Russian President Vladimir Putin has said that Russians and Ukrainians are brothers but that Ukrainians have been brainwashed. Following this reasoning, the Kremlin is sending allegedly clear-headed and well-informed Russian soldiers to fight their poor, brain-damaged brothers and sisters. It’s not a very pleasant picture—and it’s also nothing new. In many ways, the current conflict repeats an earlier tragedy involving one of Ukraine’s most important anarchists.

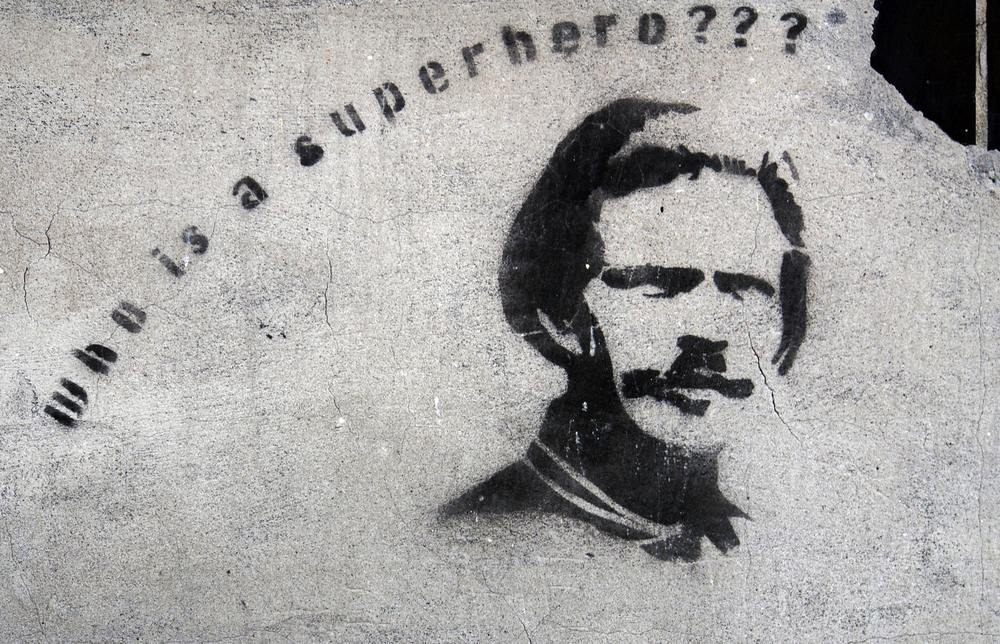

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno was born in Huliaipole, which is situated in the same province as the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power station. Until 1921, Makno took part in many of the battles in that region. First, he faced Germany and its allies in World War I, followed by the reactionary Russian White Army. Then he fought the government in Kyiv before, finally, the Red Army vanquished the Makhnovshchina and forced Makhno into permanent exile.

In the first stages of the Russian revolution, however, Makhno was seen as a “brother” who honestly embraced ideas of the soviets, namely the local organizations of peasants, workers, and soldiers. The problems started when he rejected the commissars based in Moscow and the rule of the Russian Communist Party. That Party spared no effort in labelling him a bandit and accusing him of antisemitism and militarism.

Makhno’s fame continued for decades after his death. Some tried to appropriate him. As Colin Darch has written, since the collapse of the Soviet Union sections of the Ukrainian right-wing have attempted to re-characterize Makhno as a Ukrainian nationalist, while downplaying his anarchist politics. More recently, Makhno’s hometown proclaimed him a local hero and erected a statue of him in one of its town squares in 2009. In 2019, Oleksandr Ishchenko revealed that the Huliaipole City Council was prepared to request the return of Makhno’s ashes from the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, as part of a campaign to attract tourists to the city, as if Makhno had become incorporated in the city’s personal brand!

Today, Adam Lent poses the question “what would Nestor Makhno do” in the current conflict.

While he would undoubtedly have fought furiously alongside the Ukrainian army to expel Putin, he would have been under no illusions about the concentrated power represented by the West. Infinitely preferable to Putin’s autocracy, of course, but still bristling with nuclear weapons, still centred on hugely powerful states, still serving the interests of enormously wealthy corporations rapidly destroying the planet.[1]

It’s important to remember Makhno’s skepticism when evaluating the reactions to the war in Ukraine of world leaders who previously aligned themselves with Putin. Donald Trump has toggled between calling Putin “pretty smart” and, later, speaking about indiscriminate attacks of the Russian army. In Europe, Dutch PVV leader Geert Wilders condemned the Russian invasion while other right-wing fans of Putin like the French Marine Le Pen, the Italian Matteo Salvini, and the Hungarian leader Viktor Orbán distanced themselves from the Russian military action last week.

Some, however, have remained consistent in their views. Thierry Baudet, the far-right political dandy and opportunist in the Dutch parliament, said that anyone who doesn’t appreciate Putin is living in “Disney World.” Ukraine, he continued, is “not a nation-state, not a country at all, but rather a conglomerate of at least two different peoples, one Russian and one anti-Russian,” and claimed that NATO provoked all of this. For him, Putin is the “leader of conservative Europe,” who was confronted with the “absurd belligerence of the EU.”

Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic, while reluctantly condemning the Russian invasion, also sent signals to Putin that he was doing so because of Western pressure and not from the bottom of his heart. In Belgrade, thousands of people are proclaiming their solidarity with Ukraine, but they are closely followed by others, who openly support their “Russian brothers.” Sad is the world in which even a simple word as “brother” becomes so politically loaded a label.

Makhno’s spirit can perhaps best be found in the position released by Russian anarchists on the war:

We, the collective of Anarchist Fighter, are by no means fans of the Ukrainian state. We have repeatedly criticized it and supported opposition to it in the past, and we have also been the target of large-scale repression… by the Ukrainian security services… And we will return to this policy in the future when the threat of Russian conquest has receded. All states are concentration camps. But what is happening now in Ukraine goes beyond this simple formula, and the principle that every anarchist should fight for the defeat of their country in war. Because this is not simply a war between two roughly equal powers over the redistribution of capital’s spheres of influence… What is happening in Ukraine now is an act of imperialist aggression: an aggression that, if successful, will lead to a decline in freedom everywhere…

Ukrainian anarchists have taken a similar position, according to Keith Preston: “In Ukraine itself, there seems to be unanimous support for the war effort among local anarchists, though there has been some initial disagreement over questions of command structure and larger loyalties. The anarchist military effort on the ground has been organized under the banner of the Resistance Committee, who themselves are under the command and control of Ukraine’s Territorial Defence Forces.”

Meanwhile, in an open letter to the Western Left from Kyiv published by Dissent Magazine, Ukrainian activist and historian Taras Bilous writes:

In recent years, I have written about the peace process and about civilian victims on both sides of the Donbas war. I tried to promote dialogue. But this has all gone up in smoke now. There will be no compromise. Putin can plan whatever he wants, but even if Russia seizes Kyiv and installs its occupational government, we will resist it. The struggle will last until Russia gets out of Ukraine and pays for all the victims and all the destruction.

Here’s my sense of the broad consensus that has emerged among those sympathetic to the plight of Ukrainians today:

- Russia is intervening aggressively in an independent state;

- The human catastrophe on a huge scale is increasing by the hour;

- Western countries are united as never before;

- Fears for the future are piling up for which there are no easy solutions;

- Other vital topics, for example climate change, are largely on hold;

- The domino effect of this war is inevitable on a much wider scale;

- At the level visible to the average public, diplomacy is failing to articulate solutions;

- Propaganda is, unfortunately and predictably, omnipresent (and not only in Moscow);

- The power-struggle of the main world players will continue for a very, very long time, even when this war is over in terms of the active use of weapons. The outcome is uncertain……

In 1999 I was invited by the Dutch party D66 to the discussion about NATO bombardments during the last stages of the war in Yugoslavia. I told them that I did not agree with the NATO attacks. They asked me what else could have been done. I told them that they, as politicians, would know better than I, but surely they could resort to blackmail, manipulation, lying, bluffing, and threats, to name just a few, to achieve their aims. It came as a surprise to the audience when I said that I was not from Serbia but from Croatia.

I am also not Ukrainian, but I deeply resent Putin’s actions in the same way that Russian and Ukrainian anarchists (and not only them) are opposing this war. Politics failed in a big way and, as always, civilians are paying the price. Other political forces must regroup, act, and forge new bonds of fraternity. In the meantime, Ukraine will remain, to use Kenneth Surin’s metaphor, a mouse trapped between two big cats. We can only hope that the mouse will distance itself from the Azov Battalion and the likes of them as well.