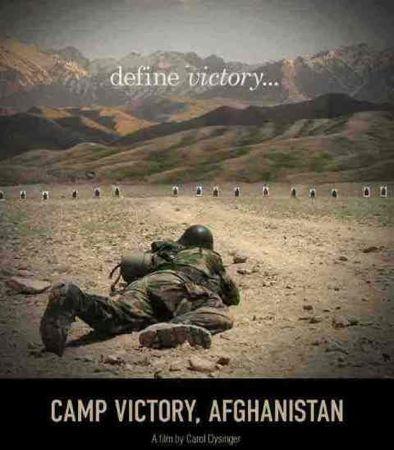

“All I need is 100 loyal Afghan men, and we could defeat the Taliban.” This is the first we hear from Afghan General Fazalulin Sayar in Carol Dysinger’s documentary Camp Victory, which opened in New York this past weekend as part of the Human Rights Watch film festival.

“All I need is 100 loyal Afghan men, and we could defeat the Taliban.” This is the first we hear from Afghan General Fazalulin Sayar in Carol Dysinger’s documentary Camp Victory, which opened in New York this past weekend as part of the Human Rights Watch film festival.

The film traces the relationship between Sayar — an earnest commander whose commitment and fatigue show in the two deep grooves that run from his eyes to his mouth — and his gaggle of American advisors from the National Guard who have come to Camp Victory in Western Afghanistan. The Americans are there to help Sayar turn a ragged bunch of young Afghan men into an effective fighting force.

The documentary chronicles the development of Camp Victory from 2004 to 2009, during which Sayar’s claim to need only 100 men to defeat the Taliban becomes increasingly problematic. The problem isn’t that the general overstates the capability of the Afghan soldier. Instead, he reveals the difficulty of recruiting and maintaining even a modest number of quality soldiers in his ranks. The challenges that Camp Victory has faced stand in for the difficulty of the U.S. coalition strategy overall in Afghanistan.

The Rise of the ANA

Afghan President Hamid Karzai launched the Afghan National Army (ANA) in 2002 to supplant the domination of the country by local warlords. Putting Afghan security forces in charge of the war against anti-government Taliban extremists has been and remains a key pillar in the U.S. and NATO counterinsurgency strategy in the region. Indeed, the success of America’s war in Afghanistan hangs on the Afghan army. “The Afghan National Army can solve the problems of the Americans,” said Afghan Colonel Akhbar in 2003, but “until the Afghan National army is built, there will be no security in Afghanistan.”

Building a national military in a hurry is a heavy task, and the battle record of the Afghan troops trained at Camp Victory offers few encouraging signs. In 2006, the company faced heavy firefighting in Lashkagar. As Dysinger’s film reports, a few Afghan soldiers fled and many more took a backseat to the all-night shootout that left an American medic dead. Unfortunately, Sayar’s men are no exception. Despite the emphasis the U.S. and coalition forces have placed on the ANA in the overall counterinsurgency strategy in Afghanistan, the Afghan soldiers have performed poorly on the battlefield.

In the Taliban stronghold of Marja, where fighting was heavy this past spring, ANA forces were nominally in charge. But, as CJ Chivers reported in The New York Times, American officers and troops were clearly leading the battle in a “city” with a population of only 50,000. On June 7, Afghan security forces were unable to prevent an attack on a police training center in the southern city of Kandahar that killed two American security contractors. The incident doesn’t bode well for the much-anticipated and now-delayed Kandahar offensive.

Understanding the Shortcomings

Why is the Afghan army proving to be such a disappointing fighting force? Most of the news and official government reports have tended to frame the problem in technical terms. Chivers, who reported on the shortcomings of the ANA in Marja, did a series of video stories this past spring that focused on the poor marksmanship of Afghan soldiers who point their Kalashnikov assault rifles from their shoulder rather than holding the sights to their eyes so they can actually aim at the targets. For its part, the Pentagon has underscored the low salaries of infantrymen, the lack of trained officers and mid-level leaders in the ANA, and a dearth of available trainers from the coalition forces.

Focusing on these gaps in the capacity and technical abilities of the ANA, which do exist, can be misleading. Take the issue of salary, for instance. According to Dysinger’s film, at $66 a day, the salary for new recruits at Camp Victory was already more than double what these young men, most of whom grew up in refugee camps in Pakistan, could expect to earn elsewhere. And while these soldiers may be poor marksmen when they enter the army, it isn’t clear why they remain so after months of training. “It is not difficult to turn a religious student into a religious fighter, capable of using light weapons,” says former Afghan defense official Haroun Mir. Surely, the Afghans, who have been at war for the last 28 years, and who have fought foreign occupation for hundreds of years before that, are not inherently lacking in military skills. One doesn’t have to romanticize the Afghan warrior to concede that the technical ability should come fairly easily, so long as there is a will behind it.

Perhaps the more important question is not whether the Afghans can fight, but whether they actually want to fight. One of the more illuminating scenes in Camp Victory shows a line of new recruits looking apathetic and somewhat bewildered as their American advisors direct them through the physical training exercises. The shout, “Come on, one more push-up!” from the American trainers is met with a good-humored laugh followed by no thank you. If this were a U.S. feature film, Jack Black, not Richard Gere, would play the part of the new recruit.

The National Guardsmen in Camp Victory respond to the lethargy in their trainees with a considerable amount of patience and understanding. Elsewhere in Afghanistan, some American advisors have been less successful at keeping their frustration and anger at bay. A March 2009 video of Marines serving as embedded tactical trainers (ETTs) in Afghanistan shows U.S. soldiers chastising their Afghan counterparts, who prefer to smoke hashish rather than prepare for inspections and ready themselves for the day’s mission tasks. At one point, an American trainer, speaking to his Afghan counterpart over walkie-talkie, says, “I don’t give a fuck about your chai, I care about the mission,” an exchange that obviously upsets the Afghan interpreter in the middle.

Echoes of Iraq

This scene is far tamer, but reminiscent of amateur footage from Iraq (the place and date are not reported) in which a U.S. soldier curses out a group of Iraqi police trainees. “I come down here to try to train you, and you’re fuckin’ trying to kill Americans. You’re trying to kill your fellow fuckin’ Iraqis.”

Differences in tone notwithstanding, one common thread that runs through the frustration of American trainers in Afghanistan and Iraq is their emphasis on loyalty to nation. The American soldier in Iraq is so angry because he suspects that a good portion of the men standing before him have been working for the Mahdi militia and not the Iraqi nation. “You guys better figure out where your loyalties lie. Are you loyal to Iraq? The Shia? The Sunni?” With much less ire but a similar message, the American officer in the Guardian video tells his demoralized Afghan counterpart, “You need to figure out what motivates your soldiers. You need to get that sense of nationalism.”

In fact, in several recent conflicts, it’s not just the fighting ability of Afghan soldiers but also their loyalty that has come into question. Last November, an Afghan police officer opened fire on his British colleagues in Helmand province, killing five. In January, a suicide bomber wearing an Afghan army uniform carried out an attack on a NATO base in Khost province. These incidents suggest that Afghan insurgents have infiltrated the ANA, and perhaps more troubling, that some soldiers are playing on both sides of the war.

Perhaps the question isn’t why the average soldier isn’t loyal to the ANA, but rather why should he be? The attitude of the average Afghan toward the central government is decidedly ambivalent. There isn’t much evidence that the U.S. counterinsurgency strategy has been effective in decisively turning people against the insurgency.

Rising Insurgency?

Buried in a sea of updates on U.S. and NATO organizational streamlining in the Defense Department’s recent progress report on Afghanistan is the stark admission that 2009 was a good year for the insurgency, which has been gaining support among the Afghan populace. Of the 121 areas deemed strategically critical to the U.S. strategy in Afghanistan, only 29 have populations that support the Afghan government. Since that’s a declassified Pentagon statistic, the reality may be even worse. In line with its entire report, the Pentagon frames its response to the problem in terms of capacity-building and technical improvements, in this case using the language of governance. “ISAF [International Security Assistance Forces] is working closely with the Government of Afghanistan and the international community to coordinate and synchronize governance and development in the 48 focus districts prioritized for 2010.” Meanwhile, as the same report notes, the insurgency is increasing its own capacity to act as a shadow government, in some areas already doing many of the same things that the central government now only plans to do.

Just as the United States can’t build Afghan nationalism solely through closing capacity and technical gaps, neither can it foment nationalism in the military solely through army training. Consider the U.S. experience by contrast. Although the U.S. military has surely played an important role in fostering and perpetuating nationalism, it was not by any means the initial source of national feeling, which bubbled up from a complex web of economic, political, and cultural forces. Occupied as much by internal strife as by foreign invaders, Afghanistan has little basis on which to build a national feeling. At Camp Victory, the infantry soldiers march to the words, “Oh country, I’ll sacrifice my life to defend you!” It is as though they are singing a song in a foreign language.

Meanwhile, after target practice, local villagers scramble to pick up artillery shells to sell them to the highest bidder. Like the Afghan infantry soldier, these villagers still do not have a lasting reason for being anything but fence-sitters. And it is still not clear how the U.S. counterinsurgency strategy will change a government or a people whose attitudes and behaviors toward each other have complex historical and social roots that cannot be fully addressed through capacity-building and technical improvements.

For Want of 100 Men

If there ever were a true Afghan patriot, General Sayar would qualify. Ever since the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, he looked to the United States to help his country. In the 1980s, while serving in the Soviet-run Afghan army, he had close contacts with the U.S.-supported Mujahadeen and its leader Ahmad Shah Massoud. On January 14, 2009, Sayar’s helicopter crashed in Adraskan district of Herat province in Western Afghanistan. Colonel Shute, Sayar’s American advisor, was devastated when he heard the news and wondered how the United States had let such a high-ranking general get on an outdated clunker of an aircraft that no American would board. Sayar saw America as his country’s hope, and America let him down.

It’s not clear whether the film wants us to see this tragedy as the story of a lost victory or that of a lost cause. The ambiguity stems in part from Dysinger’s choice to explore the larger problems facing the ANA through the lens of Sayar’s relationship with Shute. This gives Camp Victory a human quality and makes for a compelling personal story. Both Sayar and Shute are honorable and intriguing individuals who were able to forge an unlikely, intimate, and loyal friendship. At the same time, this story of camaraderie between two officers, one of whom is American, takes the focus off of the Afghan infantry soldier whose bond to the country of Afghanistan is ultimately the most important and tenuous of all.

Camp Victory ends with Sayar’s death, which occurred before the Obama administration escalated its commitment to the war in Afghanistan. Over the last year and a half, the effort to build up the ANA has become even more of an urgent priority, in line with the Obama administration’s plan to begin withdrawing American troops in mid-2011. In January 2010, the Pentagon announced the “acceleration” of the ANA training program. Under this plan, the Afghan army would increase from 102,400 personnel to 134,000 by October 2010 and 171, 600 by October 2011. The goal is to grow the Afghan army to 400,000 by 2013. With the United States as primary bankroller of the ANA, Congress has appropriated $6.6 billion dollars for the task. According to the Defense Department’s most recent report card on Afghanistan, recruitment levels are up and on schedule to meet these targets. So many soldiers and so much money, but still the question remains: Can they get 100 loyal men?