This is my third and final post about a paper written March 2015 titled Failure to Protect: Syria and the UN Security Council by Dr. Simon Adams, Executive Director of the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, a project of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies of the Graduate Center, City University of New York. Let me begin by acknowledging that the United States bears a lion’s share of the blame for the state of Syria today because its invasion of Iraq turned the whole Middle East upside down.

But, at the risk of repeating what I wrote in the previous two posts, today much of the blame for failing to help end the devastation of Syria lies with Russia and China. They vetoed United Nations Security Council draft resolutions holding the Syrian government accountable for crimes against humanity. As I quoted him in both of my previous posts on his paper, Dr. Adams wrote:

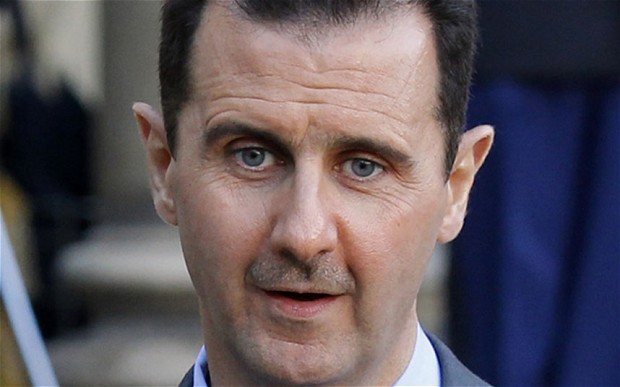

With each failure of the Security Council to hold the Syrian government accountable for its actions, President Bashar al-Assad’s forces deployed more extreme armed force. This, in turn, strengthened the most uncompromising and severe elements within the armed opposition, especially those with external sources of sustenance. The net effect has been to turn Syria into the world’s worst case of ongoing mass atrocities, civilian displacement and humanitarian catastrophe.

Vetoes such as these abnegate the raison d’être of the Security Council and make a mockery of the reasons it was created. Dr. Adams:

When the Security Council first met in London during January 1946, with Europe still in ruins as a result of World War II, its intended purpose was to not only guard the peace and stability of the post-war order, but to protect the weak and vulnerable. The baleful shadow of Auschwitz loomed over the formation of the United Nations, directly influencing two of its early impressive achievements – the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, adopted on successive days in December 1948.

“Syria,” Dr. Adams continues, “has brought into stark relief the reality of a twentieth century UN struggling to respond to twenty-first century challenges.” In fact (emphasis – and extra-emphasis – added):

The use of the veto in a mass atrocity situation is inconsistent with the aspirations of a 193-member General Assembly that no longer believes that sovereignty should constitute an unrestricted license to kill. … In particular, there is growing pressure to uphold the UN’s 2005 commitment to prevent genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and ethnic cleansing. … Issues relating to humanitarian access, negotiating a political solution and ending impunity for mass atrocities remain complex and fraught with political danger. But the inability to successfully resolve any of them after four years of conflict constitutes a catastrophic historic failure on behalf of the Security Council.

It’s tough to disagree with this:

The cruel truth is that there is no easy solution to the suffering of the Syrian people, but that does not mean that the Security Council has to choose between invasion and inaction.