The capacity of sports to contribute to social change must not be overstated but history has proven that possibilities for change do exist. Sports have changed individuals’ lives and, more importantly, contributed to and facilitated larger social change within and across societies.

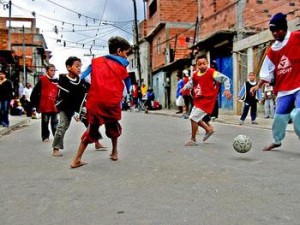

Photo by Carf.

While it’s easy to get swept up in the commercialism at major sports events, one shouldn’t ignore the transformative capacity of sport to produce social change. Historically, the potential for sports lies not with the values they promote, since they are invariably unjust and uneven. Instead, the possibilities that exist within sports are those that bridge divides between societies with radically different views of the world.

International sports events offer opportunities to foster trust, stress international obligations, and promote a shared respect for sports. While many politicians wish to separate sports from politics and social change, ignoring the capacity for sports to help bring about social change isn’t an option for policymakers and the world of sports itself.

Sports, Aid, and International Conflict

The Norway Cup has taken place every year since 1972. It’s one of the world’s largest soccer tournaments for children. Every year more than 25,000 kids play in the Cup. The aim of the tournament is to create bonds between participants across nations through education and sports, a foundation of friendship between clubs from the West and particularly poorer areas of the world such as parts of Africa. The Norwegian Minister of International Development values the role that such a project plays in “producing internationalism and co-operation between Norway and many other countries such as Brazil, Kenya, and Palestine.” In 1998 1,325 teams from 34 nations played 3,500 soccer matches on 49 fields.

Norway’s placement of sports within its international development portfolio signifies a shift in emphasis within the international development assistance agenda. The organization, Right to Play was founded in Norway in 1994 (originally as the organization Olympic Aid) as part of the legacy of the Lillehammer Winter Olympic Games. The strategic objectives are to use sports and play programs to improve health, develop life skills, and foster peace for children and communities in some of the most disadvantaged areas of the world. Right to Play raises funds to support its programs from governments, foundations, individuals, and from members of the Olympic Movement including: athletes, the International Olympic Committee (IOC), National Olympic Committees (NOC), organizing committees of host countries, and corporate partners.

Outside the role of providing aid, sports have supported peace building. The concept of an “Olympic Truce” is noteworthy in terms of recognising the role of international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in influencing and brokering international relations. An Olympic Truce was launched on January 24, 1994 for the period of the Lillehammer Winter Games in an attempt to resolve the conflict in Yugoslavia. This Olympic Truce involved representatives from the World Health Organisation (WHO), UNICEF, the Red Cross, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and the Norwegian Government. These groups evacuated coaches, athletes, and members of the national Olympic committee from Sarajevo so that they could compete in the Games.

In 1998, during the Nagano Olympic Games, the observance of the Olympic Truce allowed the UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan to intervene to seek a diplomatic resolution to the crisis in Iraq. At the 2004 Athens Olympic Games, North and South Korea marched under the same flag of the Korean Peninsula. Given the success of the truce movement, the issue is permanently on the agenda of the UN General Assembly in the year prior to an Olympic Games. The UN flag also flies at all Olympic Games competition sites.

In a number of ways sports have long offered a means of social intervention and welfare aimed at supporting people who have been traumatized by conflict; in the promotion of programs of conflict resolution, and by helping in situations of military conflict where sports are used to draw people out of routines of violence.

The Twic Olympics which have been staged in Twic County (Sudan) since 2000 are aimed at encouraging a moment of tolerance and compassion in an area of the world which has experienced conflict for more than half a century. For nations competing in this year’s 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, the Twic Olympics offer a surreal parallel.

At the opening ceremony, each district has a flag bearer at its head, carrying a homemade banner with stars, or leopards or bulls crayoned on it. Behind them march the athletes and an effort is made to keep colours uniform within each district. Few in Sudan can afford to choose their clothes with care, few of the athletes wore shoes and yet the significance is not the dress of the athletes but that it’s taking place at all. Each January, teams of athletes gather to compete at soccer, volleyball, dance, athletics, and tugs of war.

The competitors are full of people like “James” who was drafted into the army at the age of 11 and doesn’t smile. He points out that even in playing sports, “nothing is normal for us.” At the end of the Twic Olympics the district with the most medals is declared the winner with the prize being a mechanised flour grinding mill. In a country with few roads or even brick buildings such forms of capital are worth competing for.

In part, the benefits from using sports as a development tool or for peacebuilding involve not just athletics but more importantly, education through sports. Such programs have long since been viewed as agents of social change for individuals with the rationale being that they can:

- Provide opportunities for life-long learning and sustain not just education but an involvement in sports and physical activity;

- Increase knowledge and skills and in a broader sense contribute to the knowledge economy;

- Foster social capital through building relationships, networking, and making connections;

- Encourage critical debate about key public issues; and,

- Support development programs across the world that use sport as a tool or incentive for participation.

It’s the ability to combine sport with other social forces such as education through sport that has facilitated an increased profile for sport by UNICEF, UNAIDS, and WHO.

Promise and Possibilities

Historically sports and education have been key avenues of social mobility and an escape from poverty for some. Thinking systematically about emancipatory alternatives, the part played by sport is only one or element in the process by which the limits of the possible can expand and the promise and possibilities of the power of education through sport can increase for more people.

Improving life chances requires a coordinated effort and as such any contribution that sports can make must also build upon a wider coalition of sustained support for social and progressive policies. The life chances approach to narrowing the gap between rich and poor has a key role to play in producing social change. It requires harnessing a strong political narrative and action plan that fits with many people’s intuitive understanding that life should not be determined by socio-economic position and that people do have choices, whilst drawing attention to the fact that some people and places face greater risks and more limited opportunities.

Many African runners have provided an exhilarating spectacle for global audiences but what’s often forgotten is that the money raised from these performances often provides pathways of hope for other people. Maria Mutola, the Mozambican former Olympic and five-time world indoor 800m champion and world record holder, routinely sends track winnings back to her country. Chamanchulo, the suburb of Maputo in which Mutola grew up, is ravaged by HIV, passed on in childbirth or breast milk to 40 percent of the children. In 2003 when Mutola became the first athlete to collect $1million for outright victory on the Golden League Athletic Grand Prix Circuit, part of the cash went to the foundation she endowed to help provide scholarships, clothing, education, and coaching for young athletes. Farms and small businesses have often been sustained by her winnings on the circuit, which have purchased tractors, fertilizer, and equipment to drill small wells.

In part the promise and possibilities of sports are encapsulated in the words of the former Olympic and Kenyan athlete Kip Keino who said in an interview with the author in 2007 that:

I believe that sport is one of the tools that can unite youth. Sport is something different from fighting in war and it can make a difference. We can change this world by using sport as a tool.

I’ve run a lot for water charities and children’s charities. I believe we share in this world with members of our society who are less fortunate. This is important. We came to this world with nothing and we leave this world with nothing. So we can be able to make a better world for those who need assistance.

Transformative Power

The late writer Susan Sontag commented that any novel worth reading was an education of the heart in that it enlarged your sense of possibilities and of what human nature had the capacity to do. She was fervent believer in the capacity of art to delight, to inform and transform the world in which we live. Such arguments are readily accepted about the arts but they need also make sense in relation to other areas of social life such as sport and in particular the possible capacity of sport to fulfill its potential and to enlarge one’s sense of human possibilities, to delight, to inform and ultimately help to transform the world in which we live.

Catherine Astrid Salome Freeman became the first Aboriginal to represent Australia at the Olympics, at Barcelona in 1992 and became its first world champion and first Olympic champion. In doing so she became a symbol for reconciliation between a black and white Australia. Her grandmother, Alice Sibley, was one of the members of the so-called “stolen generation.” She was taken from her parents at the age of eight by a reviled 1950s Australian government policy that removed Aboriginal children removed from their parents and resettled them with white families

Her Olympic success has perhaps helped to change the face of prejudice, almost a taboo subject in a modern Australia. Her Olympic reception following victory in the final of the 400-meter dash may be viewed in stark contrast to the day she travelled to a meet at age 13. Waiting outside Melbourne’s Flinders Street Station, she was ordered to move on by a group of middle-aged white housewives, when the whole adjacent seating area lay vacant. As Cathy Freeman held the Olympic torch aloft during the opening ceremony of the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games she did so in an allegedly different Australia from the one experienced by her parents. She herself had become perhaps one of Australia’s greatest sporting icons but also a symbol of the struggle that aboriginal Australians had to endure in order to win social, civil, and political rights.

Conclusion

The truth about global and Olympic sports as a universal creed is that they are also an engine of injustice. The social dimension and possibilities of sports remain as empty slogans, and constant historical reminders proclaiming the principles of equality, justice, and the eradication of poverty have not sufficed to make a reality of it. Sports need to be more just and less charitable. But they continue to provide a pathway for hope for some in different parts of the world.

As the international sports calendar unfolds each year and the spectacle of the Beijing Olympics is followed by the Soccer World Cup in South Africa (2010), Commonwealth Games in Delhi (2010), and the London Olympics (2012), it’s worth remembering that while there is no single agent, group or movement that can carry the hopes of humanity alone. There are many points of engagement through sports that offer good causes for optimism that things can get better, not just for individual athletes or communities, but for the entire world.