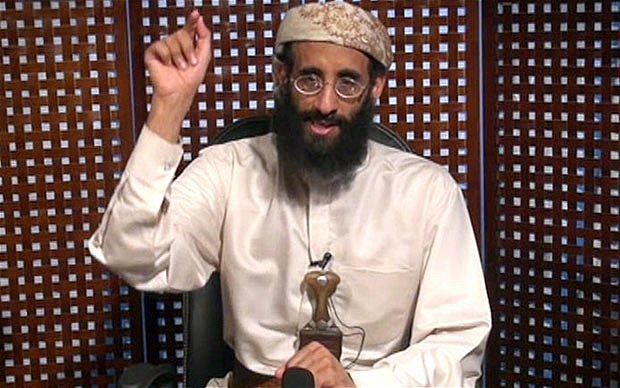

Anwar al-Awlaki, the first American citizen killed without trial by the U.S. government in decades, is arguably the most influential and beloved teacher of Islam and, later, jihadist in recent years. In the New York Times magazine, Scott Shane writes about both his 53-CD series on the life of Muhammad and his domination of YouTube, in one of which he explains why Muslims must kill Americans. He was a favorite of Nidal Hassan, the Fort Hood shooter, and Umar Farouk Abulmutallab, would-be airline bomber.

But if both mainstream and extremist Muslims knew the true Awlaki, their esteem for him might not have been so high. Before we get ahead of ourselves, from Shane’s piece:

In fact, Awlaki’s pronouncements seem to carry greater authority today than when he was living, because America killed him. On Sept. 30, 2011, the day that Obama announced Awlaki’s death, many Islamic websites attached the word ‘‘martyrdom’’ to this news. … [His] rich afterlife on the web raises disturbing questions: Is Awlaki as dangerous — perhaps even more dangerous — dead than alive?

Shane also asks:

Was there a way to undermine his message without giving it the gloss of martyrdom?

He concludes there was and it lies in Awlaki’s Achilles heel — his practice of meeting American prostitutes in motels. One of the main factors leading to Awlaki’s radicalization was U.S. government surveillance of him, which included the FBI following him to his solicitations. Shane again:

The reasons for Awlaki’s eventual departure from the United States, and for the steady hardening of his message that followed, have long been misunderstood. For years, anyone who studied his story assumed that he judged life in America as a Muslim leader to be no longer tenable.

However, in 2002, what he said to his brother Ammar suggests otherwise.

‘He said, ‘Something happened last night that made me reconsider my stay here in the States,’ ’’ Ammar recalled. ‘‘ ‘I was told that the F.B.I. has a file on me, and this file could destroy my life. I’m now rethinking my options, and one of them might be as drastic as leaving the States.’ ’’

Awlaki did not tell his admiring younger brother what was in the file. But a document from the 9/11 Commission records at the National Archives, declassified at my request, shows that a few days after Ammar’s arrival, the manager of an escort service called Awlaki to warn him that he had been interviewed by Wade Ammerman, an F.B.I. agent, who had asked about the imam’s visits to prostitutes. It was clear from Ammerman’s questions that the F.B.I. knew everything.

In other words

Awlaki’s panic, his sudden agitation about the course of his life, does not appear to have been triggered by American hostility to Muslims. Rather, he seems to have realized that his own un-Islamic behavior had put his career success and family comity at risk [as well as] the moral authority he brought to public arguments over the war in Afghanistan or the dubious roundup of Muslim men.

Shane offers two alternate histories. The first:

What if the F.B.I., recognizing Awlaki’s influence and value as a mediator with the Muslim community, had assured him that there was no plan to use the prostitution evidence to charge or embarrass him? What if he had resumed his life in Washington and continued to grow into an important public figure? Might he have become a responsible leader, a voice in the debates over the wars in Muslim countries, the wisdom of drone strikes, the fate of Guantánamo?

Failing that, the second:

A more outlandish idea was raised immediately after Awlaki’s death by Ed Husain, a former British militant who recounts his journey into and out of extremism in his memoir, ‘‘The Islamist.’’ Husain suggested then, and believes now, that a better approach might have been a careful, high-profile public release of the prostitution files on Awlaki. ‘‘He was an imam when he was up to these shenanigans,’’ Husain told me. ‘‘Exposing that, I think, would have discredited him and more important undermined the message — that they are these high and mighty, pious, believing brothers who are declaring jihad on the West. Expose them for what they are.’’

In any event, Awlaki didn’t deserve death by drone strike. Nor did, a couple of years later, his 16-year-old son Abdulrahman.