Originally published in The Mantle.

Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010)

I didn’t expect that Shepard Fairey would become a thread tying together three artistic presentations one recent, sunny Saturday. Yet there he was, in full force: in the form of his major, solo exhibition in New York; a couple of hours later his portrait of Burmese political activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi was given to me by a performance artist; and finally, Fairey played a significant part in the street artist film Exit Through the Gift Shop.

Shepard Fairey may have been a recurring artist over three exhibits on May 15, 2010, but the political threads that ran through each of the presentations were more exciting. “Revolutionary” was the theme du jour. Shepard Fairey’s show is a portrait gallery of revolutionary figures; Chaw Ei Thein’s tortured performance cried out for imprisoned revolutionaries in Burma; and Banksy, the producer of Exit Through the Gift Shop, is a revolutionary figure in the shadowy world of street art.

King of Pop

Not long ago, Shepard Fairey was best known for OBEY GIANT, a thematic, repetitive street art project plastered, pasted and painted the world over. Many credit Fairey’s nearly two-decade guerilla urban art campaign for changing the way the general public views street art. For better or for worse, however, Fairey is now best known for his “HOPE” portrait of then presidential candidate Barack Obama, an iconic image that will never be divorced from the 44th president of the United States. “HOPE” catapulted Fairey into the global spotlight, bringing his street art from the alleys to the galleries. (It also landed him in a row with the Associated Press, from whose photograph Fairey lifted Obama’s likeness.) Whereas his ubiquitous OBEY GIANT images are printed for pennies on the dollar and are pasted far and wide for any urban dweller to see, Fairey’s portraits in his “May Day” exhibit sell for tens of thousands of dollars. For modern art collectors, Fairey is a must-have.

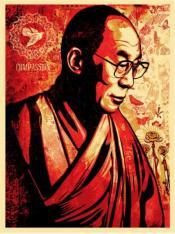

“May Day” launched on May 1st, or International Workers Day. Of the subjects of Fairey’s latest project, he explains, “these people I’m portraying were all revolutionary, in one sense or another. They started out on the margins of culture and ended up changing the mainstream.” And so, we find in his latest offering of a motley collection of portraits: His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Cornel West, Aung San Suu Kyi, Jasper Johns, Keith Haring, Muhammad Ali and Woody Guthrie, to name but a few. Don’t expect any “wow” moments, however. All the portraits are done in the same style of the iconic “HOPE” image—striking colors and shadows and repetitions of patterns penned in by bold lines color easily recognizable visages. Taken as a whole, “May Day” presents an impressive gallery, but the lack of surprises from portrait to portrait soon dulls the viewing experience. Once you’ve seen “HOPE,” it is not difficult to guess at what the Dalai Lama’s portrait might look like. “Political pop art” seems to nicely sum up the exhibit.

Of the subjects of Fairey’s latest project, he explains, “these people I’m portraying were all revolutionary, in one sense or another. They started out on the margins of culture and ended up changing the mainstream.” And so, we find in his latest offering of a motley collection of portraits: His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Cornel West, Aung San Suu Kyi, Jasper Johns, Keith Haring, Muhammad Ali and Woody Guthrie, to name but a few. Don’t expect any “wow” moments, however. All the portraits are done in the same style of the iconic “HOPE” image—striking colors and shadows and repetitions of patterns penned in by bold lines color easily recognizable visages. Taken as a whole, “May Day” presents an impressive gallery, but the lack of surprises from portrait to portrait soon dulls the viewing experience. Once you’ve seen “HOPE,” it is not difficult to guess at what the Dalai Lama’s portrait might look like. “Political pop art” seems to nicely sum up the exhibit.

Not to say “May Day” doesn’t have its sparks. For one, Fairey is an astute collage artist. His political-pop portraits consist of layers of newspapers with strategically placed headlines or excerpts deliberately exposed to the viewer. In the John Lennon and Yoko Ono portrait, for example, the headline “War is Over” is easily discerned amongst the mishmash of newspaper cuttings. And a direct reference to one of the philosopher’s discussions on love between all races, “Justice is what love looks like…” is readable above Cornel West’s three-quarters image.

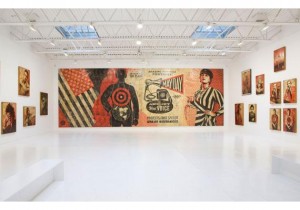

The most striking element to Fairey’s exhibit, however, has nothing to do with the “revolutionary” characters in his portrait gallery, but the revolutionary spirit coming through loud and clear in his striking, ten-foot tall triptych in which a megaphone is advertised to “project free speech great distances” (but even that megaphone comes with a price—$89.95).

Keeping it Real

From the posh galleries of SoHo to a warehouse district in Brooklyn, where the New York Artist Residency and Studios (NARS) held an open studio event. The crisp lines of the Deitch Gallery where Fairey’s art hung precisely gave way to a warren of studios where artwork was slapped haphazardly across dilapidated walls or was strewn about floors like someone was feeding art-hungry pigeons. The main draw of this event, in which close to fifty artists were on display, was Burmese political artist Chaw Ei Thein.

Unlike Fairey, Chaw Ei mixes up her artistic runs, the only thing common between them being the political weight they carry. (Aside performance art, she’s a painter and a sculptor.) In previous performances around the world she has closed herself off in small black boxes with only a small hole from which to gasp for air and pass notes filled with political messages to passersby, and she has wrapped herself in black cloth to squirm and blindly paint the cry, “What next, Burma?” in the last blank spot of a mural of Burmese political life. Moreover, in her performances Chaw Ei remains mute (minus the painful moans that may come naturally from physically difficult exhibitions). In Brooklyn she once again delivered a quiet, powerful, and moving performance. And once again, the politics of Burma weighed heavily in the still air.

A few years ago, Chaw Ei, a native of Burma now living in exile in the United States, was detained in her home country for five days for a public art performance that crossed the line (she was selling trinkets in the street, a no-no in their strict market environment). Later, she helped smuggle artwork from an imprisoned artist for a gallery show in London. Since then, she’s given politically motivated performances in Thailand, Singapore, Canada, and Japan. In the U.S., her political streak continues.

At the NARS open house event, Chaw Ei incorporated torture into her newest performance piece. Taking inspiration from political prisoners in Burma, many of whom are her friends, her performance was a moving, if at times uncomfortable, tribute to those forced to endure torture back home. “I listened [to] their experience, and then try to imagine how their body will work,” the artist said of the performance. Chaw Ei would request that the victims mime their torture positions, positions which were replicated in her art.

Chaw Ei came into the performance space hooded, hardly able to see or breathe, barefoot, her hands held behind her head. Variously she mimicked torture and stress positions forced upon the unlucky back home. Soon enough Chaw Ei was on her hands and knees, forcefully plunging her hooded face into food (force feeding?) and into a bucket of water (simulated drowning). A bar strapped between her ankles prevented her from walking and moving comfortably throughout the performance.

At the end of her exhibition, Chaw Ei, still mute but visibly exhausted (and wet), stumbled around the perimeter of the space, passing out propaganda to each of the audience members.

At the end of her exhibition, Chaw Ei, still mute but visibly exhausted (and wet), stumbled around the perimeter of the space, passing out propaganda to each of the audience members.

Here is where Shepard Fairey reappeared. Along with the Burmese dictate (Section 225), which stipulates penalties for coming to the aid of someone being detained by police, Chaw Ei passed out Fairey’s bold, inspiring portrait of the venerable Aung San Suu Kyi. In Fairey’s work, the disenfranchised political leader’s visage glows, indicating a much more hopeful image than the famous Obama portrait, and much more triumphant than the tired face of the consistently dramatic artist, Chaw Ei.

The Joke’s on… ?

Onward, then, to a screening of the film, Exit Through the Gift Shop, in which, you guessed it, Shepard Fairey plays a starring role. This film is fascinating for two reasons: first, it presents an extremely rare, inside-look at an underground cultural movement sweeping urban landscapes worldwide. Second, halfway through, the narrative of the film turns in on itself (or its protagonist), flipping the script from a glimpse at street artists in their element to the manufacture of a pseudo-street artist, known as Mr. Brainwash.

Exit Through the Gift Shop begins innocuously enough.

The premise, we are misled to believe, centers on French filmmaker Thierry Guetta ‘s obsession to film the shadowy art scene known as street art. Lucking onto the street artist known as Space Invader, Guetta quickly gets sucked into this exciting world, spending much of his time filming every achievement (and misstep) of street artists like Space Invader, Shepard Fairey, and many more around the world. His mission can only be completed, however, after he meets Banksy, arguably the most famous street artist out there. This is only half the story, though. Midway through Exit, the narrative suddenly turns on itself. Thierry becomes so enamored by the street art world that he decides to become a street artist himself. Adopting the moniker Mr. Brainwash (M.B.W. for short), Thierry emulates his artistic mentors and begins plastering his images wherever he can find a blank wall. Unsatisfied with his obscurity, however, he schemes to take over the street art world by manufacturing not only an identity, but hundreds of art works (a collection that pretty much plagiarizes the styles of everyone from Andy Warhol to Banksy) for an unprecedented, over-the-top, exhibition in Los Angeles.

In a twist that really makes this documentary unique and unexpected, Banksy, who produced the film, turns the cameras back on M.B.W. and a mushrooming, gullible art world taken in by this great new artist and snatching up pieces manufactured (literally, in assembly-line fashion) for tens of thousands of dollars at a time.

“Suckers,” Banksy appears to be saying with Exit, with a shake of his head in dismay at the rise (and fall?) of a once-sacred, now co-opted, commercialized, commodified street art scene. And, well, considering that I had just seen Fairey’s work on display in SoHo, also selling for tens of thousands of dollars at a pop, and that Banksy’s own work is making him richer than he ever dreamed, he’s got a point.

The title of the film itself presents an economic critique. By the end of the Exit, Banksy seems more and more frustrated, annoyed, and, well, pissed off at Mr. Brainwash. M.B.W. skipped right over the heavy-lifting every other street artist has had to endure. Fairey spent twenty years pasting his OBEY GIANT material around the world. Space Invader labors in the shadows pasting his pixilated images across Europe and even causing a stir outside Boston where one of his pieces was mistaken for a bomb. Banksy has endured praise and ridicule for his public art in London, New Orleans, New York, and everywhere in between, including the massive wall separating Israel and Palestine. And yet here comes M.B.W., able to leap to the top of the art world with a manufactured identity and product, and able to dupe an insatiable art collector world into purchasing the “art,” as if they were shopping at a gift shop.