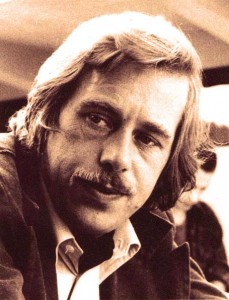

Vaclav Havel

Kim Jong Il was only the second leader that North Korea ever knew. He ruled in the shadow of his father, Kim Il Sung, the founder of North Korea. The son had none of the charisma of the father, and none of the credentials either. Kim Il Sung fought as a guerrilla against the Japanese colonizers. His battles may not have been particularly impressive – and certainly not as impressive as North Korean propaganda has made out – but he at least could point to a revolutionary record. With no battlefield experience, Kim Jong Il even felt the need to fabricate his birthplace in order to suggest an authentic revolutionary past. Official North Korean history put his place of birth as the legendary Mt. Paektu in the northern part of North Korea, when in fact he’d been born in Russia.

The younger Kim established his reputation as a film director, translating his father’s revolutionary operas into cinematic blockbusters. He always seemed more comfortable behind the camera than in front of it. He rarely made public comments. He stayed close to the military, which backed his rise to power. His first major policy as leader after his father’s death was to observe a three-year mourning period, during which his country descended into famine. He was always a half-hearted proponent of reform, backing some economic changes and then reversing himself (accepting private markets then cracking down on them, banning cell phones then encouraging their use within the elite). His chief interest, other than expanding his own huge film collection or enjoying the good life, was to preserve the power of North Korea’s ruling class. He was, at heart, a deeply conservative figure, more comfortable with the tropes of Korean nationalism than with the slogans of revolutionary communism.

Kim defied expectations in many ways. The North Korean government didn’t collapse after the elder Kim’s death in 1994. Nor did it crumble during the subsequent food crisis. Kim Jong Il managed to maintain alliances with China and Russia, coax South Korea into significant economic investments, bring North Korea into the nuclear club, and keep the United States at arm’s length at a time when other leaders (in Serbia, Iraq, and Libya) suffered regime change at the hands of U.S. forces.

But in the end, Kim Jong Il didn’t fundamentally change North Korea or offer an alternative economic or political system that could rival that of China or South Korea. He will ultimately be remembered as a transitional figure between his ruthless but transformative father and a future that has yet to be determined by his son and successor Kim Jeong Eun.

Vaclav Havel, more than perhaps anyone else of his political generation, represented the power of the dissident intellectual. A playwright and essayist, Havel brilliantly exposed the deceptions and stupidities of the communist system in Czechoslovakia. He spent time in jail. He helped nurture the small civil society that would prove so critical in 1989 in transforming not only his own country but the entire region of East-Central Europe.

Havel became president of Czechoslovakia at the end of 1989, a position that he claimed to have run for only reluctantly. However reluctant he might have been to assume the kind of political power that he had spent years deconstructing in print, he quickly became accustomed to high office. “Actually power, political power turned out to be something of an aphrodisiac for Vaclav Havel — four presidencies in two countries for 13 years,” observes his biographer John Keane. “Any obituary worth its salt will point out that if Vaclav Havel were writing honestly about Vaclav Havel it was the low point of his political career.”

Of course, even Havel’s low point was considerably better than most politicians’ high points. He effectively guided Czechoslovakia through its initial transition phase and then the “velvet divorce” that produced the Czech Republic and Slovakia. He fulfilled his promise in 2004 to bring the Czech Republic into the European Union, and today it ranks below only Slovenia among the former communist countries of the region in terms of per-capita GDP.

But when Havel tried to put his more stringent moral principles into practice as president, he discovered that the world was not quite ready for them. Along with the civil society cohort he established as his brain trust – Jiri Dienstbier as foreign minister, Alexander Vondra as advisor – he attempted to fashion a moral foreign policy. The new president invited the Dalai Lama to visit Czechoslovakia, thereby risking a severing of relations with Beijing. In January 1990, Foreign Minister Dienstbier announced that his country would no longer export arms. And Havel’s Czechoslovakia proposed a new European security order that could replace NATO.

Ultimately, the Havel team reversed itself on the arms export ban and came around to support NATO at the expense of the fledgling Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe. Havel continued to speak out on Tibet and on behalf of Chinese dissidents. But the Czech Republic also made sure to maintain formal diplomatic relations with Beijing, exchange high-level visits, and court Chinese investment.

Havel stabilized his country. But he didn’t transform politics as usual. He will be ultimately remembered more for what he did and wrote against the powerful elite than what he did when he himself was part of the powerful elite.

The Cold War generation is passing away, both those who ruled from above and those who challenged from below. It can only be hoped that the few remaining Cold War fault lines, such as the Demilitarized Zone on the Korean peninsula and that which still stubbornly separates Russia from points West, will pass away soon as well.