Cross-posted from JohnFeffer.com.

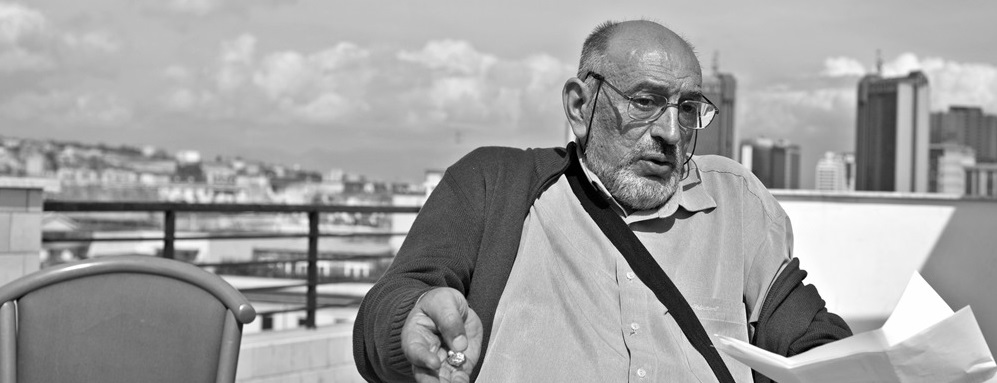

Last August 8, the great Romanian sociologist Nicolae Gheorghe passed away. He was only 66. I first met him in 1990, when he was just embarking on his project of elevating Roma issues to the highest level of European politics. Because he spoke English and had an academic background, he was often the lone Roma representative in European human rights meetings or on TV panel discussions. He worked on Roma issues at the Council of Europe, at the EU, at the UN, and for many years at the Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe.

I saw him again, and for the last time, in Budapest last May. He was very sick, in the late stages of colon cancer, and he moved with great difficulty. And yet he had pushed himself to travel from Italy to Hungary to be part of a seminar and book launch with his comrade-in-arms Andras Biro at the Central European University. The book, From Victimhood to Citizenship, is a dialogue among several people in or knowledgeable about the Roma community, and it provides an opportunity for Gheorghe to reflect on his own work and the contrasting views of others. He used his trip to Budapest to speak with a wide variety of people, including Roma students at Central European University. I managed to interview him in the lobby of his hotel on the morning before he was to return to Italy where he was staying with his sister. His day was scheduled with back-to-back meetings, and even his trip out to the airport was an opportunity for a conversation. He seemed to know that he did not have much time left, and he was determined to squeeze as many interactions as possible into his day – with old friends, new faces, and even just passing acquaintances like me.

Having absorbed the credo of cosmopolitanism from his early days in Communist circles in Romania, Gheorghe was leery of anything that smacked of nationalism. “His widest ambition for the Roma, who had no land of their own, was that they should be a ‘transnational’ people, a grand pan-European federation of men and women, who, while proper citizens of their own countries, also represented a society broader, freer and more enterprising than that of nation states,” reported The Economist in its obituary.

In the 1990s, Gheorghe saw the opportunity to realize this vision at the pan-European level. “At that time, I shifted my work from the community level to drafting documents and being oriented toward the EU: how to promote change at the commission level, which unlike the Council of Europe or the OSCE didn’t at that time have a discourse on Roma issues,” he told me last May. “I became absorbed perhaps too much in international institutions, working with the Council of Europe and EU around all these bureaucratic details. As I told you, I provided both a good and a bad role model. I was among the many people who were working and promoting change at the community level as we started in the 1990s, and then shifted toward institutions because that was the agenda. The Open Society Foundation also came in to push us to promote strategic change and institutional reform. That was my big concern. Now I criticize myself because I somehow deserted the community work to focus at the international level. I thought that operating at a higher level, at the European level, we could accomplish more in the longer term.

He acknowledged the virtues of this approach – European institutions are engaged on Roma issues in ways unimaginable 20 years ago – but he also recognized that a cosmopolitan discourse at this level met with relatively little opposition, at least rhetorically. The real challenge was to work at the local level where living conditions for Roma have not substantially improved over the last two decades and where the vestiges of earlier cosmopolitanism – from the Ottoman era or even the Communist period – have largely disappeared.

“If I were younger and had another 20 years ahead of me, I would return to community work but in a different framework,” he concluded. “We did what we could in the 1990s. But it’s a question of political generation. It was much easier at that time to penetrate into the OSCE than it is now. Now again we have a new generation of Roma politicians and activists putting the Roma issue on the agenda, and they have a new energy and vision that is all theirs. I hope that some of the Roma students that I met here in Budapest will be led by conviction to work at the community level because they believe they must make changes at that level.”

The Interview

Let’s start by talking about how your viewpoints have changed since we last talked 23 years ago.

We all expected that with the end of Communism, something that existed before and was repressed – namely, democracy – would unfold as soon as the oppressing factor disappeared. We expected that people would immediately react positively to the freedom of democratic institutions and economic enterprises. But instead we discovered how much Communism had changed people.

In my work, too, I discovered how deeply Communism changed people’s minds and their relationships. For instance, with our income-generating activities, I sincerely believed that Roma, being unemployed and excluded from the main labor market, would be successful once they were given some opportunities to organize and start something by themselves. I thought they would become entrepreneurs. I was wrong.

One of the most obvious examples of this failure with income-generating programs was the ten years of work I did in Romania and Andras Biro did with Autonomia in Hungary. We were working together. In Romania, I received half a million Deutschemarks from German churches. Biro raised another half a million dollars from the World Bank for a training program in four countries for young Roma. It was a nine-month program: three months in Budapest, three months in the United Kingdom to learn English, a couple weeks in Copenhagen at a center for developmental studies. The idea was that they would learn, they would return to their communities, and they would mobilize in the communities around income-generating activities. The income-generating activities included farming, metalwork, printing. Andras started in Hungary with pigs and potatoes and very small things. These were subsistence projects.

We wanted to be more ambitious in Romania. We tried to promote production projects. The participants would accumulate profit, reinvest some of it in the business, and distribute some of it among the participants in the program. It was supposed to function something like a cooperative. Both projects apparently failed. After the trainings, instead of going back to the community level and doing organizing, the participants were absorbed by government bureaucracies. There was a market for people with their skills, who were educated English speakers. They became bureaucrats — the pay was more attractive. Yesterday, I talked with Andras about how we would restart this project given what we have learned from this experience.

In terms of income-generating activities in Romania, most of the money was wasted. Honestly, in some cases it was pure corruption. In other cases, they didn’t know how to use the money. They thought that if they put enough money into machines, that was enough. I realized again that it was because I’d been too much influenced by the Communist model of economic development and its focus on production. I was not very clear about markets, how to market the products. We imagined that there would be a market for bricks, for metal. There were. But we didn’t really know anything about that segment of the market. We were very much obsessed with production.

The second failure was that we didn’t support individual entrepreneurship, but group entrepreneurship through associations. We wanted to tap into the solidarity of cooperatives. And the whole project was called Pakiv — and this is on the cover of the book – which means trust, confidence, and respect in Romany. To be honest and to compromise myself completely, the idea came from Max Weber and The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism and other readings in the sociology of religion. The root of the Protestant ethic is to be spiritually motivated to produce, to accumulate, and to reinvest — which is the essence of capitalism. I thought I found this ethic in the Roma community when they talk about pakiv, which is part of the whole group of concepts called Romanipen, which is a philosophical outlook toward life stressing solidarity, the sharing of resources, and being self-reliant economically. I thought that if we could connect in the Roma communities I worked with to some of these realities — imagined realities, as it turned out –, we could work like a bank.

In one village, we provided 100,000 Deutschemarks, directly, without interest. It was based on a project proposal and a contract. The idea was that they would use the money to produce, to make enough to survive, and to make enough additional to reinvest. They would create a rotating fund so that we could help others with a similar amount of money. Of course we took into account the changes in exchange rate and other technical issues. But the idea was that this solidarity between one group of Roma and another group of Roma would create a sort of market among the Roma connected to the mainstream market.

There was no enforcing mechanism. It was just moral. You just gave your word that you would give the money back, and we respected your word, because this is the Roma wisdom.

I never received one penny back. I was completely naive, coming from sociology. I knew something about some Roma communities. But I didn’t know the realities of other Roma communities. I ignored completely the context. We expected Roma to be like Protestants in a milieu rife with corruption. The model at that time was to take a lot of money from the bank and not pay it back. There were guys who bankrupted companies and made enormous amounts of money.

In Romania in general?

Yes. There was also this dismantlement of everything that was Communist-created including cooperative farms and big industries. Everything that evoked Communism, like working together in a cooperative, was rejected because they wanted to affirm individual enterprise. Sharing the revenue was redistributing according to socialist values, and they didn’t want to share. The model of success was the guy who managed to accumulate as much money for himself or herself as possible and acquire status with an expensive car, an expensive house, and so on. We went counter to the wind.

Or trust.

Or trust. But it wasn’t like that everywhere. For instance, I went to the Szekely region where there was a church-based program. We also received money from the German churches, so somehow we started communicating. In that area were farmers who followed the practice we’d tried to implement. They took money, organized their farms, and repaid their loans. It was a completely different reality. The idea that we spoke about apparently took root there, and people followed it. But it was a different culture with a different economic history. They were farmers with a patrimony of two centuries or more. Most of the Roma working in our project had no such patrimony. They’d been selling their labor. And they didn’t know what to do with money. They had no entrepreneurial skills. They imagined — and I imagined too — that if we gave them money entrepreneurial skills would just appear. And that was not the case. They wasted the money. We ended up generating personality problems: it was much more than they could mentally cope with.

Communism operated very deeply, making Roma more proletarian than they used to be. This was a people without a sense of private property. They’d even been against private property. So they were suited in that sense to the new ideology of communism. When Communism failed, liberal ideology supposedly replaced it, but there had been hundreds of years of property relations and discussions and debates behind that liberalism. And that liberalism arrived here with a shock, with “shock therapy”. It came like a recipe, and people just followed it without really being aware of its contents.

It was not a failure of liberalism. I lived in Poland for a number of years. Poland is a different model than Romania or Hungary. Apparently it’s a success in some respects. What kind of entrepreneurship did they create in order to have this success? There they had much more of a sense of solidarity, of improving society through entrepreneurship, of creating more in terms of public goods. They were also much more committed to the Catholic Church than we have been to the Orthodox Church. We approached the Orthodox Church in a very ritualistic way. The economic attitudes of Catholics are also very different from those of the Orthodox. The impact of the Catholic Church on Polish society was much deeper, for better or worse, than the impact of religion in Romania. I discovered in Poland the importance of these cultural codes and values, of morality and ethics. But in many ways I was prepared for that because of my background in sociology. I was biased from the beginning.

Slowly we realized how to be normal people. We didn’t want to be either martyrs or heroes. The martyrs of the Communist period were the dissidents, and they were also the heroes of the transition. We looked to charismatic individuals to lead us, in Romania especially. We don’t have much respect for bureaucrats, the politicians in political parties or serving in government. We like charismatic people. In Romania, the hope probably is to have another dictator like Ceausescu, with a strong hand. Instead we discovered, and I’m glad for this, that we could have a normal life, be part of the middle class. We could be mediocre and enjoy it. We could have a job, an income, go on holiday, remain anonymous — without being either martyrs or heroes.

In your essay in the book, you write about this challenge of creating an elite versus creating a group of people who return to the community to work there. In the book, you say that you created a group of people who went to work in international institutions. That’s been my experience after 23 years. I’ve met an incredible array of Roma at every level of organizations, but not much as changed at the community level. If anything, there’s a sharper divide. How can this be changed?

I provided the role model of this — in the wrong way!

But it’s what so many of us have done. I didn’t go back to my community either — not that my community needed me. We see the opportunities in the metropolis and we go there. It’s very difficult to go back once you’ve experienced that.

There’s still this debate between social democracy and liberalism about how big a state to have, a large or a small state. Communism created an enormous state in the region. The economic administration was oriented not toward the market but toward the plan. I discovered the same thing in Italy, in Western Europe, because of industrialization and the Cold War. They wanted to provide social welfare and jobs and a standard of living in order, among other things, to prove to the other camp that the Western world cared more about the wellbeing of the people than the Communists did.

The fact that people are affected by institutions is a historical fact. These institutions distribute rewards: jobs, pensions, allowances and so on. You have to enter these institutions to enjoy that. Where state institutions are reduced, the local society emerges as an actor. My recent experience is in Salerno where the reality is that the village — the local solidarity of the paese – has persisted over time through these waves of modernization. Still the family and the village type of solidarity is present there. Coming from a formerly Communist country, I was pleased and amazed to see this, to see the importance of family relations and the Church. So it is now talented young people who are returning to this reality. It’s also hopeful. Maybe the EU will become more of a union of regions and not of states. We live in a world dominated by states that promise the redistribution of wealth, and the wealth to be redistributed is becoming less and less. A major crisis may force us to think about a new actor who will appear, like the bourgeoisie in the 14th or15th century. I look for that actor but I can’t identify it.

Coming back to Roma, I was astonished by the young Roma who were able to have some success in the bureaucracy. But they often used terms in English, like “accountability,” without realizing what they mean. They had become part of the bureaucratic machinery. I had this experience as well at the OSCE. I went in as an activist, and I became an officer selling the organization. I initially said I was representing Roma organizations and I ended up learning the language of the bureaucracy and all its details. My solution was to leave that that career, despite all its advantages. I became again a private person, an activist. It was also partly because of my age. I wanted to keep this notion of a calling. I wanted to have a message. I didn’t want to make a career out of my identity. That is a risk for some people. We are disconnected from reality when we are swallowed by an apparatus that is much stronger than we are.

It’s a very similar phenomenon in the United States. Activists will come to Washington, DC. They have an identity as activists until they are absorbed into the bureaucracy. There’s an NGO bureaucracy, a government bureaucracy.

I was recently reading a collection of feminist essays, trying to learn from the feminist experience. In one of those essays was a description of the gay-lesbian movement. They started as a protest movement, provoking the establishment. But now, being recognized, they’ve been swallowed a little bit. They’ve even been used by the state apparatus as part of the war against Islam, which says, “Look at the freedom of sexual orientation here.” The protest has been channeled. In the end, you become part of the establishment and part of a bigger political game. The energy is lost. But then, probably someone else will come along with this energy and challenge.

You have talked about how Communism offered a vision of internationalism, of equality. Personally, what was it like for you to emerge from that experience in the late 1980s? As a sociologist, what it was like to observe this transition period?

I grew up in the 1950s. I absorbed the message of internationalism and cosmopolitanism. This discourse was oriented toward the national elite in Romania — because there was a dispute at that time between Romania as a national state and as a multinational state. It had to do with geopolitics, with the Soviet empire, and also the impact of the Bund, that branch of the Jewish movement, on Communism in Russia. In order to solve their problems of Jewishness, the Bund wanted to change all of society to make it possible to be a Jew without being a nation. That approach turned into dogmatic internationalism and became part of the machinery of Communism. It’s too complicated now to talk about.

Anyway, that message influenced my vision ever since I was a teenager. I went into the army first of all — to fight against NATO troops not our neighbors. That’s why I learned English in the military school: we were supposed to know NATO operations. Then came 1968-69: the Prague Spring and Ceausescu’s opposition to the Warsaw Pact intervention. Romanian Communists changed their direction after that, became much more nationalist Communists. It started actually with Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej after the Hungarian revolution in 1956. Dej opened up some distance with the Soviet Union. But Ceausescu widened this distance. Initially, it was a soft Romanian nationalism, and I was attracted to this. But then Romanian communist nationalism became more primitive, more aggressive and exclusionary. They started to exclude Jews, even those who had assimilated in Romania. They started to exclude dark-skinned musicians from TV, replacing them with white-skinned musicians.

As a sociologist, I found that if I continued to say that I was a Romanian I said it in a civic sense, like an American, not in an ethnic sense. Then in the 1970s and 1980s, Romania became more formally identified in an ethnic sense, not a civic sense. I realized that I was lying if I said I was a Romanian, knowing that I came from a family of tigane although I didn’t understand very well what that meant other than that it was connected with inferior status. I found myself in an internal conflict. Slowly, as I started to think about that, I began to open my mind. Contact with American and French students who came to Romania in the 1970s, part of the liberalization of Communism, was very important. I started to speak of myself as a Gypsy not a tigane — using the English term. It took me about 10 years to effect this change and to speak more openly about what I had previously thought of as a stigmatized identify. Even today when I use the word tigane I feel a not often pleasant emotional hollowness.

I started to describe myself as a Rom. Roma was a way to escape these emotional connotations. I started to develop a resistance to this aggressive and primitive nationalism that was constructed along ethnic and cultural lines rather than ideological lines. I was not a dissident who wanted to change the core values of Communism. Instead I tried to affirm my Roma identity. It was possible to do that at that time, to reconnect to Roma communities, to organize a Roma festival in the 1980s, to do some cultural activities. It was allowed.

To tell you frankly, there was here some kind of complicity. Along with my boss at the time, who was also Roma, we wanted to obtain official recognition of the Roma minority in the public debate in Romania just like Hungarians, Germans, Jews, Serbs, or Ukrainians. But we had to offer something in exchange. What we offered was the promise of compensation from Germany for the Roma victims of the Holocaust. We started to enter into contact with the Securitate, though not at the highest level. We managed to attract German compensation in Deutschmarks, and the Romanians were very eager to get hard currency to pay the external debt. Again, what began as a protest became something a bit different. It was somehow vicious, and I became a little bit corrupted. It also led me to create a little distance with my mentor in the late 1980s because he wanted to cooperate more with the Securitate, and I didn’t want that. When I realized the full implications of the deal, I became scared.

How did I react as a sociologist? I still wanted to find a sociological theory that could explain cosmopolitanism and humanism. Also, in the 1970s, I’d read Max Weber as an alternative to Marx, and C. Wright Mills and his critical sociology in reaction to Parsons functionalist sociology. The official sociology that I practiced when talking about the integration of rural people into modern urban society was all about how to create a consensus society on the basis of Communist ideology — instead of using a conflict theory, like Marxism, which was all about how to change society through contradiction and tension. The last years of Romanian Communism had become very oppressive, not only because of lack of food, but because this top-down consensus was very strictly imposed. Meanwhile, in the Party meetings, we talked about contradictions and dialectics. So, there was a split between the discourse and everyday life.

You can hear echoes of those times today. I dream of a civil society that is not organized around ethnic/national lines. It’s a very hot argument these days — ethnos versus demos. I favor a much more democratic society that is not ethnic-based. Romanian democracy failed partially because it was organized along ethnic lines. The Hungarians were demanding to live in a parallel society organized along ethnic lines, which was also supported in way by ethnic Romanians who had become nationalists. It’s built into our constitution and our parliament where 18 national minorities are represented, including Roma.

In the case of Roma, we continue this debate until today, and the divide has become only sharper: between Roma organizing as a national minority and as a civic democratic minority. We have looked into how to change the Romanian constitution, and what way we can do to redefine Romania not as a national state but as a civic state and to delete the corresponding article in the constitution that allows national minorities to be represented. Perhaps given the tensions of the 1990s, Iliescu sought to mobilize the support of the Hungarians. But that kind of arrangement has proven unproductive. For Roma, too, who have been fascinated with the combination of religion and ethnic nationalism that was so influential in toppling Communism. Roma opinion makers have tried to promote the idea of a Roma nation or a Roma state, and not very self-critically.

In Poland, there was a dual phenomenon related to Jews — anti-Semitism and also philo-Semitism. There was a kind of fascination within some parts of Polish society for Jews as representing something exotic, even sexy. For a period of time, it was very popular for young Poles to try to find Jewish ancestry in order to distinguish themselves and demonstrate that they were a little different. In some cases, the philo-Semitism was just as bad as the anti-Semitism — equally distorted, in other words.

You’ve met Konstanty Gebert?

Yes, I interviewed him, and he talks about this as well. We thought some years ago that this would happen with the Roma community as well, a kind of philo-Roma approach. Have you seen any of that emerge?

There is some of that in Romania. There are a lot of stories of Roma on TV, these telenovelas. And the kind of music associated with Roma is very popular in mass consumption.

Communist policy brought about big changes, sociologically speaking, in Romania by putting people from different backgrounds into the same apartment blocs and neighborhoods. These areas were associated with being Roma neighborhoods, but they were in fact very mixed, with Roma and Romanians engaged in wedding rituals according to the Roma tradition and vice versa. The kids played together. The teenagers went to the same sport clubs. The mixing was very strong. But the way to homogenize that mixed reality was to call it a Gypsy neighborhood. This kind of mixing also led to the ambiguous attitude of “we like our Roma, we don’t liketheir Roma. We like Roma musicians, we don’t like poor Roma.” The same people who love Roma music use a discourse of hate toward Roma elite. They don’t like Roma politics, but they like the tigane way of life.

I learned a lot from a book by Eva Hoffman about the Jewish experience during World War II – Shtetl — where she spoke about the responsibility of Jews in generating the kind of context that led, not to the Holocaust, but to the local vengeances that erupted with the shifting of the borders. Such a book, coming from a Jew and documenting the reality of the villages, really touched me. I read it eight years ago when I was in Warsaw. An echo of that book can be found in my own writings. I saw from what she wrote that Jews had some responsibility for what happened. I believe in this sense of shared responsibility. Instead of putting all the blame on the others, you take some of responsibility as well.

Yesterday you talked about the importance of speaking openly and to “air one’s dirty laundry” — to talk openly about the negative aspects of one’s own community. It’s a common challenge: to speak frankly but not give ammunition to one’s opponents. I went back to our interview and discovered that you said the same thing 23 years ago, that it was important to talk openly about the negative aspects of the Roma community.

I did this from the beginning. I had the experience of meeting and talking with Roma beginning in the 1970s. So I knew realities of a different sort. In the villages, we knew that there were professional thieves and they affected all the others, making the whole community more vulnerable. I spoke against racism and pogroms. But at the same time I realized that some of the victims of the wrongdoers were fellow Roma who wanted to go a different way. There was a sharp conflict between the so-called integrated Roma and those who had a deviant way of life and worked together with deviant Romanians. They stole together from the cooperative farms. But the blame was only put on the Roma. These deviants from both Roma and Romanian society despised the honest Roma as being stupid.

When the arsons against Roma houses took place in Kogălniceanu in October 1990, I regret that professor of sociology Marian Preda, who is now the dean of the faculty, came to Kogălniceanu and said it was a socio-economic issue. He said that it was not racially motivated but had to do with the behavior of Roma. It was like he was being objective as a sociologist and I was like an activist and proposing an ideological interpretation. We split over this issue. And we have remained split, to my regret. I’m not a sociologist any more. I’m an activist, which means that I am biased. This is one of the choices I had to make. Or I imagined I had to make it at that time. In the context of increasing violence against Roma, we have to stop the violence and not elaborate nice sociological interpretations. But I regret this now.

I was prepared to listen to others speaking about Roma and their own biases. I listened even though I didn’t agree with them. One of the organizations that greatly influenced me was the Project on Ethnic Relations (PER) and Livia Plaks, who just died several months ago. They were the mediators. On the other hand, I also worked with Helsinki Watch, Amnesty International, and other human rights organizations, denouncing, confronting, and eventually litigating against wrongdoers. I was very much compelled to do this. Even as we took the wrongdoers to trial, we wanted to bring back the Roma who had been expelled and promote change within the Roma community, for instance by legalizing housing and schooling or creating income-generating projects. Some of those who opposed such changes were the wrongdoers who were complicit with the police to cover up the crimes. I started to become critical of the wrongdoers because they were working against our efforts to promote change within Roma community. I took this crisis as a channel for change in the general community and for the Roma as well.

Now I am more relaxed and self-assured. Because of my age and because I don’t want to make a career, I can afford to be accused of being a racist. It is my duty to talk about these things. I didn’t have enough emotional security to talk publicly about this at the time. But in PER in 1996 I spoke about the need to bring the issue of Roma criminality to the discussion. I get very angry when I see people exploiting others, through begging or trafficking. Good friends criticized me, saying that I was generalizing, criticizing too much and feeding the chauvinism. So, it’s an open question whether airing the dirty laundry can be beneficial or counter-productive. I don’t know.

It’s controversial even today within the African American community when we have a Black president.

Obama began this discourse as a senator. Before he ran for president, he said that there are too many basketball players and musicians in the African American community — and too many pregnant teenage girls — and not enough architects or lawyers. Of course, the NAACP was not happy with this: the people of the 1960s, of the Martin Luther King, Jr. generation, were not very pleased. But we have to do this. I’m still a sociologist, and I want to preserve connections. If you want to protect a flower, you don’t destroy the soil. I’m still thinking about how to recreate the mahala – the neighborhood from Ottoman times — where people interact across ethnic boundaries. In Hungary people were together as farmers and workers. It was an asymmetrical relationship, which whites in a superior position, but they were drinking and feasting together. Then came the Gypsy Council and the rhetoric of the Gypsy elites in Budapest and the liberals. And the people discovered in the other the “Gypsy” and not the village person. I’m disturbed about this, because I saw this as well in Romania. This is my criticism toward the elite, to which I belong somehow.

Some people have told me that talking about Roma as a “problem” versus talking about inequality in general has been a strategic mistake. Poor ethnic Hungarians get resentful because they only see resources going to Roma rather than poor people in general. Andras Biro was critical of this notion. He thought it was important to talk about solutions that are Roma-identified solutions. But how do you feel?

Recently, I was looking at the book An American Dilemma by Gunnar Myrdal, which for me was important reading in the 1970s. Myrdal says that the success of the civil rights movement in the 1960s was not possible without taking into account the American credo — and that white people were dedicated to the American credo. The civil rights movement was mainly but not only a Black movement but whites could join too, and it was successful because it appealed to the core values of American society. Barack Obama is a president not because he is African American but because he has very well articulated the American credo.

What is lacking from Hungarian or Romanian society is this kind of credo. The only credo I see is the national-religious credo. The reality that appeared after Communism was to reaffirm national identity in reaction against the Soviet empire. There was liberalism and the economic market, but they were rather abstract. For the masses, there was this appeal to revive feelings of kinship and local solidarity, including the Church, which were repressed somehow under Communism. The Roma elite, to foster a sense of identity and to mobilize people, speaks of Romanipen and what is unique about Roma culture, stressing always the differences and not the commonalities. In this way, we are partly responsible for the emergence of Jobbik. I don’t want to blame us too much. We have to have a complex analysis. But somehow we helped that by stressing values without teaching the ethics of values. We speak of Romanipen but not connected to an ethic or a cultural code that compels you to do this or that — how to be smart rather than live without working, for instance. Some friends say that I am exaggerating, and I am concerned about that. I try to listen to them when they say that I am generalizing about kids being out of school or exploited. They say that this is a social phenomenon, not an ethnic one. But I say that there is an ethnic aspect to these social issues.

This is a controversial debate. But yesterday one of the things that was sorted out was how to talk with Jobbik: with whom and in what way. I would like to organize a series of talks with their leaders. We have to listen to them in the same way that I listened to people in the 1990s who justified attacks against Roma. I listened carefully. I didn’t reject their talk by saying that they were racist. I said they did wrong, and it was unacceptable. But I listened and tried to promote change. I hope that in this way, in five or ten years, Jobbik will be absorbed by the political parties and the mainstream politics. Its presence in parliament will diminish. But the discussion they started on Roma criminality in a very hot way is an opening for some changes in the Roma community.

You’ve been very honest in your discussion of some of the changes in your thinking since 1990. I want to give you another opportunity to think back to what your worldview was like in 1989-90 — not just with respect to Roma but in general — and how that has changed.

In some way, I am amazed by the continuity even the rigidity in my thinking. What I said in an interview in French in 1982 is more or less what I am saying now: about combatting ethnic nationalism, about not thinking in terms of a Romanistan. But I am much more relaxed now talking about what I thought about 20 years ago.

A major shift took place in 1997 with the prospect of Romania joining the EU. At that time, I shifted my work from the community level to drafting documents and being oriented toward the EU: how to promote change at the commission level, which unlike the Council of Europe or the OSCE didn’t at that time have a discourse on Roma issues. I became absorbed perhaps too much in international institutions, working with the Council of Europe and EU around all these bureaucratic details. As I told you, I provided both a good and a bad role model. I was among the many people who were working and promoting change at the community level as we started in the 1990s, and then shifted toward institutions because that was the agenda. The Open Society Foundation also came in to push us to promote strategic change and institutional reform. That was my big concern. Now I criticize myself because I somehow deserted the community work to focus at the international level. I thought that operating at a higher level, at the European level, we could accomplish more in the longer term.

Now, if I were younger and had another 20 years ahead of me, I would return to community work but in a different framework. We did what we could in the 1990s. But it’s a question of political generation. It was much easier at that time to penetrate into the OSCE than it is now. Now again we have a new generation of Roma politicians and activists putting the Roma issue on the agenda, and they have a new energy and vision that is all theirs. I hope that some of the Roma students that I met here in Budapest will be led by conviction to work at the community level because they believe they must make changes at that level.

I’m self-critical. At the same time I think we accomplished something. I saw how it was possible, just a few of us, to promote a change, at least at the level of language. It was the OSCE and the Council of Europe that gave me this feeling that I am an actor who can be productive. I’m proud of this. It wasn’t a matter of historic necessity, the law of history that Marxism teaches. It was because of hard work and a combination of unique circumstances. It’s a human game. This is what I try to convey to younger people who sometimes get disappointed because they can’t immediately push through the change they want. Or they don’t have access to the senior position that they want. Or they don’t manage a lot of money. They imagine they need ten millions of Euro to operate, and that’s not true. I don’t know how the frustration of educated Roma will be channeled. They are accumulating tensions generated by their unfulfilled expectations.

On the other hand I see what is happening in the camps in Italy, with young Roma who are out of school, who remain at the margins of the society where garbage piles up and prostitutes do their job and traffickers operate. They spend their time watching a lot of violence and aggression on TV. Eventually they become integrated in the informal economy and become part of organized crime. I’m afraid that there will be a radicalization of these people. I wonder if the frustrated, uneducated young guys at the grassroots will join together with radical intellectuals to create a cocktail that will explode.

We need to worry about this process of radicalization among educated and uneducated Roma youth. This is not based on evidence. Rather, it’s my nightmare, a phantasm that probably comes out of the news I’ve seen about Islamism. I first got this feeling that something could be radical and violent in 2004 when I was in Trebisov, in eastern Slovakia, on the border with Hungary. The conservative government in Slovakia made a change in the law on social welfare, reducing the social support, and there was an outburst of protests and violence directed by some Roma leaders. I went there soon after the army and the police went into the area to prepare for the advertised marches, protests, and so on. They played up this argument of Roma rioting. I was in Kosovo as well several times, in Mitrovica where there was arson in the Roma neighborhood. I observed here and there some emotions that might indicate the possible radicalization of the Roma movement.

You should travel around and verify my feelings. Part of my dialogue with Andras Biro was about that. He reminds me that I came once from Kosovo and told him to be careful of what was happening, that something bad could happen. This was before Jobbik. I’m upset less about the people at the grassroots who can slip into delinquency than about the young intellectuals who haven’t cultivated sufficient critical thinking, who take up ideologies very quickly and have adopted a kind of Roma nationalism.

It’s interesting that you say that. When we met 23 years ago, there was a young man you were talking with. He said he was in a Roma army and spoke quite radically. I couldn’t tell how serious he was being, but perhaps he was speaking in terms of self-defense. There had just been violence in Targu Mures.

At the time when people were setting Roma houses on fire, there were some Roma who said that we should set Romanian houses on fire as well. People were saying, “If they speak with fire, we respond with fire. Why do we have to be peaceful in the face of violence?” It’s good that you remind me. There were articles in the press at that time about this. An older Roma man said that he would set on fire a thousand Romanian villages. That didn’t help the situation, and I was very upset. I started to work with the police on how to contain this. I saw this among Roma in Kosovo as well.

Young people might joke about this. But I’m much more concerned when they start to articulate an ideology about a Roma nation and Roma state. A Roma nation that is civic, yes, why not. But an ethnic nation?

Budapest, May 11, 2013

Interview (1990)

[Note: I used the term “Gypsy” in this original interview summary because I was not familiar with the term “Roma” and because at that time too it was the term that Nicolae Gheorghe also used. I reproduce the original in unedited form.]

A sociologist by training, Nicolae Gheorghe is a leading figure in the Gypsy or Romany community in Romania. He has been active recently in the human rights dimension of the CSCE process (Helsinki process) in establishing Gypsies as a non-territorial minority. We spoke about the situation of Gypsies in Romania today.

There is tremendous anti-Gypsy sentiment in Romania today. Some Gypsies were responsible for this in that some are thieves and engage in black market activities. But Gheorghe noted that this was a result of poverty. He compared the situation to the Black community in the United States and made reference to the “subculture of deviance.” The main task, he thought, was to avoid continuing violence against Gypsies in Romania. To that end, he has made contact on behalf of several Gypsy organizations with the Romanian government. There had recently been a meeting of Gypsy leaders with the police.

Now, after the revolution, Gypsies have more visibility, more access to television, more opportunity for cultural activities. There is one Gypsy leader in the Parliament. Still, however, the community remains stigmatized, in part because the average Romanian still doesn’t know much about the ethnic group. Therefore, several Gypsy groups have asked the government for a cultural center, a meeting place in Bucharest where Gypsies could engage in artistic activities. The government had allocated a building but local authorities protested because the building was a monument. So, up to the moment, they have no building. Gheorghe expects that the center would be a place to show movies, acquaint Gypsies with modern technology, perhaps house a department of minority rights. Gheorghe stressed self-help. Humanitarian aid was of limited use. The West had sent much food and medicine for the Gypsy community following the revolution but this caused a lot of violence as people fought over the distribution of supplies. “I don’t think even that this kind of philanthropy was helpful.” Another result was that Romanian Gypsies, knowing that the source of the aid was in the West, headed for West Germany to get the aid at its source. Instead of such humanitarian aid, Gheorghe emphasized the need for information and technology, though he recognized that this might indeed be the bias of an intellectual.

One campaign he is now pursuing concerns the director of Romanian television. After the events of June 13-15, the director said to the press that he had been attacked by drunken Gypsies during the events. This after the police directed miners to the houses of Gypsies suspected of black market activities during the 14th and 15th. Gheorghe wants to take the director to court as an example since it would not be possible to take the entire police force to court. This strategy is not designed to punish the director but to bring his stereotypes into the open. It is not usual to bring cases of inciting to racial violence to the Romanian courts and Gheorghe realizes that he could use the assistance of a legal advisor skilled in such cases. “Maybe we will lose the case. But we will show the shortcomings of our laws, that they have nothing covering this kind of racial prejudice.” Eventually, Gheorghe envisions a Race Relations law similar to England’s.

Another important activity is the encouraging of Gypsy children to attend school. To that end, he and his colleagues have begun a program to train teachers for the Gypsy community: in Gypsy language and culture. They succeeded in getting the government to allocate certain places for Gypsy children. The problem now is to find the children: this is a new program and parents are understandably suspicious.

Other activities include a research project culminating in a reader on the situation of Gypsies throughout Eastern Europe. The various Romanian Gypsy groups have prepared many programs and are presently soliciting for funds. Gheorghe was rather cynical about the attention paid by Western organizations to the plight of Gypsies. Many representatives have visited and talked with him: but precious little has materialized in the form of money, technology or experience. I was but the latest in a long line of information-seekers.

During the Ceausescu regime, Gypsies had been mistreated by the police but nothing on the scale of Tirgu Mures. In this case of clashes between ethnic Hungarians and Romanians, Gypsies were used as scapegoats to justify police crackdown. I asked about Vatra Romaneasca. He expected an anti-Gypsy component to Romanian nationalist organizations. A secret protocol was published some time ago taking a hard line against Gypsies. Some say that this was a false document but nonetheless it may indicate something. On the other hand, Gheorghe has had only positive contacts with individual members of the organization. I asked about ethnic Hungarians. Though admitting that he might be seen as pro-Romanian, he argued that the Hungarians had sometimes made mistakes in promoting their own rights. After all, Gheorghe is anti-nationalist and some of the people in the ethnic Hungarian movement are simply old-fashioned nationalists. Their appeals for cultural rights often obscured strivings for territorial rights and some think that they have a monopoly on minority rights and “are developing a concept of a privileged minority.” The Gypsies, meanwhile, being a non-territorial minority, are only striving for cultural rights. Appeals for territorial autonomy just won’t float with the majority of Romanians and cultural pluralism must be accepted.

The two most important experiences that Westerners could share with Romanians were, in his opinion, strategies for self-help and mediation in conflict negotiations.