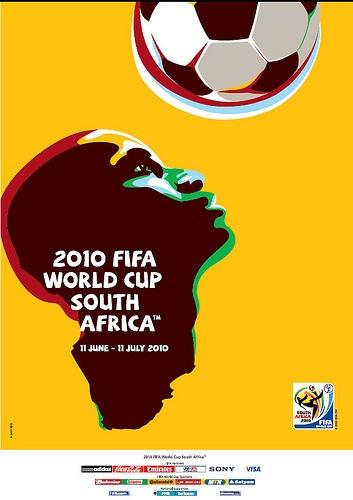

The World Cup is coming to Africa for the first time. The Cup will provide many opportunities to Africa and Africans; for example, Africa will have an opportunity to shine in the spotlight of world attention and forge a new post-post-colonial identity in the 21st century. The Cup also provides an opportunity for me to reflect on how my own identity has been caught up with Africa and soccer.

The World Cup is coming to Africa for the first time. The Cup will provide many opportunities to Africa and Africans; for example, Africa will have an opportunity to shine in the spotlight of world attention and forge a new post-post-colonial identity in the 21st century. The Cup also provides an opportunity for me to reflect on how my own identity has been caught up with Africa and soccer.

In 2002, I was in South Africa as a student at the University of Cape Town. I remember the pride we all felt at the progress of the Sengalese team. It was my first truly pan-African moment. There we were, students from all over Africa, Europe, and America, some of us members of the African diaspora, some not. But we all felt a deep sense of pride about a team from Africa holding its own against the best squads in the world. I also remember stepping outside our dorm during halftime to make a food run. The streets of Cape Town were completely empty. We were all tuned into the same moment.

My earliest World Cup memory, however, is from 1994. My father, a former professional soccer player in Nigeria, had just given up one of the great ambitions of his life — to turn his sons into great soccer players — after we had decided to dedicate ourselves to basketball instead. My brothers and I had never sat through an entire soccer game. We found the game boring, and we thought that it lacked the flash of basketball. Yet my disciplinarian father enticed us to watch the World Cup with a prize he had never offered before: He would allow us to stay up late to watch the games in real time. Initially drawn to the novelty of watching TV after our bedtime, we soon fell for the Nigerian squad, the Super Eagles, and for the first time, we felt a tangible connection to our Nigerian heritage.

I am a first-generation American who grew up in Utah. That statement alone should provide a sense of my biography; there weren’t many people like me around. Although I was a happy in school and had great friends, I struggled to form a sense of identity. Initially, I found my identity in sports. I was a big fan of the Utah Jazz and I especially admired their star power forward, Karl Malone. I studied each of his interviews and attempted to model myself after him — after all, he was a popular black man in Utah, perhaps the only popular black man in Utah, and I hoped to become popular myself. Soon after I became obsessed with Hakeem Olajuwon of the Houston Rockets. Olajuwon convinced me that the world would accept me — an American of Nigerian extraction — as long as I worked hard and excelled.

Yet I never thought of myself as a Nigerian until I saw the Super Eagles playing on television in that 1994 World Cup. As I heard the commentators stumbling over their names, I heard echoes of my teachers and friends stumbling over my name, and I instantly felt a kinship with them. And most importantly, the Super Eagles had style. They played with reckless swagger, and they always seemed convinced that they were the best players on the pitch. I derived a great deal of confidence from their performance.

The 2010 World Cup will start in a few short days in South Africa. In many ways, the Cup presents an opportunity for South Africa — and Africa as a whole — to begin to resolve its own identity issues. South Africa is a place with multiple identities.

In the past 20 years, South Africa has been an apartheid state, a bastion of democracy and reconciliation, an oasis of economic opportunity, a country led by AIDS deniers, and, of late, a country that features a widening economic gap between rich and poor. These narratives about South Africa are coming to the fore as South Africa takes its place at the center of the world stage. The Cup will shine a light on sociopolitical issues that have been percolating for a long while and perhaps force the leadership of the country to attend to the problems of the poor. There is something to be said for the embarrassment factor — as long as South Africa doesn’t resort to mere cosmetic surgery and instead seriously works to reduce extreme poverty in the country.

The Cup will also provide an opportunity for people from every part of the globe to experience African hospitality for the first time. And, like a 12-year-old in Utah almost 20 years ago or a 20-year-old in South Africa at the beginning of this century, many will fall in love with a particular squad, for a particular reason.

I, for one, know whom I’ll be rooting for this year. I’ll be rooting for South Africa.

And I’m not just talking about the soccer team.