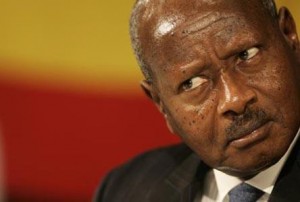

The excessive violence with which Ugandan security forces have over the last month cracked down on initially peaceful opposition protests at soaring food and fuel prices, and which last week overshadowed the inauguration of re-elected President Yoweri Museveni, is almost as puzzling as it is disturbing.

The excessive violence with which Ugandan security forces have over the last month cracked down on initially peaceful opposition protests at soaring food and fuel prices, and which last week overshadowed the inauguration of re-elected President Yoweri Museveni, is almost as puzzling as it is disturbing.

The government security forces have repeatedly used tear gas, water cannon, chemical sprays, rubber bullets, and live ammunition to disperse unarmed crowds, at first rarely numbering more than a few hundred, in towns across Uganda. At least nine protestors and bystanders, including a two-year-old child, have been killed and scores more wounded. The government has arrested protest leaders, including opposition members of parliament, on spurious charges of “disobeying lawful orders” and “illegal assembly.”

Violence flared again on May 12 when Museveni, who came to power 25 years ago at the head of a rebel army, renewed his oath of office at a lavish ceremony attended by 12 African heads of state. When they returned to Uganda’s international airport, the foreign guests had to run the gauntlet of thousands of opposition supporters who had turned out to greet their own hero —Colonel Kizza Besigye, a former comrade-in-arms of Museveni’s and once his personal physician. Besigye had just flown in from Kenya where he went for medical treatment after police had pepper-sprayed him at point-blank range — in full view of local TV cameras. To make way for the departing dignitaries, security forces cut a swath through the opposition crowds with their now-customary violence.

Excessive force has fanned the flames and shocked even government supporters. Religious and civil society leaders have denounced the state’s violence. Lawyers have staged symbolic protests at the perversion of constitutional rule. Journalists have boycotted government press conferences in protest at arbitrary beatings of reporters covering the troubles. Such political turmoil is ominous for Uganda, a country that since independence in 1962 has known many rebellions but never a peaceful transfer of power.

The turmoil also comes at a time when Uganda is looking forward to oil revenues of at least $2 billion per year. Wisely spent, these could prove the godsend that the country needs to shake off poverty and achieve national unity. In the current atmosphere, however, they seem likelier to intensify infighting among national and local political elites. In anticipation of a revenue boost, Museveni’s government has already gone on a spending spree, buying Russian jets and other military hardware worth $744 million. Expected oil wealth will increase the incentive for the 67-year-old Museveni to cling to power beyond his current term or, as some Ugandans fear, pass the leadership baton to his son, the Sandhurst- and Fort Leavenworth-trained Colonel Muhoozi Kainerugaba, whose duties as head of Uganda’s Special Forces group include guarding the country’s oilfields. Kainerugaba also led the suppression of protests in Kampala.

These are uncomfortable developments for the United States and the European Union, which provide Uganda with substantial development aid and military aid. Such support was long premised on Uganda’s supposed status as a development success story, a stable country in a volatile region, and a force for regional stability. But all that is now looking less true by the day.

Behind the Crackdown

Here’s the puzzling part. Barely two months ago, Museveni won a landslide victory in a flawed but largely peaceful election. He won 68 percent of the vote, bettering his 2006 (and even more flawed) electoral outing by nine percentage points. So why is an apparently popular president cracking down so hard on relatively modest opposition?

One likely factor is the president’s contempt for a fractious and divided opposition that ran a lackluster election campaign, relying on anti-Museveni sentiment rather than any positive vision of Uganda’s future. The opposition charged that the election was rigged, a view shared by many of their followers.

There was no evidence of outright fraud on a scale large enough materially to affect the result but, as Commonwealth observers noted, the electoral level playing field was far from level. The ruling National Resistance Movement made little effort to conceal vote-buying on a massive scale, and there is little doubt that state funds were diverted for this purpose. To many Ugandan intellectuals, the elections reflected both the corruption that has increasingly marked Museveni’s rule and the patronage networks by which he has sustained that rule.

It is also noteworthy that Museveni’s support is mainly rural in what remains an overwhelmingly agrarian society. The opposition parties have substantial support among the 15 percent of the population that is counted as urban. The capital, Kampala, returned opposition members of parliament and an independent mayor. This urban electorate, although small, is less pliable than the rural majority and able to cause Museveni much more trouble.

Altogether, then, his election victory — in a low turnout by African standards, with only 60 percent of voters participating — was not so resounding as it appeared. Museveni must know this, and it is a second factor in the repressive response to civic protest.

A third factor is that the opposition, still sore at the electoral drubbing it received, at last picked a cause that resonates with the public at large. In March, Besigye and several other presidential candidates called for protests at the election rigging. Few answered the call, and they were promptly tear-gassed. Opposition parties then switched track, calling for protests against inflation, which has risen to 11 percent in Uganda — mainly on the back of global rises in oil and food prices, although probably also boosted by the splurge in pre-election government spending. This causes considerable pain in a country where even at the best of times few families can afford to eat three meals a day.

The attempted violent repression of the protests, which began meekly enough four weeks ago with a handful of opposition leaders “walking to work” to save fuel and show solidarity with the poor, appears to have backfired. Left alone, or met half way with concessions such as temporarily lifting taxes on gasoline, the protests would likely have soon fizzled out. The aggressive government response has instead swollen and diversified them, precipitating a political crisis.

Yet it is hard to see forcible repression as merely the tactical error of a temperamentally pugnacious leader. Besigye and other political opponents have repeatedly hailed the popular uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East, and Museveni was evidently determined to nip any such protest in the bud. But his manner of doing so suggests that he feels vulnerable — and not without reason. Business and administrative elites may be co-opted with favors and preferential treatment, and rural votes won not by delivering decent services but by handing out cash and bags of sugar at election times. But when these tactics are not enough, brute force becomes the only reliable instrument for retaining control.

International Backing

Many liberal well wishers in the West saw Museveni as a new model leader when his National Resistance Army marched to power in 1986. Basil Davidson, an eminent British historian of Africa, thought he saw, in 1992, “genuine moves towards the democratization of executive power” that might inspire the whole continent. A decade later the British NGO Oxfam was still enthusing over “the rehabilitation of [Uganda’s] public services, epitomized by the creation of an increasingly visible and credible local government.”

The West’s aid architects meanwhile saw an opportunity to create a new model economy. Uganda was the first country to benefit, to the tune of around $5 billion, from debt relief under the joint International Monetary Fund and World Bank Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative. In return, Museveni grudgingly assented to donor-backed structural adjustment programs. Eschewing his leftist youth, he became an apparent convert — although, quite possibly, a convert of convenience — to free market economics and has since won consistent donor praise for “strong macroeconomic management” and pro-market policies that are credited with creating steady economic growth. Uganda continues to receive around $1.7 billion per year in Official Development Assistance, with $526 million coming last year from the United States — mostly for post-war recovery in the north.

Donor praise for Uganda has dimmed over the years as some of the early successes have paled. The government’s AIDS policy, for instance, received early plaudits, but the disease is now resurging. Evidence has also emerged of Ugandan army plundering and hooliganism in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and serious human rights abuses in northern Uganda. As Museveni increasingly appears to erode, rather than strengthen, constitutional rule, the default donor position became to emphasize the positives (open economy, increased security, fairly free press, fairly independent judiciary) while ignoring the negatives (homophobia, the general drift toward personal, autocratic rule.)

Criticism has also been muted because of Museveni’s usefulness as an ally in the war on terror and his willingness to commit peacekeeping troops to Somalia. The United States provides Uganda with logistical and communications support for ongoing operations to mop up remnants of the Lord’s Resistance Army in nearby countries. Along with Europe, the United States has also provided military training for Ugandan peacekeepers. With their combat experience in Somalia, Ugandan troops are now a seasoned force ready to address domestic insurrection, with one eye looking toward a potential future conflict with the DRC over who owns the oil below Lake Albert.

While the apparent aim of Uganda’s Somali operation is to halt the spread of extremism, they have in fact exposed Ugandans to terrorist threats: al-Shabaab carried out the July 2010 bombings in Kampala that killed more than 70 people watching the World Cup final. Security in the capital has been tightened since the atrocity, with increased surveillance in the name of anti-terrorism representing a clear threat to civil liberties. Among the dozens of arrests connected to the attack are illegal renditions from Kenya of men who are nothing more than Muslim human rights activists. In at least one such case, British and U.S. security agents reportedly interviewed a suspect who was later released without charge.

Museveni’s reaction to the June bombing was predictably bellicose. He pledged to increase Uganda’s troop deployment in Somalia while also urging the African Union to bolster the peacekeepers’ mandate to include more pro-active “peace enforcement.” The revised terms of the mandate remain unclear but the African Union force has indeed gone on the offensive, resulting in substantial military and civilian casualties. Three Ugandan soldiers have been found guilty of shooting civilians. No one has come out of the Somali conflict a winner, except perhaps Museveni himself, who has deftly used his position to receive aid, buttress his own rule, while still frequently launching tirades against Western meddling in African affairs.

Out of the Morass?

The problems that Uganda presents make it hard to share the State Department’s upbeat assessment of the country as playing “a key and growing role in advancing regional peace and security.” Domestically, economic liberalization has not brought political liberalism so much as authoritarian populism, richly laced with nepotism and cronyism. And if Museveni is looking increasingly autocratic at home, the military adventure in Somalia is looking no more likely to advance regional peace and security than the previous adventure in the DRC.

Yet it is also hard to see a way out of the morass. Museveni must make concessions to an opposition he despises in order to stave off an economic crisis. Businesses have already started grinding to a halt as a result of the increasingly violent stand-offs. There are reports that he is trying to placate his foes by offering cabinet posts to selected individuals. This strategy may work, as the opposition is only precariously united, shows no sign of having an agreed or coherent strategy, and includes many ambitious would-be leaders. The great majority of Ugandans want a return to peace, and even the most vigorous protestors need a break. “Riots only last a couple of hours in Uganda” said Kalundi Serumaga, a well known radio host and columnist, “because people have to go and find their next meal.”

But a short-term political deal, though necessary, will not solve the underlying problems. The best hope is that Museveni will abandon any thought of continuing to rule, directly or by proxy, after his current term ends in 2016, and that he will meanwhile adopt a more open and inclusive approach to government, allowing parliament more than a rubber-stamp role. But this seems unlikely to happen, and Western influence seems unlikely to help. Donors have poured millions of dollars over the last five years into programs designed to “strengthen democracy” with few tangible results.

European donors may well trim the general budget support that they (unlike the United States) give directly to Museveni’s government. But they will do so only reluctantly, unwilling to lose influence over a country that is growing more important in a region reconfigured by the independence of Southern Sudan, and at a time, moreover, of intense Western anxiety about loss of influence to China. Commercial interests will also increasingly muddy diplomatic relations as the exploration and exploitation of the region’s oil and mineral wealth intensifies.

Generic conclusions are easier to draw than specific policy prescriptions. Embroiling Uganda in Somalia as an ally in the war on terror almost certainly nudged the country closer to what some Ugandan commentators describe as an “elected military dictatorship.” Bilateral development aid, with its inherent patron-client relationships and implicit purchase of diplomatic leverage, is, or should become, an anachronism in a more globally democratic 21st century. Aid would be better channeled through fully independent and democratically governed multilateral institutions and development banks. Even then, it is well nigh impossible to separate aid for people from support for their rulers. International trade would better serve developing countries and intellectual property rights regimes that encourage rather than inhibit or prohibit technology transfer and the protection and fostering of infant industries. Finally is the enormous difficulty of establishing the kind of democratic institutions that evolved over many generations in Europe and America in a poor, predominantly rural society. A glimmer of hope here is the role that civil society has played in Uganda over the last fortnight in calling for dialogue and mutual respect. But that predominantly urban civil society needs to find its own path, rather than being propelled by foreign diplomats and aid.

As a practical step, Western powers should do everything possible to encourage and support the nascent East African Community (EAC), (comprising Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi. Closer political integration might be more stabilizing for the whole region than looking for nation-states to fix to the problems of poor, agrarian societies with horrible colonial histories and artificial boundaries.

While it is no regional panacea, the EAC is nonetheless well worth backing. The problems are immense and tensions and spats have marred progress, but achievements like the common market established last year are significant. The regional market is big enough to foster development of local industries. The community is already borrowing from the African Development Bank, as a bloc, for oil and gas infrastructure development. Joint responsibilities and ventures of this kind, and the economic benefits to members of the common market, may encourage convergence around minimum governance standards and encourage more responsible national leadership.

Museveni himself has long been a staunch advocate of regional integration and ultimate federation. If he relaxes his grip on Uganda now, and prepares to leave power responsibly in 2016, he may yet be remembered by history as a great architect of federation. If he does not relax his grip and prepare to go, he will likely wreck the integration prospects by persuading Uganda’s neighbors that the country is in for another prolonged period of lunacy.