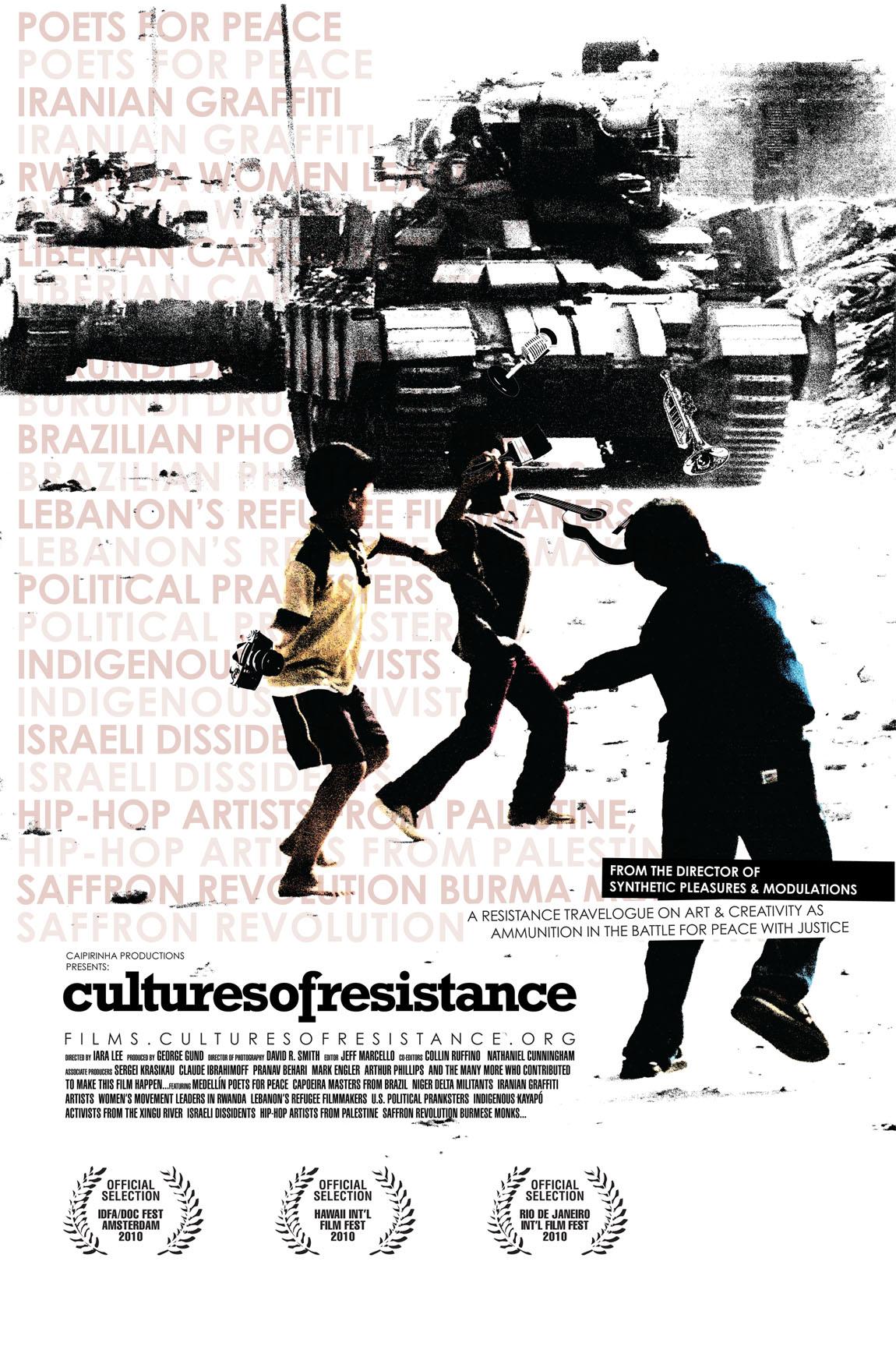

That art can be powerful stuff is the central message that Brazilian filmmaker Iara Lee brings to her award-winning documentary Cultures of Resistance. Her previous films include Synthetic Pleasures, about the impact of technology on mass culture, and Modulations, on the evolution of electronic music. Her most recent film is The Suffering Grasses, about the civil war in Syria.

Lee began Cultures in 2003, just before the Bush administration invaded Iraq, and her six-year odyssey takes her through five continents and 35 countries: Burma, Brazil, Rwanda, Iran, Burundi, Israel, Nigeria, the Congo, and Liberia, to name a few. In each case she profiles a grassroots movement that embodies the philosophy of nonviolent resistance to everything from political oppression to occupation.

Lee, a co-founder of the Cultures of Resistance Network, is a social activist in her own country, where she has aided Amazonian Indians resisting the destruction of their lands and organized against the plague of violence—from both criminals and the police—in Brazil’s slums or Favelas. She is also a member of the Greenpeace Foundation, a member of the advisory board of the National Geographic Society, and a part of the worldwide campaign to ban cluster munitions.

She was also on the MV Mavi Marmara in 2010, the Gaza-bound Turkish ship boarded by Israeli commandos. Nine human rights campaigners were killed in the confrontation, and Lee’s crew managed to smuggle out video footage of the incident. However, U.S. media outlets refused to air it. Lee’s view of the world is not the sometimes distant lens of many documentarians, but the prism of an activist.

Cultures is a surprising film. Lee is a strong supporter of nonviolence, but Cultures of Resistance is not about how hugs will free us all. She recognizes that resistance in the face of oppression—or indifference—can spark anger. The film begins with a remarkable segment on the Amazon’s Kayapo tribe resisting the construction of the Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu River. At one point the Indians’ frustration boils over and they attack an Eletrobras official with clubs and machetes, tearing off some of his clothes and sending him off in bloody retreat. The unspoken point of the segment is that if nonviolent resistance is ignored, things can turn ugly.

This is a lovely film. But there is darkness in it as well, some of it quite disturbing. Racks of skulls line a hut in Rwanda, where some 800,000 people were massacred in 1994, and a deserted church in that country is filled with piles of clothes, invoking the memory of Auschwitz and Buchenwald. But the message of the segment is not death, but life, and how post-genocide communities are coming together to rebuild.

Many of the profiles come from Africa, such as Nigeria, where local people are up against international oil cartels and their own corrupt government. But Lee casts her nets widely. The “Tehran Rats” are graffiti artists who wage clandestine war with spray cans in Iran. Hip-hop artists in Israel say they “sing rap for people who don’t listen to rap.” Poets from around the world gather in Colombia: “Poetry does not overthrow governments, but it does open consciousness and hearts,” one poet says.

Lee has an eye for beauty and drama. Cultures has a clear point of view, but it is not overly didactic, preferring to use juxtaposition and interviews—and lots and lots of good music—to make its points. A simple black and white shot of a young child holding a semi-automatic pistol does a much better job of highlighting the problems of violence in the favelas than would some expert pumping out numbers. Lee first gets the viewers attention through the art. Information follows.

One of the film’s messages is that cultures of resistance—those that have the audacity to say “no”—have things in common. Leadership is not something that resides in one group of people or in a given country, but is everywhere that people dig their heels in and fight back. The Buddhist monks that challenged the military dictatorship in Burma share common ground with the Occupy Wall Street movement. Israelis opposed to the occupation of Palestinian lands, and Palestinians resisting the spread of Israeli settlements, meet in the medium of rap.

“We don’t have planes, missiles, or white phosphorous” Lee told journalist Lisa Mullenneaux, “but we have our freedom to resist oppression. To sing, dance, and express how we feel about world politics. Global solidarity is the only thing that can promote real change.”

“If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be in your revolution,” Emma Goldman famously said. For Iara Lee, meanwhile, dancing can be revolution.